eBook - ePub

Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Sexual Science and Clinical Practice

Richard Friedman, Jennifer Downey

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Sexual Science and Clinical Practice

Richard Friedman, Jennifer Downey

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book bridges psychoanalytic thought and sexual science. It brings sexuality back to the center of psychoanalysis and shows how important it is for students of human sexuality to understand motives that are often irrational and unconscious. The authors present a new perspective about male and female development, emphasizing the ways in which sexual orientation and homophobia appear early in life. The clinical section of the book focuses on the psychodynamics and treatment of homophobia and internalized homophobia.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy by Richard Friedman, Jennifer Downey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Theoretical / Developmental

Introduction to Part 1

This book, written for psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapists, is divided into two parts, scientific/theoretical and clinical. The sections may be read independently or in reverse order. Clinicians working with gay patients who wish to focus on the treatment of internalized homophobia, for example, may wish to get directly to the clinical part of the book and return to the more scientific/theoretical section at leisure. The authors are psychiatrist-psychoanalysts, graduates of the Center for Psychoanalytic Studies of Columbia University, and engaged in the practice of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy in New York City.

Many traditionally trained psychodynamically oriented clinicians have remained wedded to concepts we now know require revision in light of a knowledge explosion in extra-analytic fields. Our goal in writing the first part of this book was to build bridges between psychoanalysis and these other disciplines. We could not be all inclusive and while respecting the importance of anthropological and sociological research, we focused on other areas. We attempted to integrate selected aspects of extrapsychoanalytic research in genetics and psychoendocrinology, psychological development, and sexology with psychoanalytic theory. Consideration of research from these disciplines, in addition to psychoanalytic observations, results in rich, complex, and empirically supported paradigms of female and male development.

Although Freud’s insights about sexual functioning were at the center of psychoanalysis at its inception, the field seems to have moved further and further away from discussion of human sexuality. Much of our emphasis in the first part of this volume is on distinguishing Freud’s observations and speculations that remain useful today from those that have not stood the test of time. We particularly emphasize his theory of the Oedipus complex in that regard.

Among the most important revisions in psychoanalytic, developmental, and clinical theories in recent years are those pertaining to homosexual orientation. Discussion of psychoanalytic psychology and homosexuality, because of political controversy, has sometimes been difficult. Throughout this book we stress the need for healthy scholarly inquiry into controversial areas that are often plagued by heated ideological and political debates.

Psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapists are faced with the same challenges as everyone else in adapting to a rapidly changing world in which new networks of information organization and transfer emerge day by day. On the one hand, the analytic couch, both symbolically and as a practical therapeutic modality, seems to us to remain as vital as, for example, Shakespeare’s plays. On the other hand, modern developments seem to support the wisdom of those analysts who presciently argued for the usefulness of a systems approach to the understanding of human behavior, at a time when it was not entirely fashionable to do so (Engel 1977). In that respect, recent observations by Thomas Friedman, a social and political critic, seem particularly apt:

When dealing with any non-linear system, especially a complex one, you can’t just think in terms of parts or aspects and just add things up and say that the behavior of this and behavior of that added together makes the whole thing. With a complex non-linear system you have to break it up into pieces and then study each aspect and then study the very strong interaction between them all. Only this way can you describe the whole system.(Friedman 1999:28)

The material we discuss in the following chapters is best viewed from the perspective of a complex systems approach, with interactions occurring at many levels of organization from single cells to large social groups.

1

Sexual Fantasies in Men and Women

A major theme of this volume is that males and females develop along different pathways. There are many reasons for thinking this, including the psychoanalytic treatment and study of gay men and lesbians. The brains of men and women are differentially influenced in utero by sex steroid hormones. This difference influences psychological development in many ways. The minds of boys and girls, men and women, develop differently; and important aspects of sexual experience and activity are unique to each sex and not shared by the other. Sexual orientation of any type—homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual—is best conceptualized as part of the psychology of men or the psychology of women. Sadly, both lesbians and gay men are often discriminated against because of their homosexual orientation. The reasons for and manifestations of this, however, differ by gender. Sex differences in the causes and consequences of homophobia are discussed throughout this book.

We focus on sexual fantasy in this chapter because of its central role in sexual orientation, motivation, and psychoanalytic psychology. It is helpful as a point of departure to be aware of psychoanalytic observations about general aspects of fantasy.

Characteristics of Fantasy

Freud suggested that daydreams—or fantasies—were a continuation of childhood play: “The growing child when he stops playing, gives up nothing but the link with real objects; instead of playing he now phantasizes. He builds castles in the air and creates what are called day dreams” (1907, cited in Gay 1989:439). Person has pointed out that fantasies are a type of imaginative thought that serves many different functions (Person 1995). As Freud observed, they may represent wishes evoked in response to frustration in order to convert negative feelings into pleasureful ones. Fantasies may also soothe, enhance security, and bolster self-esteem or repair a sense of having been abandoned or rejected. Fantasies may (temporarily) repair more profound damage to the sense of self that occurs as a result of severe trauma. They also frequently serve role rehearsal functions, as occurs, for example, in little girls who consider dolls to be their “babies” and play “house” as preparation for becoming adult homemakers. Organized as images, metaphors, and dramatic action, fantasies in the form of artistic productions and mythology have been part of the human heritage probably for the entire life of our species. Freud provided a new framework for understanding these universal forms of human expression by noting that they could be critically analyzed like all other products of the mind.

The Meanings of Fantasy: Conscious and Unconscious

The story line of a fantasy, meaningful in itself, also symbolically expresses additional hidden meanings. Underneath one narrative is another, and under that yet another, arranged in layers as is the mind itself. A fundamental discovery of Freud’s and one that remains valid today (unlike many of his ideas about human sexuality) is that some aspects of mental functioning are not subject to conscious recall and that even when unconscious, they may influence motivation. Connections between conscious and unconscious thoughts, feelings, memories occur in the form of “associations.” Just as neural networks exist in the brain, so do psychic networks in the mind, although the precise correspondences between the two has not been clarified (Freud 1900, 1915–1916, 1916–1917; Olds 1994). Freud termed his unique method of exploring the pathways of these connections psychoanalysis. His initial explorations in his self-analysis carried out at the end of the nineteenth century led to the recognition that the closer one comes to mental processes that are out of awareness, the more the rules governing mental organization appear to change. Whereas the thinking processes of our ordinary daily life are more or less “logical,” unconscious mentation seems to be organized more like dreams. In dreams many ideas, memories, and feelings may be represented by a single image. For example, a grandfather clock may represent the passage of time, one’s grandfather, a special occasion upon which the grandfather clock was purchased, a meaningful past residence that had a grandfather clock, and so on. The narrative line of a dream consists of strings of such symbols and emotions that may or may not be ordinarily connected with the images as usually experienced during waking life, all arranged without regard to ordinary time/space rules of the physical universe. For example, someone may dream that a long dead parent was riding a horse and experience in the dream an unaccountable feeling of terror. Or that he was playing in a tennis match even though he had never learned tennis. In dreams anyone can be anyone—man, woman, or child, or even nonhuman—and all is possible. Anything that the mind can imagine can occur in a dream. Freud termed the organization of the unconscious part of the mind the primary process and contrasted it with the secondary process—the system of organization of ordinary, everyday thinking (Freud 1900). A perspective about fantasy unique to psychoanalytic psychology is that beneath the immediately coherent narrative line of waking fantasy are disguised stories that carry hidden meanings. These latent narratives consist of memories of real and imagined events linked in the imagination of the present. Since single symbols can represent multiple meanings, the amount of information carried by sequences of symbols is obviously vast. Beneath the apparently clear meaning of a specific fantasy, therefore, are networks of other meanings.

Another core psychoanalytic idea is that one reason that some story lines are unconscious is that they contain wishes that are unacceptable to the conscience. The mind has the capacity to erase from its awareness certain unpleasant ideas but not the power to completely eliminate their motivational force. For example, a patient dined with a disliked business competitor. Early in their talk he thought: “This guy is such a pain in the neck I wish he would drop dead”—and later “I need this conversation like a hole in the head.” That night he dreamt he was riding in a stagecoach with a masked stranger. Pulled by huge black horses, the coach entered a dense forest. Suddenly the stranger pulled off his mask. It was Dracula! The patient pulled a long pencil from the inner pocket of his jacket and stabbed the vampire in the head. His associations led to monster movies, childhood competition with rivals, and, finally, to the hated colleague whom he had wished would die.

Raised by the paradigms presented thus far are important questions: How are symbols and stories selected by individuals and endowed with the dramatic meanings that characterize life narratives? When are they selected? What are the factors influencing the selection process? How changeable are consciously experienced fantasies? Are the links between conscious and unconscious fantasies fixed and irreversible, or are they potentially modifiable? We discuss some of these questions in this chapter, but they remain important throughout this book. We return to consider them in the clinical sections later on as well.

Definition of Sexual Fantasy

Psychoanalysis is a depth psychology that originally emerged from the study of sexual fantasy. A problem present in the field from its inception, however, has been lack of a definition of erotic fantasy, or even a general sense of agreement about its specific attributes. One reason for this may be that Freud blurred the distinction between the sexual and that which nonpsychoanalytically oriented clinicians might consider nonsexual. In his last published work, Outline of Psychoanalysis (1940), he commented:

It is necessary to distinguish sharply between the concepts of “sexual” and “genital.” The former is the wider concept and includes many activities that have nothing to do with the genitals. Sexual life comprises the function of obtaining pleasure from zones of the body—a function which is subsequently brought into the service of that of reproduction. (Freud 1940:23)

Freud hypothesized that “erotogenic zones” under the influence of a sexual instinct invested certain areas of the body with intense pleasure during specific phases of development—oral, anal, and phallic. We agree with psychoanalytic scholars who have argued that Freud’s libido theory has not withstood the test of time (Kardiner, Karush, and Ovesey 1959; Person 1980). The psychoanalytic literature contains countless articles, nominally about sexuality, discussing bodily zones invested with so-called libidinal energy. We consider the libido theory, which placed sexual “energy” at the center of all human motivation and all psychopathology, to be of historical interest only, although this position puts us at odds with beliefs that are popular among many psychoanalysts, particularly in Europe and Latin America. Libido theory is not accepted by modern neuroscientists or psychologists (Kandel 1999), and it is important to integrate psychoanalytic theory and practice as much as possible with modern nonpsychoanalytic knowledge. Thus, when we refer to “sexual” or “erotic” fantasies in this article, our meaning is closer to Freud’s narrower one (pertaining to the “genitals”), although influenced by research that took place during the decades following his death.

The topic of sexual fantasy is more complex in women than men, and we reserve consideration of its meaning(s) in women until later in this chapter. The first part of the chapter therefore is about sexual fantasy in men.

In this book we define sexual fantasy as mental imagery associated with consciously experienced feeling that is explicitly erotic or lustful. Sexual lust is a specific type of affect. The imagery is nearly always organized in some type of narrative format. Since this volume is directed at readers who are interested in psychoanalytic thought and psychodynamic therapy and are familiar with the concept of unconscious fantasy, we emphasize here that imagery, story line, and erotic feelings of the sexual fantasies we refer to are generally reportable, not unconscious. We discuss situations in the clinical section of this book in which individuals may find it difficult to describe their sexual fantasies. Nevertheless, they tend to be aware of them.

The narrative line of a sexual fantasy tells a more or less elaborated story of objects and situations associated with erotic arousal. Sexual emotion (lust) is associated with physiological changes throughout the body including the central nervous system. Sexual fantasy often occurs during masturbation and during sexual activity. It may be stimulated by pornography (in males more frequently than females) and/or romance fiction (in females more frequently than males) and is often experienced spontaneously (Leitenberg and Henning 1995).

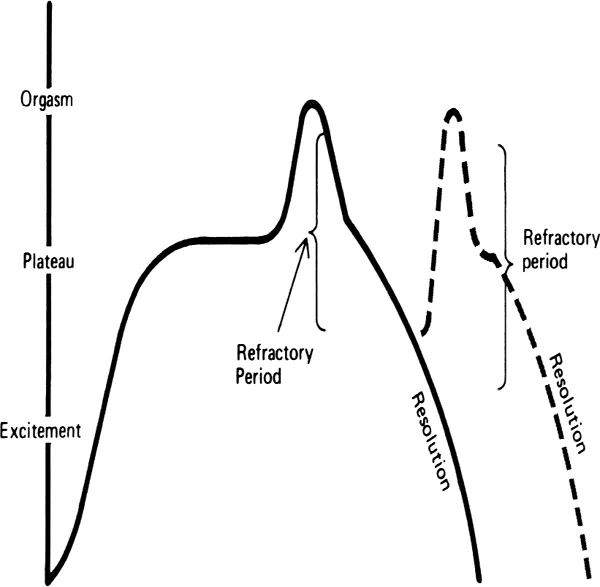

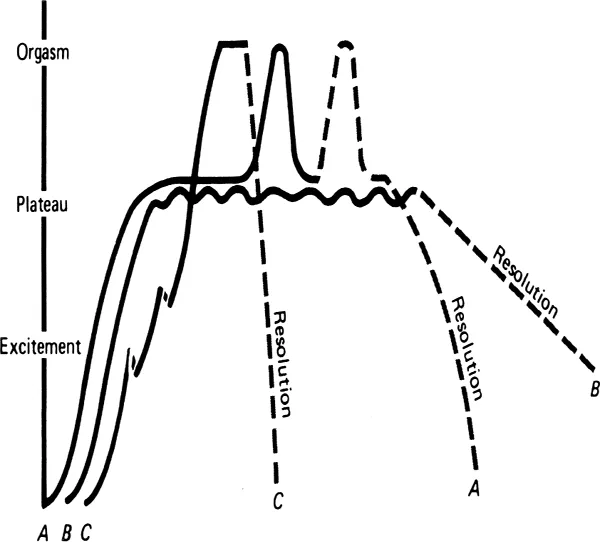

Masters and Johnson and Kaplan

In thinking about sexual fantasy, we find Masters and Johnson’s famous depiction of the sexual response cycle and Kaplan’s revision of it helpful (Masters and Johnson 1966). According to the Masters and Johnson model, sexual response begins with the subjective feeling of sexual excitement and its attendant physiological changes (vasocongestion of the genital organs, increases in heart and respiratory rate, etc.). The excitement phase builds until orgasm takes place. For a certain amount of time thereafter, the individual, if male, will be in a refractory or “recovery” period during which orgasm is not possible. The male model is diagrammed in figure 1 below. Masters and Johnson pointed out that women’s sexual response is more variable. As can be seen from their model of the female sexual response cycle (figure 2), some women, though sexually excited, will not reach orgasm but will rather experience what Masters and Johnson called a plateau of sexual arousal before resolution. Others will experience a single orgasm similar to the male model. Still others are capable of multiple orgasms before they go into the refractory period when no orgasm is possible. During the so-called refractory period, sexual fantasy diminishes, only to surge again with the return of sexual desire and sexual excitement.

FIGURE 1.1. The male sexual response cycle. From Masters and Johnson, Human Sexual Response, p. 5 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966). Reprinted with permission from Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

FIGURE 1.2. The female sexual response cycle. From Masters and Johnson, Human Sexual Response, p. 5 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966). Reprinted with permission from Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

Kaplan, a psychoanalyst and sex therapist, observed on the basis of the patients whom she saw that many sexual difficulties seemed to begin before the sexual response cycle as described by Masters and Johnson. She termed this preliminary phase sexual desire. Many of the patients referred to Kaplan complained that they experienced no sexual interest. Kaplan made a distinction between sexual desire and sexual excitement, noting, “Sexual desire is an appetite or drive which is produced by the activation of a specific neural system in the brain, while the excitement and orgasm phases involve the genital organs” (Kaplan 1979:9). She asserted that sexual desire is experienced as specific sensations that motivate the individual to “seek out or become receptive to sexual experience” (10) Kaplan proposed therefore an early phase of the sexual response cycle when central nervous system changes theoretically occurred and preceded genital changes. In men, however, at least in laboratories studying sexual function, erotic feelings are associated with increased penile blood flow, that is, some degree of erection (Freund, Langevin, and Barlow 1974).

Freud believed that fantasies were the product of wishes that compensated for “unsatisfying reality.” Empirical studies of sexual fantasy do not support this, however. Sexual fantasies occur most frequently in people with high rates of sexual activity and little sexual dissatisfaction. Of course, clinically, many patients experience impulsive/compulsive driven sexuality. These individuals are different from relatively healthy people, however, who happen to be highly sexual (Leitenberg and Henning 1995).)

The Components of Sexual Fantasy

Erotic fantasy, as we have discussed above, consists of a few specific components, including a sexual object—usually a human being—either male or female or both. A story line is often present in which the sexual object is involved in a specific situation, such as embracing, engaging in oral sex or intercourse, or undressing. What makes a fantasy erotic, however, is its invariant association with sexual feeling. We do not consider fantasies to be sexual unless the erotic feeling component is present. Erotic fantasy may motivate erotic activity with others or masturbation. It does not always do so, however, and may be experienced privately in the theater of the fantasist’s mind.

In both sexes sexual feelings depend on adequate blood levels of androgen. Pharmacological blockage of the effects of a...