![]()

| ONE

LOOKING FOR ANCIENT EGYPT |

In the early twenty-first century we owe many of our ideas about memory – and the apparent loss of memory – to the centuryold work of Sigmund Freud. From the consulting room of his flat in Vienna, Freud formulated ideas that would lead to a significant shift in thinking about the human mind. Freud proposed that the mind divided into conscious and unconscious operations. In the unconscious, memories of the past lie buried, not so much forgotten as suppressed. They motivate our actions, urges and fears in the present, often in unhelpful ways that could only be overcome by analysing these buried drives. ‘Buried’ is an apt word here, because Freud also had a lifelong passion for archaeology – and that same consulting room was full of images and antiquities from ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt.1 Patients like the poet H. D. reclined on the famous couch beneath a photogravure depicting the temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel by moonlight. On Freud’s desk stood almost three dozen statuettes from ancient cultures, most of which were cast bronze or carved stone images of ancient Egyptian gods – like the baboon of Thoth, god of wisdom, writing and record-keeping. Freud’s housekeeper recalled that he often stroked the smooth head of the stone baboon, like a favourite pet.

For a book on Egypt in a series called ‘Lost Civilizations’, the life and work of Sigmund Freud may seem like a surprising place to start. Freud’s ideas, however, invite us to question how memories are ‘lost’ not only in individual humans, but in human society at large. Many academics, philosophers and writers throughout the twentieth century have explored the idea of a cultural memory that informs the values, structures and daily life of different nations or societies over time.2 In the United States, for instance, cultural memory could be said to include national celebrations such as Thanksgiving; the canon of American literature, art and architecture, and music; and the horrific experience – and long legacy – of slavery. None of these three is a straightforward memory, given the time that has elapsed and the shared, social way in which cultural memory is held. To take each example in turn, Thanksgiving is a holiday that was created by President Lincoln in 1863 to promote unity during the Civil War, although many Americans assume that it can be traced back to seventeenth-century colonists in New England. As for a ‘canon’ of the arts, what belongs in or out of any canon is a source of sometimes heated debate. And slavery is pointedly not remembered by American institutions: until the opening of the National Museum of African American Art and Culture in 2016, there was no museum, no memorial, no official recognition at state or national level of the millions who died or endured lives of crippling degradation due to slavery – nor any open acknowledgement of the ongoing impact its slave-owning past has on American society today.

Here is where Freud’s theories have seemed to offer insight into the social psyche as well as the individual human mind: buried memories may be suppressing a traumatic event (like slavery), glossing over a history of European colonial incursion, or simply ignoring works that do not easily fit the dominant cultural narrative. Anxiety concentrates around these memories, which are lost but not forgotten. When some trigger – white police shooting unarmed black men, for instance – touches on a painful memory like pressure on a bruise, the trauma reasserts itself in another guise.

If some cultural memories appear to bury difficult histories, what about the shared histories and memories that we seem to celebrate, even revel in? In mainstream Western culture, ancient Egypt often takes this positive role, playing the part of a long-lost civilization that we – the West (problematic as this simplified term is) – have incorporated into our own history and identity. We ‘discovered’ it, as dozens of books, television shows and museum displays like to put it. And we actively remember it in ways that range from the patriotic, such as the obelisk that dominates the Place de la Concorde in Paris (where the guillotine once stood),3 to the bombastic, of which the pyramid-shaped Luxor hotel and casino in Las Vegas is just one example.

Stone baboon owned by Sigmund Freud, made in Egypt or Italy around the 1st century AD.

Sites of Ancient Egypt.

Is the casino a bit of harmless fun, and is the obelisk merely part of the noble cause of Western science, saving and studying the ancient past for humanity’s common good? As this book will show, things are never quite so simple when we try to remember a lost civilization. We will return to France’s claims on Egypt later in this book, and to the Las Vegas hotel right at the end, but let us first return to Freud, whose archaeology of the human mind was carried out in tandem with the archaeological discoveries of his day, which Freud followed with an amateur’s keen interest. Although he used ancient Greek mythology to characterize his theories and never visited archaeological sites farther from Vienna than Athens and Rome, it was Egypt that occupied his thoughts in later life and Egypt that confronted him as he sat at his desk, face to face with the gods.

Man in the Moon

The baboon still stands in its usual place near the right-hand corner of Freud’s desk, arranged in the north London home where he spent the last year of his life, a refugee from Nazi-occupied Vienna. Preserved as the Freud Museum, the house contains the library, antiquities and rug collection (as well as the famous analytic couch) that Freud brought with him in 1938, recreating his familiar surroundings as much as possible in exile. His friend and former patient, Marie Napoléon, paid the tax levy required by the Nazi authorities for all Jewish property taken out of Austria.

Around 21.5 cm (8 in.) high, the statuette represents a male baboon sitting on its haunches, its tail wrapped around its right side and its forepaws on its knees. On its head, a round blob represents the disc of a full moon resting on top of a crescent moon. Although Egyptian in style and subject matter – the baboon was one of two animals identified with Thoth – Freud’s figure was probably made in Rome or else in Egypt when it was under Roman imperial rule, from the late first century BC to the third century AD. It is carved from a single piece of marble, a stone rarely found in Egypt but common in Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. The circular base is not typical for Egyptian-style sculpture, which preferred rectangular bases for statues. That, and the fact that the baboon’s back paws and the end of its tail have been re-worked where they meet the edge, suggests the Freud baboon has a complex history. It may have been re-carved in modern times from a damaged ancient piece, in order to make it more attractive to someone like Freud, who bought most of his antiquities from the dealer Robert Lustig, owner of a shop near Freud’s apartment in Vienna. Egypt and other parts of North Africa and the Middle East had few restrictions on the export of antiquities in the early twentieth century. This meant that there was a steady flow of objects to Europe and beyond – especially small, portable objects that could fit easily into a domestic interior like Freud’s. In central Cairo, the new Museum of Egyptian Antiquities that opened in 1902 even had a saleroom where antiquities considered too similar to objects already in the collection, or not important enough, could be bought by members of the public, complete with the required export licence.

The arrangement of figures on Freud’s desk suggests he had purposely selected objects that represented ancient learning and wisdom. A highly educated doctor and prolific writer himself, perhaps he looked to figures like the baboon of Thoth, the Greek goddess Athena or the Egyptian wise man Imhotep for inspiration while he worked. In Egyptian mythology Thoth was the god of writing and wisdom. We could argue that Thoth had power over cultural memory and history as well, because as the sacred scribe, it was Thoth who recorded in writing all the key decisions, dates and events that the king and the gods required. He wrote down the outcome of the ‘weighing of the heart’ that judged the dead, and he inscribed the number of years allotted to a king’s reign on the sacred persea-tree. Writing mattered in ancient Egypt, where only between 2 and 5 per cent of the populace could read and write. In a population that averaged perhaps 2 million at its height, that amounts to some 40,000 individuals, almost all of them men and boys trained in scribal schools attached to temples. Temples were not just places of ritual and worship: they were the backbone of the Egyptian state and economy. Learning to read and write equipped selected boys for work as scribes, a role that could gain them respect, authority and eventually even a place high up in the country’s administration. Boys learned to write by copying out tales with a moralizing bent. One of these school texts advised students, ‘love writing more than your mother . . . recognize its beauty, for being a scribe is greater than any profession, and there is nothing else like it on earth.’4

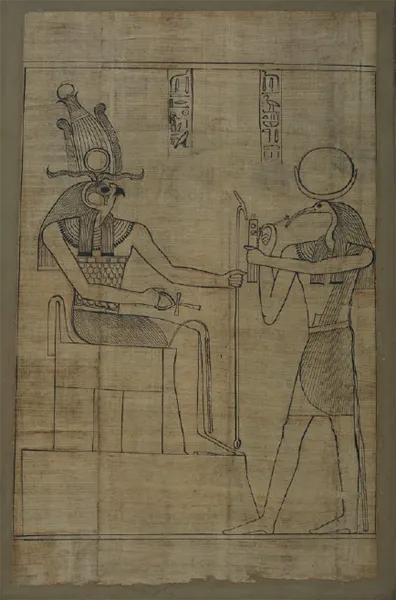

His own role as a scribe explains why Thoth often appears in art holding a reed pen, a roll of papyrus and a narrow case to store spare pens and the two ink pots – one black, one red – that every writer needed. Instead of a baboon, Thoth could appear as an African sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus, a wading bird with a thin, curved beak) or, in scenes with other gods, as a human with a healthy male body and an ibis head, supporting the familiar full and crescent moons. This is how he appears in a scene from the Book of the Dead papyrus of the well-to-do priestess Nestanebtasheru (c. 950 BC), which shows Thoth dipping his pen into ink before the falcon-headed god Re-Horakhty.5 Originally more than 37 metres (121 ft) long, the papyrus was cut into pieces and sandwiched between sheets of glass to help preserve and display it in the British Museum; in antiquity, it formed a thick roll designed to be placed in the priestess’s burial. Its hieroglyphic texts take the form of magical spells to help her navigate the underworld. Many of these spells may parallel the arcane wisdom, cult secrets, and entrance or initiation tests that were part of a priest’s – or priestess’s – working life. Being a priest or priestess brought these individuals into contact with a divine world so powerful that they had to be equipped to deal with it, and in addition to recording the spells and rites they needed, a papyrus like this one represented that other world in all its splendour. Even in black ink on the pure, golden-white papyrus, the lunar disc of Thoth and the sun-disc on the crown of Re-Horakhty represent the light emitted by these heavenly bodies, while the gods’ long, streaming hair (what Egyptologists call a three-part, or ‘tripartite’, wig or headdress) associated them with shining blue skies and rare lapis lazuli. Gods shimmered like gleaming metal and emanated multicoloured sunlight. In Egyptian art, the fact that they are so often made up of human and animal parts – not only their bodies and heads, but the bull tails, bird feathers and animal horns they wear – does not indicate that ancient Egyptians imagined their gods looked like this. These were artistic conventions for showing what could scarcely be imagined, taking elements from the natural world to help picture the ungraspable enormity of the divine.

The gods Re-Horakhty and Thoth, ink drawing on papyrus, from the Book of the Dead made for the priestess Nestanebtasheru, c. 950 BC.

For a god as significant and as versatile as Thoth, Egyptian artistic conventions meant that his ibis, ibis-headed human and baboon forms all represented ‘Thoth’, but suited different purposes. Small figures of ibises were popular dedications to Thoth in some periods of Egyptian history, while figures of Thoth as a baboon range from statuettes like Freud’s, to tiny amulets, to large, free-standing statues arranged in temple complexes. The animals associated with specific gods were also bred to be sacrificed, mummified and buried as devotional offerings; this practice was widespread from around 600 BC into the Roman period.6 Near the site of the largest temple of Thoth in Egypt, archaeologists have discovered thousands of mummified ibises and baboons, neatly stacked in catacombs near the human cemetery that served the town.7 As the god of Egyptian writing and wisdom, Thoth and his cults may have held particular appeal at a time when Egypt came increasingly into contact – and sometimes conflict – with the Assyrian Empire, Greek merchants and mercenaries, and eventually the Roman Empire. With the succession of Egyptian kings disrupted, temples and their priests offered some sense of stability, and Thoth, the gods’ own scribe, symbolized a potent mix of writing and wisdom that was increasingly restricted to the literate few who knew the Egyptian scripts and languages. Priests could use their temples as repositories of ancient, secret knowledge while the world around them changed – a strategy that proved to be a success, since it was through the figure of the god Thoth that the classical and medieval worlds remembered the distant past of pharaonic Egypt.

Hermes on the hush

The temple of Thoth, with its vast cemetery of sacred animal mummies, lies on the west bank of the Nile in the province of Al Minya, some 300 km (185 miles) south of Cairo. The names of the archaeological site and adjacent town confirm the long, multilayered history of ancient Egypt, creating a palimpsest – faint traces of the past that can be glimpsed beneath the modern surface, like erasures that have been written over on a reused piece of parchment. The name of the local town is el-Ashmunein, an Arabic version of an earlier Coptic name, Shmunein, which itself derives from the ancient Egyptian name Khmunu, ‘City of the Eight’. In early Egyptian religion, one creation myth held that four pairs of gods, known collectively as ‘The Eight’, brought the ordered world out of its primeval, watery chaos. Later, as the worship of Thoth became more important in the town, his sacred ibis was added to some versions of the myth. Although gods like Thoth were worshipped throughout Egypt, one of his most important temples was at Khmunu, though hardly any traces of this vast structure survive today.

In Egyptian archaeology, which often uses older place names to refer to ancient sites, el-Ashmunein is better known as Hermopolis, meaning ‘city of Hermes’ in Greek. As Greek-speaking people from around the eastern Mediterranean began to travel to Egypt for trade, and eventually came to settle in the country after its conquest by Alexander the Great, they drew comparisons between their own gods and the Egyptian gods. This meant that many Egyptian gods could be referred to easily by familiar Greek names, while others – like the Egyptian Aset and Wesir – were given Greekstyle names that we still use (Isis and Osiris in this instance). Today, we most often think of Hermes as the messenger of the Greek gods, equipped with wings to give him speed. But in antiquity Hermes was equally considered a god of language, writing and learning, known for his wit and his wiles. Identifying Hermes with Thoth made linguistic and theological sense, and it was the name Hermopolis that stuck in the imagination of early European visitors, scholars and archaeologists (or Hermopolis Magna, ‘The Great’, to distinguish it from a smaller Egyptian town of the same name).

It was not only Greeks visiting or living in Egypt who took an interest in Egyptian religion. Extensive trade links throughout the eastern Mediterranean – the coasts of Egypt, the Levant and Turkey; the islands of Cyprus, Crete and the Aegean Sea; and the Italian peninsula – had been facilitated by Greek and Phoenician (from Lebanon) sailors for many years. Small Egyptian cult centres flourished from at least the second century BC, and probably earlier, into the Roman Empire. The religion practised in the Mediterranean centred on the goddess Isis, the sister-wife of the mythical king Osiris, who used her powerful magic to restore his life force (and sexual potency) after his brother Seth murdered him. Isis was an all-powerful mother figu...