![]()

In Civilisation, Kenneth Clark’s study of Western civilization based on his pioneering 1960s television series, the eminent art historian pondered the non-Western origins of civilization two-and-a-half millennia before the classical Greeks. He observed:

three or four times in history man has made a leap forward that would have been unthinkable under ordinary evolutionary conditions. One such time was about the year 3000 BC, when quite suddenly civilisation appeared, not only in Egypt and Mesopotamia but also in the Indus valley; another was in the sixth century BC, when there was not only the miracle of Ionia and Greece – philosophy, science, art, poetry, all reaching a point that wasn’t reached again for two thousand years – but also in India a spiritual enlightenment that has perhaps never been equalled.1

Ancient Egypt and ancient Mesopotamia are familiar to the world, because of their art, architecture and royal burials; their extensive texts written in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian and Babylonian cuneiform; and numerous references to the Egyptian pharaohs and Babylonian and Persian rulers in the Hebrew Bible and Greek and Roman literature. So, too, are the glories of classical Greece and, maybe less so, the spirituality of Buddhist India (roughly contemporary with Greek philosophy) and early Hindu India as expressed in the Vedic literature (probably composed between 1500 and 500 BC). Not so familiar, however, is the civilization that appeared in the Indus valley – in what is now Pakistan and India – during the first half of the third millennium BC.

The Indus civilization was, in its own way, as extraordinary as the civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia. But it declined around the nineteenth century BC and left no direct legacy in the Indian subcontinent. Neither Alexander the Great, who invaded India from the northwest in the fourth century BC, nor Asoka Maurya, the great Buddhist-oriented emperor who ruled most of the subcontinent in the third century BC, was even dimly aware of the Indus civilization; nor were the Arab, Mughal and European colonial rulers of India during the next two millennia. Indeed, amazing as it may seem, the Indus civilization remained altogether invisible until the 1920s, when it was almost accidentally discovered at Harappa in the Punjab by British and Indian archaeologists (during Clark’s youth). Ever since then, scholars have been trying to elucidate its mysteries, including the meanings encoded in the characters of its aesthetically exquisite but stubbornly undeciphered writing system, and thereby to elevate this most significant of ‘lost’ civilizations to the position it deserves – both in the history of South Asia and in world history.

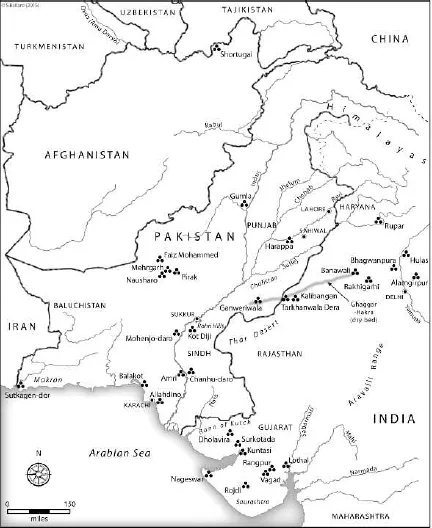

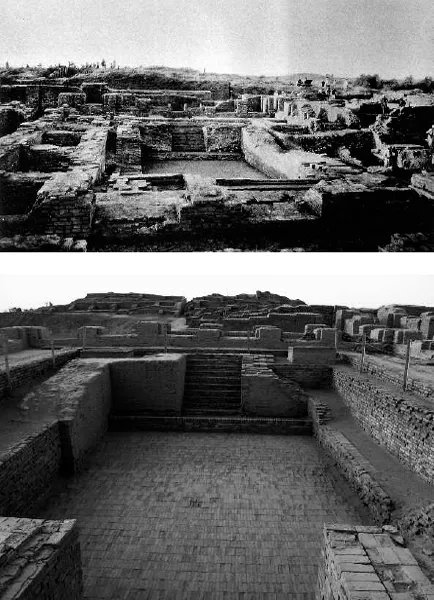

Mohenjo-daro, one of two leading cities of the Indus civilization along with Harappa, seen from the air. It is located in southern Pakistan near the Indus river.

Map showing the most important of the approximately 1,000 sites of the Indus civilization and adjacent areas. Most sites belong to the Mature period, c. 2600–1900 BC, but some are older, in one case as early as 7000 BC.

The Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro.

Archaeologists have identified well over a thousand settlements belonging to the Indus civilization in its various phases. They cover at least 800,000 square kilometres of what in 1947 became Pakistan and India – an area approximately a quarter the size of Western Europe – with an original population of perhaps one million people (the same as that of ancient Rome at its height). This was the most extensive urban culture of its time, about twice the size of its equivalent in Egypt or Mesopotamia. Though most Indus settlements were villages, some were towns, and at least five were substantial cities. The two largest cities, Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, located some 600 kilometres apart beside the Indus river and one of its many tributaries, were comparable with cities like Memphis in Egypt and Ur in Mesopotamia during the ‘Mature’ period of the Indus civilization, that is, between about 2600 and 1900 BC. Their maximum populations probably never exceeded 50,000, although life expectancy was good, judging from human bones in the cemetery at Harappa: nearly half of the individuals reached their mid-30s and almost one-sixth lived beyond the age of 55.

However, the cities, despite their excellent brick-built construction, do not boast pyramids, palaces, temples, graves, statues, paintings or hoards of gold like those found in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Their grandest building is the so-called Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro, the earliest public water tank in the ancient world, a rectangle measuring 12 metres by 7 metres, with two wide staircases to the north and south leading down to a brick floor at a maximum depth of 2.4 metres, made watertight by a thick layer of bitumen. Though technically astonishing for its time, without doubt, the Great Bath was totally unadorned by carving or painting, so far as archaeologists can tell.

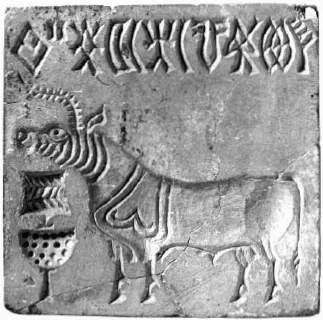

Yet Indus society, fed by crops watered by the great river and its many tributaries flowing from the Himalayas, was remarkably productive and sophisticated in other ways. For example, the Indus dwellers constructed ocean-going merchant ships that sailed as far as the Persian Gulf and the river-based cities of Mesopotamia, where Indus-made jewellery, weights, inscribed seals and other objects have been excavated, dating back to around 2500 BC. Mesopotamian cuneiform inscriptions refer to the Indus region by the name Meluhha, the precise meaning of which is unknown. The Indus cities’ drainage and sanitation were two millennia ahead of those of the Roman empire; besides the Great Bath, they included magnificent circular wells, elaborate drains running beneath corbelled arches and the world’s first toilets. The cities’ well-planned streets, generally laid out in the cardinal directions, put to shame all but the town planning of the twentieth century AD. Some of their many personal ornaments, such as the necklaces of finely drilled, biconical carnelian beads up to 13 centimetres in length found in the royal cemetery of Ur in Mesopotamia, rival the treasures of the Egyptian pharaohs. Their binary/decimal system of standardized weights – consisting of stone cubes and truncated spheres – is unique in the ancient world, suggesting a highly developed economy. And the partially pictographic characters and vivid animal and human motifs of the tantalizing Indus script, inscribed on small seal stones and terracotta tablets, occasionally on metal, form ‘little masterpieces of controlled realism, with a monumental strength in one sense out of all proportion to their size and in another entirely related to it’, enthused the best-known excavator of the Indus civilization, Mortimer Wheeler.2 Once seen, the seal stones are never forgotten – as witness the more than 100 differing decipherments of the Indus script proffered since the 1920s, some of them by distinguished academics such as the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (not to mention many amateurs and cranks).

Indus archaeology has come a long way in almost a century. Nonetheless, it throws up many more unanswered fundamental questions than the archaeology of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (and China). A ‘great cloud of unknowns . . . hangs over the civilisation’, noted an Indus scholar, Jane McIntosh, in 2002.3 Moreover, although excavation continues in both Pakistan and India, less than 10 per cent of the just over 1,000 Mature-period settlements have been excavated. Important clues, including further inscriptions, unquestionably remain to be dug up, as has happened in the past two or three decades. But, given the already extensive excavation of the cities, it does not seem likely that new discoveries will solve all of the current questions about the Indus civilization. Therefore this book, like all books on the subject, must mix hard information from archaeology with informed speculation in trying to answer these questions.

| Indus seal stone showing a ‘unicorn’, a ritual offering stand and signs, made of steatite, from Mohenjo-daro. The writing system is yet to be deciphered. |

In particular, was the civilization an indigenous development, apparently emerging from neighbouring Baluchistan, where there is ample evidence for village settlement at Mehrgarh as early as 7000 BC? Or was it stimulated by the growth of civilization in not-so-distant Mesopotamia during the fourth millennium BC? What type of authority held together such an evidently organized, uniform and widespread society, if it truly did manage to prosper without palaces, royal graves, temples, powerful rulers and even priests? Why does the Indus civilization offer no definitive evidence for warfare, in the form of defensive fortifications, metal weapons and warriors – a situation without parallel in war-addicted ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt and China, not to mention all subsequent civilizations? Was the Indus religion the origin of Hinduism? Or is the apparent resemblance of some Indus seal iconography and practices to much later Hindu iconography and practices, such as the worship of the god Shiva and the caste system, based on wishful thinking? Is the Indus language that is written in the undeciphered script (assuming only a single written Indus language) related to still-existing Indian languages, such as the Dravidian languages of south India or the Sanskritic languages of north India? Lastly, why did the Indus civilization decline after about 1900 BC, and why did it leave no trace in the historical record? The characters of the Indus script seem to have become indecipherable almost four thousand years ago with the civilization’s decline. They certainly bear no resemblance to the next writing that appeared in India, after an enormous gap of a millennium and a half: the Brahmi and Kharosthi alphabetic scripts used to write the rock and pillar inscriptions of the emperor Asoka in the third century BC, which were modelled on an alphabetic script from West Asia.

Scores of archaeologists and linguists – from Europe, India and Pakistan, Japan, Russia and the United States – have suggested answers to these fascinating questions. But inevitably they have been obliged to speculate; there can be no overall consensus, for lack of sufficient archaeological evidence and because the Indus script is mute.

To complicate matters, some of the debates have acquired a partisan political edge. The discovery of the Indus civilization understandably promoted national pride during India’s movement towards independence from British rule in the 1930s and ’40s. Its first excavator, John Marshall, started the trend in 1931 by claiming that ‘the religion of the Indus peoples . . . is so characteristically Indian as hardly to be distinguishable from living Hinduism.’4 The Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehru, before he became prime minister of independent India, noted, reasonably enough: ‘It is surprising how much there is in Mohenjo-daro and Harappa which reminds one of persisting traditions and habits – popular ritual, craftsmanship, even some fashions in dress.’5 Since then, however, and especially since the 1980s, Hindu nationalists in India have gone much further, disregarding archaeological and linguistic evidence in support of an openly political agenda. They are keen to recruit the Indus civilization as the fons et origo of Indian civilization, untainted by outside influence. According to them, it was the originator of the language of the Vedic literature, Sanskrit. This they view as an indigenous language, rather than as one descendant among many languages of a proto-Indo-European language that originated in the Pontic-Caspian steppes of southern Russia during the fourth millennium BC and reached India in the second millennium BC via Indo-Aryan-speaking migrants from Central Asia – the dominant view among non-Indian scholars regarding the origin of Sanskrit. They also view the Indus civilization as the originator of an early form of Hinduism. Thus, the Hindu nationalists promote the Indus civilization as the source of a continuous Indian identity dating back more than five millennia.

In the late 1990s certain Indian historians wishing to rewrite school textbooks at the behest of India’s new Hindu nationalist government, appealed to a new book, The Deciphered Indus Script, written by two Indians with some linguistic and scientific credentials. Its authors, N. Jha and N. S. Rajaram, made astounding claims, announced to the Indian press in 1999 and published in 2000. The Indus script was said to be even older than had been thought (the mid-third millennium BC), dating back to the mid-fourth millennium BC, making it the world’s oldest readable writing, pre-dating Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs. It apparently employed some kind of alphabet, two millennia older than the world’s earliest-known alphabets from the Near East. Perhaps most sensational of all, at least for Indians, the Indus inscriptions were supposedly written in Vedic Sanskrit; one of them was found to mention a crucial Vedic river, the Saraswati, albeit obliquely (‘Ila surrounds the blessed land’).6 This river, highly revered in the Rigveda, is today not visible above ground as a single stream, but is nevertheless known from ground surveys to have been a major river during the Indus civilization. Surveys on the Pakistani side of the India/Pakistan desert border region conducted in the 1970s and after have traced much, though not all, of the Saraswati’s former course, part of which flowed in parallel with the Indus rather than as its tributary. In the course of their surveying, archaeologists (led by Mohammed Rafique Mughal) stumbled upon close to two hundred settlements from the Mature period of the Indus civilization clustering along the ancient course of the Saraswati (almost all of which, including a city, Ganweriwala, await excavation).

Providential further support for the Hindu nationalist view seemed to come in the form of an excavation photograph from the 1920s showing a broken Indus seal inscription depicting the hindquarters of an animal, accompanied by four characters. Jha and Rajaram claimed that the animal was a horse, as shown in a ‘computer-enhanced’ drawing published by them; and that the four characters could be read, in Vedic Sanskrit, as ‘arko ha as va’, which they translated as ‘Sun indeed like the horse’.7 The authors translated another Indus inscription, which was discovered in 1990 in Gujarat and is generally regarded as some kind of monumental signboard, as: ‘I was a...