![]()

1

THE VICTORIAN IRISHMAN

The signature at the bottom of the stationery read Joseph I. Breen, the firm hand a fair index to the man holding the pen. Face to face, however, the name was always Joe Breen, the consummate insider, backstage operator, and go-to guy. For twenty years, from 1934 until 1954, he reigned over the Production Code Administration, the agency charged with censoring the Hollywood screen, an in-house surgical procedure officially deemed “self-regulation.” Though little known outside the ranks of studio system players, this bureaucratic functionary was one of the most powerful men in Hollywood. His job—really, his vocation—was to monitor the moral temperature of American cinema.

“Unless you are in the motion picture industry, you never have heard of Joe Breen,” Liberty magazine proclaimed in 1936, dragging the publicity-shy player on stage. Breen “probably has more influence in standardizing world thinking than Mussolini, Hitler, or Stalin. And, if we should accept the valuation of this man’s own business, possibly more than the Pope.” The subject of the profile would have conceded his obscurity, resented the comparisons, and grimaced at the glib line about the Holy Father. Yet Liberty was right to hype its scoop and pump its angle: Joe Breen was big Hollywood news that never made the fan magazines.

A former journalist, consular officer, and public relations man, Breen was first brought to Hollywood in 1931 by Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). Hays needed a well-connected and media-savvy Roman Catholic layman to mollify the most formidable constituency assailing Hollywood for purveying sin and profiting from its wages. By February 1934 Breen had wrangled control of the Studio Relations Committee (SRC), a weak-kneed advisory body tasked with enforcing screen morality. On July 15, 1934, he formally took charge of the Production Code Administration (PCA), the implacable new regime that replaced its toothless predecessor. Where the Studio Relations Committee made suggestions, the Production Code Administration gave orders.

Though popularly known as the Hays Office, the PCA was Breen’s domain. It was he who vetted story lines, blue-penciled dialogue, and exercised final cut over hundreds of motion pictures per year—expensive “A”-caliber feature films, low-budget B-unit ephemera, short subjects, previews of coming attractions, even cartoons. “More than any single individual, he shaped the moral stature of the American motion picture,” Variety reflected upon his death in 1965. “He was the most powerful censor of modern times, but he never looked upon himself as a censor, and, in truth, he wasn’t really a censor.”

In truth, he was—perhaps not in a strict legal sense, but for all practical purposes. Empowered by the MPPDA, fortified by a support system of millions of like-minded Catholics, Breen wielded a two-sided gavel forged of executive power and moral intimidation. Under the law school definition of censorship (a restriction on freedom of expression enforced by a state power), Breen was not a censor: he was an employee paid to maintain quality control by a consortium of private corporations. According to Will Hays and the studio chieftains, the review process overseen by Breen was an altruistic act of self-discipline, a solemn agreement among public-spirited businessmen that showed how seriously they took their great public trust, how they endeavored, always, to improve and uplift the American moviegoing public, upwards of 90 million customers per week, who sat spellbound and impressionable before the motion picture screen. “It is a mistake to think of the Production Code Administration as a form of censorship, a sort of policeman patrolling a beat,” insisted Arthur Hornblow, Jr., producer of Gaslight (1944), who likened the filmmaker’s fealty to the Production Code to the doctor’s to the Hippocratic Oath or the lawyer’s to the Canon of Ethics. “We are responsible members of a responsible profession, and the Code is the articulate enunciation of the ethical standards we have set up for ourselves.”

To modern ears, the hiss of pure gas leaks from such pronouncements, the prattle of coerced businessmen spouting the cant of the times, the cynicism laced with a generous dose of self-deception. Yet the insistence on terminology is more than a matter of semantics. The word censor conjures the image of a narrow-minded prude, a purse-lipped matron or stone-faced minister squeezing the life and pleasure out of art. The best-known cutters have lived up to the mirthless portrait: Thomas Bowdler, the British physician who sanitized Shakespeare and lent his name to the prissy editing that denudes literature of eros and spice, or Anthony Comstock, the anti-vice crusader of the Progressive Era who sniffed through the U.S. mail to confiscate, eliminate, and prosecute senders and receivers of birth control pamphlets or underwear catalogues.

Breen’s imprint on the Hollywood films he censored—or regulated—went deeper. No mere splicer of the negative, he was an activist editor with a positive goal for the motion picture medium. Bringing a missionary zeal to his custodial trust, he felt a sacred duty to protect the spiritual well-being of the innocent souls who fluttered too close to the unholy attractions of the motion picture screen. Yet mere inoculation was never his sole mission—always he sought to instruct, to shape, to nurture. Breen’s legacy rests not in what he tore out of but in what he wove into the fabric of Hollywood cinema.

Like Thomas Bowdler, who became a dictionary verb, the head of the Production Code Administration also lent his surname to the language. Though never part of the civilian vernacular, the word was lingua franca around the company town in the Golden Age of Hollywood. “Breening” was the process whereby a film was cut to fit the moral framework of Joseph I. Breen.

CATHOLICITY IN PHILADELPHIA

For all his prominence in the annals of Hollywood, relatively little is known of Breen: he left behind no authorized biography, no unpublished memoir, and no central repository of papers. Though a seasoned journalist, a devoted correspondent, and a tireless memo writer, he maintained a low public profile during his tenure and kept his mouth shut in retirement. For Breen, a scandalous tell-all book (and he would have had much to tell) was unthinkable. In a city lit by flashbulbs and swept by searchlights, he shunned the glare, seldom making the scene or being mentioned in the seen-around-town columns. More unusual for an A-list Hollywood power broker, he slid under the radar of official government surveillance: at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the keeper of thick files on countless second-tier screenwriters and bit players, Breen was barely a blip on the screen.

Out of camera range, Breen was impossible to miss. Even in a business of puffed-up egos and outsized personalities, he dominated the rooms he walked into, the full force of his charisma needing to be felt up-close, nose to nose. “Breen was the kind of person who, if you had dinner with him, you would know it,” understates his friend Martin S. Quigley, editor of the trade weekly Motion Picture Herald from 1949 to 1972.1 Sociable and loquacious, Breen was a lively raconteur who delighted in telling colorful anecdotes—some of them true—of his salad days as a newshound or his epic fights—some of them physical—with uppity directors. Yet he avoided the limelight the rest of the town craved. “Incredible as it may seem, and despite the fact that I come from Hollywood, I have no picture of myself to send you,” he informed an admiring Catholic journalist in 1944. “I am probably the only person connected directly or indirectly with the motion picture industry in Hollywood who has not, at some time or other, sat for a photograph.” His life must be pieced together from official records, trade press accounts, private letters, oral histories, Hollywood memoirs, and the occasional interview or written statement of principle. Above all, a sense of the man is best gleaned from the correspondence, memos, and documents contained in what is his chief legacy in print, the files of the Production Code Administration, a treasure trove of backstage infighting and evidence aplenty of Breen’s extraordinary impact on the main currents of American cinema.

Given the territory, the temptation to filter Breen’s life story through the lens of a vintage Hollywood biopic is well nigh irresistible. Streetwise and tough, unabashedly ethnic and intermittently corny, the first treatment bows to formula and traffics in clichés: the two-fisted Irishman going Hollywood to take center stage in a gruff Warner Bros. melodrama. Certainly he would be wrong for the starring role in the classy Great Man paeans from MGM or the spicy scenarios favored by the European refugees over on the Paramount lot. Cast the genial Pat O’Brien in the lead, not James Cagney (too edgy) or John Barrymore (too wasted) or Edward G. Robinson (too Jewish), and watch for shades of gray and moody undertones beneath the surface.

Joseph Ignatius Breen was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on October 14, 1888, six years before the official birth date of the movies and nine before radio.2 His was the last generation of Americans whose childhood was not flooded with a torrent of projected images and broadcast sounds, the last generation to reach adulthood before the Great War shattered the hubris of Western civilization, the last generation whose public morals and formal manners were literally Victorian. It was never an age of innocence, but it was an age of fixed boundaries and firm lines, straight-laced and stiff-necked, of women encased in corsets and bound in stockings, of gentlemen adorned in greatcoats and top hats, of watchful chaperones supervising chaste courtship rituals before the automobile propelled young lovers down a bumpier road. Well into the 1950s, decades behind the fashion curve, Breen cradled his keys on a chain suspended from his vest pocket.

Breen traced his roots to the West of Ireland, his father, Hugh A. Breen, immigrating to America “in his manhood, after a stretch of curious activity which found no favor with the British Constabulary,” as his son wryly put it. Bypassing Boston and New York, the elder Breen found his wife, Mary Cunningham, in West Hoboken, New Jersey, and continued inland to settle in Philadelphia.

Though not as polyglot as New York or as Irish as Boston, Philadelphia in the last quarter of the nineteenth century was an urban melting pot where the Irish mingled with an exotic mix of Italians, Poles, Jews, and more traditional stocks. A skeptical native son, Breen despised the corrupt Republican machine that ran Pennsylvania and lamented the bovine complacency of the electorate that tolerated it. “Nearly everybody in Philadelphia votes the Gang ticket,” he observed in adulthood, and “cares nothing whatever for the character of its municipal government.” Still, in a moment of W. C. Fields–like reverie, Breen admitted that “Philadelphia is not quite so bad as it is represented to be.”

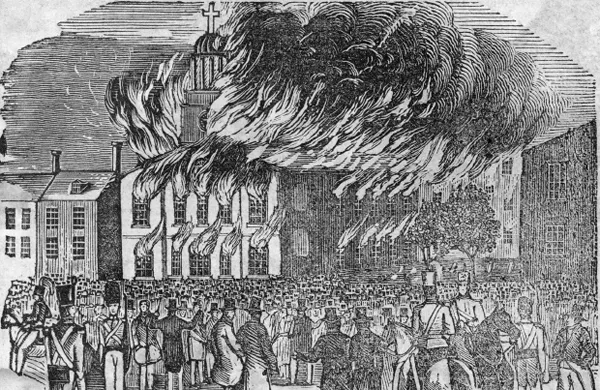

Know-Nothing nativism: a contemporary illustration of the anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia in 1844.

Industrious and ambitious, Hugh Breen made the transition from shanty to lace curtain Irish in one generation, accumulating a modest fortune, said his son, “by way of the barter and sale of real estate in the up-and-coming community which goes by the name of West Philadelphia.” Settling in the respectable Fairmount Park district of the city, the Breens were prominent enough to welcome as dinner guests such local luminaries as Kid Gleason, the second baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies (and later heartbroken manager of the infamous Black Sox in the 1919 World Series) and the sports journalist and humorist Arthur “Bugs” Baer.

By Irish immigrant standards, Hugh and Mary Breen raised a medium-sized family. Joe was the youngest of three sons—his eldest brother, Francis A. Breen, entered the priesthood and for forty years devoted himself to the Society of Jesus, including service as treasurer both at St. Joseph’s College and on the Jesuit weekly, America. James J. Breen entered another text-intensive profession and became a prominent Philadelphia attorney and local politician. Two sisters—Marie, who never married, and Catherine, who wed a prosperous Philadelphia businessman named Thomas Quirk—completed the Breen family. With equitable symbolism, the career paths of the Breen boys traced the three main-traveled roads for upwardly mobile Irish-Americans in the twentieth century: religion and education (Francis), law and politics (James), and media and culture (Joseph).

The progress of the Breens up the ladder of success was smoothed by earlier arrivals forced to claw their way on to the first rung. Though the Irish had been flocking to America since the famines of the 1840s, led by their stomachs to build the railroads, run the saloons, and swell the enlisted ranks of the U.S. Cavalry, the settled population resisted the influx of emaciated refugees. Pamphlets denounced the Irish as vile “bog trotters” and editorial cartoons portrayed bewhiskered hooligans tumbling into paddy wagons after drunken donnybrooks. In the 1850s, the Native American Party, the so-called Know-Nothings, thrived on an anti-immigrant platform synthesized in a popular acronym for both the preferred employee and citizenship pool: NINA—No Irish Need Apply. The Irish, the Know-Nothings knew, were not bred for “the moderation and self control of American republicanism.”

More than the land of origin, however, the resilient Catholicism of the Irish was the true stain of un-American-ness. “Popery is opposed in its very nature to Democratic Republicanism,” wrote Samuel F. B. Morse, sending out a common message. Adherents of a creed cloaked in black robes and reeking of papist intrigue, Catholics pledged a treacherous allegiance to the foreign flag of the Vatican. Convents, seminaries, the parochial school system, and Catholic fraternal societies were under constant attack as incubators of Jesuitical subversion and nests of perverse sexuality.

Repudiating its Quaker roots, the City of Brotherly Love spawned one of the most spectacular outbreaks of anti-Catholic violence. In 1844, nativist mobs (“inflamed by the spectacle of many flourishing Catholic congregations in the city and its environs”) ran riot in the streets, burning to the ground two Catholic churches and a convent. “The Irish Catholics were the foreigners against whom the opposition was directed,” wrote Father Joseph L. J. Kirlin, the official historian of the archdiocese, in Catholicity in Philadelphia in 1909, himself still inflamed by the abuse hurled at his people (“Irish papists,” “the miscreant Irish,” “the degraded slaves of the Pope”). Breen grew up hearing tales of anti-Catholic mobs torching convents and seeing Thomas Nast cartoons depicting Catholic prelates as ravenous crocodiles invading the shorelines of Anglo-Protestant America.

The Civil War tempered some of the nativist bile. Mustered out of the Grand Army of the Republic, returning East or going West, Irish veterans claimed payment on the investment made in blood. Across New England and the Midwest, they waved the bloody shirt at election time and seized power from the older Northern European stocks. Exploiting a fluency in English and a familiarity with Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence often gained from the wrong end of the law, the Irish prospered in politics, business, and journalism.

The ascent of the Irish met periodic waves of backlash from inheritors of the Know-Nothing tradition, who might overlook the home country but never the faith. The 1890s witnessed a spike in nativist sentiment against Irish Catholics, in no small part because avid hustlers like the Breens were making it in America, scrambling up the economic ladder and nudging aside—leaping over—the underachieving sons of the genteel Protestant establishment. “One Irish name equaled a Catholic and that equaled mud,” recalled a man who was both in 1890s America. From everyday social slights to official sanctions, Irish Catholics had reason to feel themselves a subaltern people in a rigged caste system.

Ambitious Irish-Catholic families like the Breens channeled their energies into religion, education, and politics, which were often the same thing. Insular by necessity, and perhaps instinct, they closed ranks in parochial schools and Jesuit universities, at the Knights of Columbus and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, in Ladies Sodalities and Catholic Women’s Clubs—the institutions and associations that served as boot camps and officer’s can...