![]()

PART I

BEFORE ELLIS ISLAND

![]()

1

EARLY YEARS

Howard Andrew Knox was born on March 7, 1885, in Romeo, Michigan, just thirty-two miles north of the center of Detroit in northwestern Macomb County. According to the 1880 census of the United States, Romeo was then a village with just 1,629 inhabitants. Macomb County today is part of the Detroit metropolitan area, but Romeo has retained its identity and character as a village. At the time of the 2000 census the population of Romeo still numbered fewer than four thousand, and many of its nineteenth-century mansions and timber buildings survive.

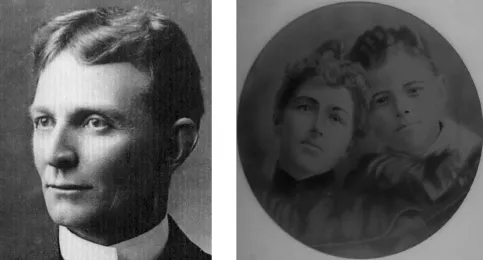

Knox was the only child of Howard Reuben Knox and Jennie Mahaffy Knox (see figure 1.1). His father had been born in 1855 to Reuben and Emerette Knox in the town of Saybrook in Ashtabula County, Ohio, and worked as a traveling salesman. His mother had been born in 1863 to Irish immigrants, Andrew and Anna Mahaffy. Although Jennie had been born in Romeo, she was sent to Ireland to be brought up by other members of her family. She returned to the United States in her early teens to keep house for her father on his farm in Romeo when Andrew and Anna Mahaffy separated.

Howard Reuben Knox and Jennie Mahaffy were married in Ashtabula, Ohio, on July 14, 1879, and Howard moved in with his wife and father-in-law to help them work their farm. However, after their son, Howard Andrew, arrived, the family (grandfather, parents, and grandson) moved back to Ashtabula. This was a town with more than five thousand inhabitants on the southern shore of Lake Erie, about fifty miles northeast of Cleveland. Ashtabula was already becoming a thriving port, handling mainly coal and ore. Indeed, the harbor district in Ashtabula, where the family found a house, was so well known that mail could be addressed simply to “Harbor, Ohio.”

1.1 Howard Reuben Knox; Jennie Mahaffy Knox with Howard Andrew Knox. Both photographs probably date to about 1890. (Courtesy the late Carolyn Knox Whaley)

Howard Andrew Knox’s parents separated when his father moved to Virginia to set up a business investing in tobacco futures. Although Jennie and Howard Reuben subsequently divorced, the latter kept an office in Ashtabula for many years, and Jennie and Howard Andrew remained in touch with Howard Reuben until he died in the 1920s. Even so, it is unlikely that he had much of an influence on his son’s development. In contrast, Howard Andrew Knox had a close relationship with his mother that endured until her own death in 1929. In 1894, when he was just nine years old, Howard Andrew Knox acquired a stepfather, Leander Blackwell, who was to have a decisive influence upon the boy’s choice of career.

LEANDER BLACKWELL

Leander Blackwell was born in December 1867 in the town of Blackwell Station, Missouri. The town is known simply as Blackwell today and is located in St. Francois County, about fifty miles southwest of the center of St. Louis. Leander’s great-grandfather, Jeremiah Blackwell, had been born in Hopewell, New Jersey, and had fought for the United States in the War of 1812 against Great Britain and its colonies. After the war he had obtained a large grant of land in the Territory of Missouri, and the settlement that he established there was subsequently named Blackwell Station in his honor. His children intermarried with the families of other settlers and over time became prosperous (Hoelzel and Hoelzel 2000:12).

Aquilla Blackwell, Jeremiah’s grandson, was born in 1844 and at first helped his father work his farm near Blackwell Station. After the Civil War Aquilla married Dolly Coleman. Following the birth of their first child, Aquilla Blackwell cleared two hundred acres of forest at Valle in neighboring Jefferson County in order to establish his own farm. According to an account published in 1888, “he now has about 300 acres in cultivation and about eleven miles of fence, making one of the best farms in Jefferson County. In all, he has about 960 acres, about 400 of which are in St. Francois County. Besides this he has considerable property in Blackwell’s Station” (History of Franklin 1970:858). He also became a judge of the county court and “rode the circuit,” presiding at various locations to hear lawsuits and other complaints or disputes.

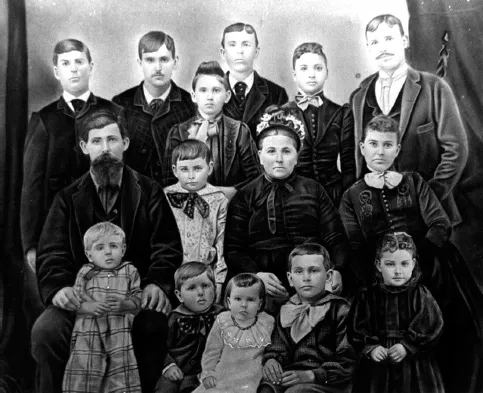

Aquilla and Dolly Blackwell had fourteen children, of whom Leander was the oldest. The image in figure 1.2, which is taken from a tintype (ferrotype) dating from 1890, shows Aquilla and Dolly Blackwell with thirteen of their offspring. After initially working on the family farm, Leander set up as a local trader in 1888. However, in 1891 he enrolled at the Missouri Medical College (now the Washington University School of Medicine) in St. Louis. He enlisted Samuel Fulton Thurman as his preceptor (mentor for practical clinical training). Thurman was a general physician in the French colonial town of Ste. Genevieve, about fifty-five miles south of St. Louis, who had graduated from the Kentucky School of Medicine in Louisville only two years earlier. Blackwell completed the first two years of the four-year program at the Missouri Medical College, but in 1893 he transferred to the Jefferson Medical College (now part of Thomas Jefferson University) in Philadelphia, which also had a four-year program.

How Blackwell met Jennie Mahaffy Knox is not known, but by March 1894 they were planning to marry once he had taken his examinations. Blackwell did not subsequently graduate from the Jefferson Medical College. Nevertheless, completing three years of medical training would have entitled him to obtain a license by taking a state medical examination, even though he did not hold a medical degree. (Shortly afterward, in July 1894, the law in Pennsylvania was amended so that only graduates of recognized medical colleges could apply for examination by the state medical board. See Polk’s Medical Register 1902:1648.)

That Blackwell actually passed this examination cannot be conclusively verified, because the examination records of the Pennsylvania Board of Medicine were destroyed in a fire in 1994. Nevertheless, he later styled himself “Dr.,” he was considered to merit an obituary in the Journal of the American Medical Association (“Leander Blackwell, M.D.” 1904), and he was subsequently listed in the Directory of Deceased American Physicians (Hafner 1993:132). Indeed, it is quite clear from Howard Knox’s personal correspondence that Blackwell’s interest in medicine was a primary factor that determined his stepson’s subsequent choice of profession.

1.2 The family of Aquilla and Dolly Blackwell, 1890. Leander Blackwell is at the top right. (Courtesy Elizabeth Mueller and Mary Myers)

Leander Blackwell married Jennie Mahaffy Knox in May 1894, and they set up a home in Cleveland. A newspaper report after Blackwell’s death claimed that he practiced medicine in Cleveland, but this appears not to be correct. He is not listed as a physician in any local directory from the time, and he made no mention of any medical practice in his personal correspondence. There is, in fact, no evidence that Blackwell ever went on to practice medicine at all. He is not listed in the relevant editions of Polk’s Medical Register, and his entry in the Directory of Deceased American Physicians describes him simply as an “allopath” (that is, a practitioner of conventional medicine, as opposed to a homeopath, a practitioner of homeopathic medicine) but lists no specific licenses or practices.

Indeed, although Blackwell was sufficiently motivated to undertake formal training and qualification in medicine, he seems to have always intended that his career would lie elsewhere. He was, one must remember, the oldest son of one of Missouri’s established families, yet he sought to marry a divorced woman who was four years his senior and who had a nine-year-old child. It is quite probable that his family was willing to approve of this marriage and to continue to support him financially only if he secured professional status—and a potential fallback if his career plans did not work out—by qualifying as a physician.

During this time relatives in Ashtabula had looked after Howard Knox, but in July Jennie Blackwell took him to spend the summer on a farm that her mother had acquired in Romeo, and Jennie brought her father to live with her and her new husband in Cleveland. In August she spent a week dealing with legal issues in West Boylston, a town of about three thousand inhabitants in Worcester County, Massachusetts. The town had been chosen as the site for a new reservoir to supply the expanding city of Boston, and many of West Boylston’s residents were displaced. Jennie Blackwell had owned property there, and she seems to have acquired a farm nearby as part of the compensation settlement. Soon afterward she brought her father, husband, and son to live on the farm.

AT SCHOOL IN WILLIMANTIC

The family lived in West Boylston for several years but in 1899 moved to another farm on Babcock Hill outside Willimantic in Windham County, Connecticut. Figure 1.3 shows Leander and Jennie Blackwell around this time. (As I will explain in a moment, that they are pictured on a horse-drawn sled is especially poignant.) The move proved to be highly fortuitous for Howard, who was now fourteen. Willimantic was a thriving manufacturing center with about nine thousand inhabitants and was part of the town of Windham, twenty-five miles or so east of Hartford. The local public high school had been created in 1888 with the merger of two existing schools, and a new school building had been opened in April 1897.

As Tom Beardsley, a local historian, said of the building in an article that ran in the Wil limantic Chronicle in 2000, “its fine Italian Renaissance style attracted favorable comment from all visitors to the city. The new principal, S. Hale Baker (1895–1900), established a school newspaper and started an ivy-planting day to adorn the new school’s walls. He also established a tree-planting program, and formed the Windham Athletic Association in the school” (14). Knox settled in well at his new school: the report that he received from the principal in June 1900 showed his grades as either H (honor work) or A (excellent) in most subjects.

1.3 Leander and Jennie Blackwell, ca. 1899 (Courtesy the late Carolyn Knox Whaley)

The new school’s second principal, Arthur Everett Petersen, replaced Baker that summer. Beardsley commented that Petersen

laid down strict academic standards. He had an excellent record in getting students into colleges and universities across the nation. He was a history and civics teacher, who believed in education beyond textbooks. Petersen formed the school improvement society, Die Besserung, to promote culture among the students, and to encourage them to decorate their schoolrooms and corridors with pictures, statues and busts of famous men. Members of Die Besserung also entered into debating contests with the high schools of Putnam, Rockville, Stafford Springs, and Danielson.

(14)

Arthur Petersen and Leander Blackwell appear to have been the major influences on the young Howard Knox. When he graduated from high school in 1903, Petersen had inspired his student to aim for a university education, while Blackwell had inspired the young Knox to take up medicine as a career. Blackwell and some of his relatives were also leading members of the Masonic Lodge in his home town, and Knox probably joined the Masons as a young man.

After high school Knox entered the medical school at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. (In those days the M.D. was a first degree, not a postgraduate qualification.) Like many other students Knox suffered an initial bout of homesickness, but within a month his attitude was more positive. On October 23 he wrote to his mother: “Life is just beginning to be worth living here. I am getting acquainted and coming along pretty good in my studies. This ain’t half so slow a place as I thought it was.” By November 20 he was positively enthusiastic: “I now have all the signs, passwords, and grips etc. of the frat and have been down there studying the skeleton today. You couldn’t hire me to leave Dartmouth now.” (The “frat” in question was the Alpha Chapter of the Alpha Kappa Kappa fraternity, founded in 1888.) Knox came home for the Christmas holiday and returned to Dartmouth in the New Year, but his studies were soon interrupted.

A TRAGIC ACCIDENT?

The family’s farm was located on Babcock Hill Road, which linked the towns of Lebanon and Windham and overlooked the Willimantic River valley. The house was about two miles from both of the two railroad depots in South Windham, one serving the Hartford-Providence line, the other serving the Central Vermont line. The two lines converged at Willimantic station, about three miles to the north. The engineers on the two lines often raced each other to Willimantic, and accidents were common.

In the early morning of January 15, 1904, Leander Blackwell was killed by a freight train while trying to cross the Central Vermont line in his horse-drawn sled. The accident was duly reported later that day in graphic detail on the front page of the Willimantic Chronicle:

Mr. Blackwell had been to the Consolidated road depot to leave milk to go to Providence on the train that leaves here at 6:15 a.m. From there he drove back to the Central Vermont depot, where he loaded his two-horse sled with several bags of grain from a box car which stood on a side track. After loading his sled he drove out from the rear of the station, and followed along beside the track, and then turned upon the highway and started to cross the tracks just as the freight came along. No one saw the accident except the engineer, although there were several South Windham people, who were on their way to work, but all were some distance from the crossing. Some say they did not hear the engine whistle, and others say the whistle blew several times for the crossing. All agreed that they heard the train and that it was going at a high rate of speed. The engineer said that he saw the team on the crossing, but he was so close to it that he could not stop his train. He said that the man saw the train and whipped his horses and tried to get across in front of it, but the train was too close and the engine struck the sled just back of the horses, killing the man and one horse. The sled was completely demolished, and pieces were scattered all about the crossing, and the force was so great that the off horse was cut loose from the sled and pushed to one side, the only injury being shown a cut on its head. The other horse was thrown in front of the engine and disembowelled, and dragged up the track a short distance and thrown upon a sidetrack.

The Chronicle’s reporter speculated about the cause of the accident. An electric bell was supposed to ring at the crossing to warn of approaching trains, but this was faint and often did not ring at all. Workers at the railroad depot said that Blackwell had been careless when driving around the railroad. One suggested that he had mistaken the train’s whistle for that of another train passing on the other railroad. Although Blackwell’s death was generally regarded as a tragic accident, Knox had written to his mother on November 25: “Don’t worry about the change which has take...