![]()

PART 1

The “Pénétration Pacifique” of the Algerian Sahara, 1844–52

Solitudinem faciunt pacem appellant. [They make a desert and call it peace.]

—Tacitus

Il a fait de notre pays un désert. [He made our land a desert.]

—French translation of Kabyle poem, recorded in the 1850s

![]()

[1]

THE PEACEFUL EXPANSION OF TOTAL CONQUEST

France’s expansion into the Algerian Sahara began with war. On 14 March 1844 a column of three thousand French soldiers arrived at Biskra, a strategic oasis located in the Ziban region at the desert’s edge, southeast of the city of Constantine.1 The son of Louis-Philippe, the duc d’Aumale, led the troops. The young, twenty-two-year-old general still glowed from his victory the previous year against Emir Abdelkader, the famous “prise de la smala” (16 May 1843), and he was confident that this expedition to the faraway Sahara would bring further glory and add imperial luster to the family name. The Orléans family, this fragile “dynasty without a past,” sought lasting legitimacy, and military conquest in a far-off and exotic desert land was one way to increase public favor and blur the fact that it owed its political life to the Parisian barricades that had toppled the Bourbon Restoration in 1830.2 Less important in this grand scheme of French politics—but significant to the struggle against Abdelkader—were Aumale’s military goals. Although a remote oasis, Biskra afforded Aumale the chance to kill two birds with one stone. He would oust Muhammad Seghir (Muhammad al-Saghir ibn Ahmad), whom Abdelkader had named his French governor, or khalifa (qalīfa) for the Ziban and reinstall the Ben Ganah family, the region’s traditional rulers, who had rallied in support of France.3 With the Ziban placed under allied rule, Aumale hoped to return north through the Aurès Mountains and seek the main prize, Constantine’s Ahmed Bey. The capture of this fugitive leader—who had inflicted the humiliating 1836 defeat on General Clauzel and who stubbornly continued to resist after the fall of Constantine in 1837—would be a major victory and sure to be warmly hailed in the capital.4

Fortune accompanied the young general. Although the itinerary posed many dangers (including a perilous traversal of the Aurès Mountains through the gorge of al-Kantara and dangerously stretched supply lines), the first stage of the operation went in Aumale’s favor. When the inhabitants of Biskra saw the large force outside their doors, factions sympathetic to the Ben Ganahs won the day, and they sent delegations bearing dates to meet the French. When French forces entered the oasis, they did so without firing a shot. Buoyed by his success, Aumale negotiated the submission of Biskra and left behind a small detachment of “tirailleurs indigènes,” supplemented by 275 of Muhammad Seghir’s men, who had changed sides. Under the command of a Ben Ganah leader (supervised by two French officers), the garrison received orders to hold this far-off post. Aumale boasted that the conquest was “entirely peaceful.”5

Governor-General Bugeaud, Aumale’s superior and the architect of the Saharan expansion, was exuberant. His skillful maneuvering around recalcitrant officials in Paris had paid off. The southeastern region appeared well on its way to submission and the outpost at Biskra promised to extend French influence well into the Sahara and beyond. As Bugeaud reported to the minister of war, “The submission of the Ziban is an event much more important than one might think in France. It was detrimental for our overall domination to have left the flag of Abdelkader fly there for so long; this gave people a weak impression of our power, and it was a permanent danger for our security in the province of Constantine.” Bugeaud promised other advantages as well: “Economically speaking, it is also very important; our tax resources will increase, and our commerce sees the doors of the desert open before it.”6

All of this had been achieved with little bloodshed. In Bugeaud’s view, the hostages taken from among Biskri families guaranteed that their kin would offer no opposition in the future. The painless occupation would be just as easy on the government’s coffers. The rich palm gardens of the Ziban represented a sizable tax base, and the mission had already taken 150,000 francs in forced contributions and confiscations. Moreover, experimenting in indirect rule, Aumale decided to install a hybrid occupation force. Overseen by an Arabic-speaking French officer (who were known as “Africains”), locally recruited soldiers ensured order, while Ahmed ben Ganah remained the actual head of the region with his traditional title of Shaykh al-Arab. As Aumale boasted, “Things were organized in a manner that allow us to give the Cheikh el-Arab the authority necessary for him to rule with confidence, albeit in a manner that our commandant can exercise continual surveillance over his actions.”7 The Ben Ganahs could deal with complex local issues the French little understood, while the French officer ensured that he ruled according to French interests. Aumale did not need to point out that this occupation method would pay for itself and require a minimum of French manpower.

When the mission’s reports and letters appeared in the official Moniteur universel, Bugeaud happily took this as a sign of the government’s satisfaction. He had undertaken the operation with little communication from Paris, and his bold decision to lead the move southward with the king’s son was vindicated in terms of the successful and easy victory. Attaching the Orléans name to these triumphs helped his political standing with the monarchy, a move that Bugeaud had carefully calculated. With the French flag planted peacefully at the entrance to the desert by Louis-Philippe’s son, Bugeaud’s claims that his leadership in Algeria had brought progress—indeed, that the costly war had rounded a corner in the Sahara—received a sympathetic hearing at the Tuileries Palace. With improved tactics and a newfound ability to project power to the interior of Algeria, Bugeaud gave substance to his claims that the hard-fought battles for Algeria’s northern lands were a thing of the past. Outflanked to the south, the remaining Algerian rebels would recognize the futility of resistance and lay down their arms. A new era of peace lay ahead for the Algerian colony.

THE RESTRICTED OCCUPATION AND THE SAHARA

It was a turn of events that frustrated officials in the capital welcomed. The 1830s had not gone well. Vague as they were, Louis-Philippe’s promises of 1834, when he decided to stay in Algeria in a limited occupation, remained unrealized a decade later. Criticism mounted that the government lacked clear vision. Already in 1840, when the restricted occupation was abandoned, one deputy disparaged the conquest’s first decade by saying, “we had neither a plan nor a system.”8 The government could not articulate its goals in Algeria. The claims of some, that the territories might fit into revived mercantilist schemes, seemed unfounded, and many observers doubted that France needed to embark upon another “New France” settler colony, the memory of the North American debacle still not forgotten.

Notwithstanding the critics, there was a system and plan for Algeria. The ordinance of 22 July 1834 gave the colony an official name—the unwieldy Possessions françaises du Nord de l’Afrique—and a system of rule through royal ordinances. It organized administration under the auspices of the minister of war, who appointed Algeria’s governor-general.9 The governor-general of Algeria occupied a powerful position, overseeing authoritarian political institutions. He controlled combat forces and stood at the head of a military-dominated bureaucracy responsible for finances, justice, commerce, and the police. Although answering to the government in Paris, the governor-general influenced policy-making for Algeria, and he could rule by emergency decree.10 The independence, power, and visibility of this office made it one of the most attractive commands in the French army.

The 1834 plan limited French control to coastal cities (such as Bône, Bougie, Algiers, and Oran), and after 1837 the inland eastern capital of Constantine was added. The focus was on Algeria’s northern lands, known locally as the Tell, where a Mediterranean climate provided sufficient rainfall for settled agriculture.11 This was first divided into various beyliks or agaliks, led by traditional elites and former Ottoman leaders who recognized French sovereignty, or by French-appointed Algerian notables who answered directly to the governor-general.12 The Treaty of Tafna (30 May 1837) recognized Abdelkader’s authority over the western Oran region and ceded him control of the territory south of Algiers. The Sahara did not figure in these plans. To the extent they thought about the dry southern lands known as the Sahara (al-Ṣaḥrā), which included both the desert and the southern steppes and high plains (High Plateaux), planners attached them to the Tell. In the Sahara a dry climate dictated a pastoral life and, where possible, irrigated cultivation of date palms, neither of which promised much to the French.

In many ways the restricted occupation continued traditional patterns of Mediterranean colonization exemplified by the seaport colony.13 Such “gateways” linked the sea and the interior, serving as points of contact and exchange. Although colonial planners did not draw direct inspiration from this example (unlike the Roman one),14 they hoped that the restricted occupation—the first experiment with a “pénétration pacifique” in Algeria—would allow France to maintain an unobtrusive and low-cost presence.15 This would not upset the European powers (especially Great Britain, which anxiously watched post-Napoleonic France’s first overseas conquest) or require a large and politically dangerous military commitment.

Historian Frederick Cooper’s observation that “European policy is as much a response to African initiatives as African ‘resistance’ or ‘adaptation’ is a response to colonial interventions” is borne out by the fate of the restricted occupation.16 The failure of the intermediaries through whom France sought to extend power to act subserviently doomed this project. For example, Hajj Ahmed, the bey of Constantine, refused the role offered him. Instead he used the interval to reform his administration and army in preparation for a showdown with the French. For his efforts the Ottoman Empire named Ahmed “Basha,” and in 1836 he won a startling victory over the French.17 Meanwhile, the emir Abdelkader forged an even more powerful challenge to the French.18 Heading a coalition of rural and urban elites, Abdelkader combined armed engagements (he was at war with the French 1832–34, 1835–37, and 1839–47) with diplomacy to wrest territory and concessions from Paris and forge the birth of an independent Algerian state.19

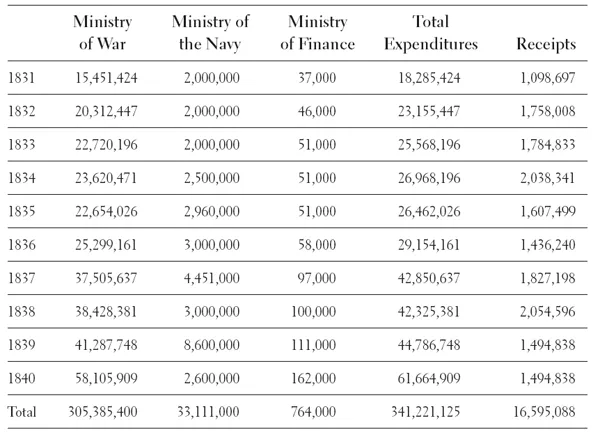

By the end of the decade, Louis-Philippe’s restricted occupation had ended. Ambitious military leaders chafed under the limitations placed upon them. Abdelkader sought to realize his own plans, which were increasingly at odds with the French. Moreover, the project was costing enormous sums (see table 1.1).

TABLE 1.1 Algeria: Governmental Expenses and Receipts, 1831–40 (francs)

Source: Le Moniteur universel, 30 April 1840.

The first decade of the occupation of Algeria had cost the government almost 350 million francs—a major sum. Despite this expense, the most precious commodity in Algeria, namely, security and order, remained elusive. Due to the political situation large stretches of the country were too dangerous for trade or travel. The French did not enjoy security far outside the areas they occupied, which at this time were limited to Constantine and the major Mediterranean ports of Oran, Algiers, Bône, and their immediate hinterland. The impossibility of the situation was underscored in 1839 when the fragile peace between Abdelkader and the French worked out in the Treaty of Tafna was definitively broken. Governor-General Vallée made his provocative “Portes de fer” march through territories he disputed with Abdelkader. The emir retaliated with bloody raids on unprotected European settlers in the Mitidja Valley, near Algiers. Abdelkader’s admonition to Vallée prior to his offensive (“Warn your travelers, your isolated settlers”) did little to offset the shock left in the wake of the killings.20 The emir’s forces spared few, leaving hundreds of decapitated bodies throughout the Mitidja’s remote farms.

Bugeaud’s Total Conquest, 1841–44

When the legislature met in January 1840, the deputies could scarcely contain themselves. Their rage over events in Algeria was compounded by lasting bitterness from the divisive 1839 elections and the dangerous international situation brewing in the eastern Mediterranean, the result of Muhammad Ali’s confrontation with the Ottoman Empire in Syria. In stormy sessions deputies heaped scorn upon the restricted occupation and called for vengeance. They had the king on their side. Louis-Philippe, feeling more confident, prepared to make a major military commitment in Africa. For the first time the government mentioned its readiness to send as many as one hundred thousand troops to Algeria.21

The debates continued throughout the summer.22 By year’s end Marshal Soult, the minister of war, set aside his reservations (viz. the threat of a military coup coming from the army in Algeria) and named Bugeaud to serve as Algeria’s governor-general on 29 December 1840. Bugeaud had already seen extensive service in Algeria and had coveted the powerful position at the head of the Algerian colony for some time. He had prepared the way for his nomination by using his seat in the Chamber of Deputies to ...