- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The destruction of Nimrud and Palmyra, crumbled shells of mosques in Iraq, the fall of the World Trade Center towers on 9/11: when architectural totems such as these are destroyed by conflicts and the ravages of war, more than mere buildings are at stake. The Destruction of Memory, now with a new preface, argues that such destruction not only shatters a nation’s culture and morale but is a deliberate act of eradicating a culture’s memory and, ultimately, its existence. A film of the same name based on the book will be released in early 2016.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Destruction of Memory by Robert Bevan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION: THE ENEMIES OF ARCHITECTURE AND MEMORY

The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader or some ruling clique controls not only the future but the past. If the Leader says of such and such an event, ‘It never happened’ – well, it never happened . . . This prospect frightens me much more than bombs – and after our experiences of the last few years, that is not a frivolous statement.

GEORGE ORWELL1

There never were any mosques in Zvornik.

BRANKO GRUJIC, SERBIAN MAYOR OF ZVORNIK (after its Muslim population had been expelled and its mosques destroyed2)

THERE IS BOTH A HORROR and a fascination at something so apparently permanent as a building, something that one expects to outlast many a human span, meeting an untimely end. As an architecturally obsessed child I was often absorbed in film footage of the destruction wreaked on Europe’s built heritage by the Second World War, or I could be found in the local branch library dragging volumes, half my height, about vanquished treasure houses over to the carpet tiles of the junior section. At the same time it felt wrong even to be considering the fate of inanimate art objects and architecture in the face of the contemporaneous footage demonstrating the perverse suffering inflicted on people in the Holocaust. The latter was by far the greater evil and infinitely more moving. Dwelling even for a moment on the shattered remains of museums and churches felt, at best, self-indulgent and, at worst, an indication of warped priorities, especially as the Holocaust had touched the lives of family friends terribly.

The levelling of buildings and cities has always been an inevitable part of conducting hostilities and has worsened as weaponry has become heavier and more destructive, from the slings and arrows of the past to the daisycutters of today. Continents rather than cities can be devastated. This damage may be the direct result of military manoeuvres to gain territory or root out a foe, or a desire to wipe out the enemy’s capacity to fight. The division of the spoils also plays a part. But there has always been another war against architecture going on – the destruction of the cultural artefacts of an enemy people or nation as a means of dominating, terrorizing, dividing or eradicating it altogether. The aim here is not the rout of an opposing army – it is a tactic often conducted well away from any front line – but the pursuit of ethnic cleansing or genocide by other means, or the rewriting of history in the interests of a victor reinforcing his conquests. Here architecture takes on a totemic quality: a mosque, for example, is not simply a mosque; it represents to its enemies the presence of a community marked for erasure. A library or art gallery is a cache of historical memory, evidence that a given community’s presence extends into the past and legitimizing it in the present and on into the future. In these circumstances structures and places with certain meanings are selected for oblivion with deliberate intent. This is not ‘collateral damage’. This is the active and often systematic destruction of particular building types or architectural traditions that happens in conflicts where the erasure of the memories, history and identity attached to architecture and place – enforced forgetting – is the goal itself. These buildings are attacked not because they are in the path of a military objective: to their destroyers they are the objective.

Such was the purpose of the Nazi destruction of German synagogues on Kristallnacht in 1938: to deny a people its past as well as a future. More than this, Kristallnacht, as I argue in this book, can be seen as a proto-genocidal episode – an act of dehumanization and segregation and a further step down towards the limitless dark cellars of barbarism. The erasure of architecture is a crazed and dusty reflection of the fortunes of people at the hands of destroyers. During the 1990s the wars in the former Yugoslavia, with the torture, mass murders and concentration camps of Bosnia on the one hand and the razing of mosques, the burning of libraries and the sundering of bridges on the other, made me realize that my childhood guilt at considering the fate of material culture was misplaced. The link between erasing any physical reminder of a people and its collective memory and the killing of the people themselves is ineluctable. The continuing fragility of civilized society and decency is echoed in the fragility of its monuments. This cultural cleansing, with architecture as its medium, is a phenomenon that has been barely understood. It is the reason this book has been written. The research has been informed by visits to many places, from India to Bosnia, from the West Bank to Ireland. It has been compiled using my own interviews, reports filed by other journalists and the work of many specialist academics, historians, campaigning bodies and human rights groups around the world.

One casuality of Germany’s Kristallnacht was the vast synagogue of 1911–13 at Essen designed by Edmund Körner. Its interior was largely destroyed by fire, but the structure survived and was used after the war as a design museum (which destroyed any remaining fittings) before becoming a Holocaust memorial in 1979. A recent attempt to begin Jewish services there once again has been resisted by politicians in the city, who have argued that this would upset the ‘neutrality’ of the memorial space.

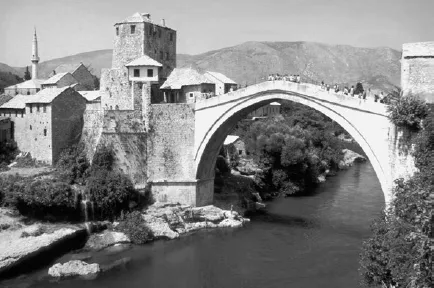

Mostar’s Stari Most before the Bosnian war. The symbol and social hub of the once cosmopolitan city of Mostar, the bridge (1566) was designed by Mimar Hajruddin, a pupil of the great Ottoman architect Sinan. It is flanked by two 17th-century fortified towers.

Following concentrated shelling by Croat gunners, Mostar’s bridge fell into the Neretva river on 9 November 1993. It was a catastrophic loss captured in unique footage by an amateur cameraman. The stone bridge has since been rebuilt in replica. For ordering its destruction, Croat General Slobodan Praljak has been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia at The Hague.

Much has been written about the deliberate repression of minority cultures – their language, literature, art and customs – but little about the repression of their architecture. This book looks at how the experiences of people and architecture under fire have gone hand in hand over the last century, at how architecture has become a proxy by which other ideological, ethnic and nationalist battles are still being fought today. Numerologists could have a field day with this matériel: Kristallnacht began just before midnight on 9 November, the 9/11 of 1938. On the same date in 1989, the first sections of the Berlin Wall began to tumble. Four years later on 9/11, Stari Most, Mostar’s historic bridge, was finally brought down into the Neretva river by Croat gunners. Then, of course, came 9/11 in New York – a different day, of course, given the date sequencing used in North America – but the numerals do seem to mark a day for destruction. This is not to make the case for some sort of cosmic agency at work – other dates could equally be matched up for their destructive significance. Such coincidences are possible because of the ubiquity of the deliberate and meaningful destruction of architecture and monuments.

I begin with an examination of the fate of buildings as part of genocide and ethnic cleansing and go on to examine the targeting of buildings in campaigns of terror and conquest, in the structures erected and demolished to keep peoples apart or force them together, and those levelled at the hands of revolutionary new orders that want to build Utopia on the ruins of the past. There is a bestial carousel quality to the past century’s destructive activity: ethnic cleansing can be part of conquest; conquest can be ideological as well as territorial; territorial acquisitiveness can be genocidal and end up in partition. The coverage is thematic rather than geographical or chronological in order to bring connections to bear more readily. Such themes inevitably overlap; the fate of Jerusalem’s buildings since the creation of Israel, for instance, could equally be looked at as an example of ethnic cleansing, partition or conquest (where it appears in this book). It aims to weave together some of these threads (it is too widespread an experience to hope for comprehensive coverage) to show the forces at work leading to the targeted destruction of architecture beyond that caused by purely military considerations. It looks at the political forces at work in order to make plain the politicized nature of what is happening when China demolishes Tibet’s monasteries or Berlin struggles with its National Socialist and Stalinist past. Why did al-Qaeda decide that the World Trade Center was a suitable target and why did the Taliban defy world opinion and reduce the Bamiyan Buddhas to dust? Clausewitz’s well-known dictum, ‘War is not an independent phenomenon, but the continuation of politics by different means’, is the thinking behind the architectural dismemberment under examination.

THE VIOLENT DESTRUCTION OF buildings for other than pragmatic reasons also happens in peacetime, of course, and it is impossible to separate out fully the depredations of ‘progress’ – modernity and industrialization, with all their implicit ideological content – from conflicts between classes and other groups within societies that are all part of the continuous remaking of our environments; as cities evolve and change, so structures become redundant or more valuable uses for a site are found.3 Demolition has often been deployed to break up concentrations of resistance among the populace; the Haussmannization of Paris is the most obvious case (although this too was in the wake of violent revolutionary upheavals). Benign or culpable neglect is the more common phenomenon. This may include the bastardization or demolition of a building that no longer has a community to serve it or where its builders lack the economic or political power to resist threatening ‘regeneration’ or ‘improvement plans’.

It accompanies the decline in the power or presence of a community, ethnic or religious group, or class in a locale, or, conversely, can reflect hostility to a group’s rise (every time a Bangladeshi family in London’s East End gets petrol-soaked rags pushed through its letterbox, this is ethnic cleansing in miniature). That which is valued by a dominant culture or cultures in society is preserved and cared for: the rest can be mindlessly or purposefully destroyed, or just left to rot. These issues are touched upon where the legacy of conflict still determines a country’s demolition and rebuilding decisions, or where a country is fragmenting as war approaches. The wars and revolutions of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, however, where these processes are at their most explicit and brutal, and are pursued with a brutality that escalates with the conflict, are the focus of this book. The intentional collapse of buildings is intimately related to social collapse and upheavals.

It should be remembered, though, that there is nothing intrinsically political about the style of a city’s buildings: classicism as an aesthetic, for instance, has served well as an urban model for fascism, Stalinism or liberal democracy in Berlin, Moscow and Washington, DC. Modernism, too, while excoriated by Hitler and long linked to the left, found a role in Mussolini’s Italy. That is not to say that the design and production of architecture is free from ideological content; quite the opposite, it is saturated with it. But this content is not inherent in form but arises when those forms are placed in a societal and historical context. It is the ever-changing meanings brought to brick and stone, rather than some inbuilt quality of the materials or the way in which they are assembled, that need to be emphasized. Fundamentally it is the reasons for their presence and behind the desire to obliterate them that matter. Buildings are not political but are politicized by why and how they are built, regarded and destroyed.

András Riedlmayer, who has been a vigorous campaigner against the destruction of Bosnia’s and Kosovo’s cultural heritage, quotes historian Eric Hobsbawm in relation to the context for this ideology of destruction:

History is the new material for nationalist, or ethnic, or fundamentalist ideologies, as poppies are the raw material for heroin addiction . . . If there is no suitable past it can always be invented. The past legitimises. The past gives a more glorious background to a present that doesn’t have much to show for itself.4

Such uses and abuses of the historical record to reconstruct or re-represent the past as evidenced by attacks on architecture are legion. Hobsbawm has also argued that the invention of new traditions is an essential part of creating continuity with the past, often in the interest of creating nationalist loyalties. Singing a national anthem, reinvigorating indigenous crafts or waving resurrected historic symbols and flags, he says, activate this invented continuity by dint of repetition.5 Rather than relying on repetition, I would argue that the virtue of a built record to this method of ideological production lies in the apparent permanence of bricks and stone. Buildings and shared spaces can be a location in which different groups come together through shared experience; collective identities are forged and traditions invented. It is architecture’s very impression of fixity that makes its manipulation such a persuasive tool: selective retention and destruction can reconfigure this historical record and the façade of fixed meanings brought to architecture can be shifted.

The loss felt by those whose architectural patrimony has been reduced to rubble is not simply dismay at the material cost involved or sorrow over the mutilation of the aesthetic worth with which the structures are regarded. Rather, as Hannah Arendt has argued: ‘The reality and reliability of the human world rests primarily on the fact that we are surrounded by things more permanent than the activity by which they were produced.’6 To lose all that is familiar – the destruction of one’s environment – can mean a disorientating exile from the memories they have invoked. It is the threat of a loss to one’s collective identity and the secure continuity of those identities (even if, in reality, identity is always shifting over time). The philosopher Henri Lefebvre noted this process: ‘Monumental space offered each member of a society an image of that membership, an image of his or her social visage . . . It thus constituted a collective mirror more faithful than any personal one.’7 This is a step onwards from Lacanian mirror theory; instead of the developing individual recognizing himself as a discrete entity, it is about tying that individual back into a wider community. It is about belonging.

External threats can rally even heterogeneous groups together in defence of a national cause and the architectural representations of statehood. By contrast, in wars between ethnic or religious groups, either within a country or across its borders, there is an atomization, a rallying not to the national flag but to their sub-national communities. Here personal identity – the individual self grounded within the collective self – is in danger. In these circumstances there is an intensification of allegiance to the group reflecting a desire for preservation. Ethnicity or religious identification, for instance, can become more important than identifying with a neighbourhood, city or nation-state. It is, in part, this fear of oblivion and defence against it that can make these conflicts so brutal and the destiny of architectural representations of group identity so vital. Nietzsche, identifying in monuments ‘the stamp of the will to power’, could easily have written the same regarding their demolition as their building. A particular barbarism is fostered in wars between such groups, even if their manifestations sometimes disguise essentially p...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

- 1 INTRODUCTION: THE ENEMIES OF ARCHITECTURE AND MEMORY

- 2 CULTURAL CLEANSING: WHO REMEMBERS THE ARMENIANS?

- 3 TERROR: MORALE, MESSAGES AND PROPAGANDA

- 4 CONQUEST AND REVOLUTION

- 5 FENCES AND NEIGHBOURS: THE DESTRUCTIVE CONSEQUENCES OF PARTITION

- 6 REMEMBER AND WARN I: REBUILDING AND COMMEMORATION

- 7 REMEMBER AND WARN II: PROTECTION AND PROSECUTION

- REFERENCES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PHOTOGRAPHIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INDEX