![]()

1

FROM ABRAHAM’S JOURNEYS

TO THE SIX-DAY WAR

Current events in the Middle East can best be understood if we start with a brief review of the history of the region. Since I was a little child, I have been familiar with the journey of Abraham from Ur through Haran to Canaan about 2000 B.C., the Israelites’ enslavement in Egypt about five hundred years later, the powerful rule of Kings David and Solomon about 1000 B.C., the later captivity of the Hebrews by the Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians, and their return from exile to rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple about five hundred years before the birth of Jesus Christ. My father and others taught me every Sunday about the other great prophets who relayed God’s word to his chosen people, mostly during the period of their exile, and who Christians believe were preparing for the coming of the Messiah, Jesus Christ, a descendant of David.

The Greeks conquered the region three centuries before the earthly ministry of Jesus, and the Jews established an independent Judea that existed until the Roman conquerors came about fifty years later. They ruled with a firm hand, insisting on the maintenance of peace and the proper payment of taxes. There was a Jewish revolt in A.D. 70, which was crushed by the Romans, who destroyed the Temple. After another revolt in A.D. 134, many Jews were forced into exile, and the Romans named its province Syria-Palaestina while the Jews preferred that it be called Eretz Israel.

A few churches were formed by early Christians from Jerusalem and struggled for survival around the Mediterranean coast to Rome. After Emperor Constantine was converted to Christianity, circa A.D. 325, the powerful leader imposed his religious beliefs throughout the kingdom. This Christian advantage in the region was largely overcome after the Prophet Muhammad (570–632) founded the Islamic faith and united the Arabian Peninsula, and his followers spread their political domination and religion throughout Syria-Palestine, Persia, Egypt, North Africa, and southern Europe. Christian crusaders launched massive military crusades to retake Jerusalem and established dominion over Palestine in 1099. However, Saladin, sultan of Egypt, retook the Holy City in 1187, and, after 1291, Muslims controlled Palestine until the end of World War I. Then the French and British played major roles in the Middle East and spread their influence as spoils of victory.

Great Britain issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, promising a Jewish national home in Palestine, with respect for the rights of non-Jewish Palestinians. In 1922, the League of Nations confirmed a British Mandate over Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan, and a French Mandate over Syria and Lebanon. Transjordan became an autonomous kingdom. Later, Palestinian Arabs demanded a halt to Jewish immigration and a ban on land sales to Jews, and in 1939 Britain announced severe restrictions on the Zionist movement and land purchases in Palestine. Violence erupted from Jewish militants, some led by Menachem Begin, the future prime minister of Israel.

It is impossible to comprehend the enormity of the unspeakable crime against humanity—the Holocaust perpetrated by Adolf Hitler—but I studied the superb works of Elie Wiesel and other survivors early in my political career to learn as much as possible about it. More recently, in an intriguing book, The Invisible Wall, my secretary of treasury Michael Blumenthal described the experiences of Jews in Germany based on his own life and those of members of his family, beginning in 1640. Mike was born in Germany in 1926 and escaped the Nazis as a teenager by moving with his family and other Jews to a ghetto in Shanghai in 1939 after his father escaped from the Nazi prison at Buchenwald. Eight years later the Blumenthals were able to come to the United States.

When Hitler became chancellor of the Third Reich, in 1933, Mike wrote:

Germany’s Jews had made an astonishing impact on Germany in many fields and far beyond the country’s borders, but there had never been more than about 600,000 of them—a tiny minority of no more than one percent of the German people. During the first eight years after Hitler seized power, more than 300,000 managed to flee and some 70,000 died; since the Jewish population was over-aged, the rate of deaths greatly exceeded that of births. So, when the doors finally closed in 1941 and escape was no longer possible, there were only 163,000 Jews left. Most were deported to the East, and very few survived. Thousands took their own lives.

In 1947, Britain decided to let the United Nations determine what to do about Palestine, which was partitioned between Jews and Arabs, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem as international areas. By this time, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Transjordan were independent states.

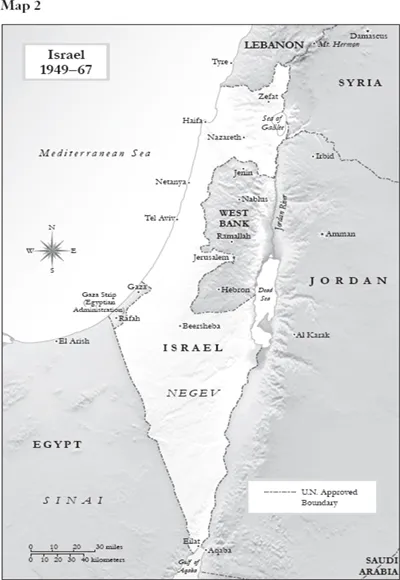

A year later the British Mandate over Palestine terminated and the State of Israel was proclaimed. The troops of all the surrounding countries—Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon— attacked the tiny new nation that had no regular army, and were joined by Iraqis and other Arabs. Fighting for their lives and their nation, Israelis finally prevailed after a year of conflict, and a cease-fire was negotiated with expanded Israeli territory (about 77 percent of the total) accepted by the Arab adversaries. The armistice line became known as the “Green Line,” accepted by Israel and confirmed as legal by the international community. Jordan annexed East Jerusalem and the area between Israel and the Jordan River (about 22 percent), and Egypt assumed control over the Gaza Strip (about one percent).

The United Nations estimates that about 710,000 Arabs left voluntarily or were ejected from Israel, and troops then barred their return and razed more than five hundred of their ancestral villages. This became known by the Arabs as the naqba, or catastrophe, and U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194 established a conciliation commission and asserted that refugees wishing to return to their homes and live in peace should be allowed to do so, that compensation should be paid to others, and that free access to the holy places should be assured. The treatment of these refugees and their descendants has remained a major source of dispute.

In 1956, Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal, and Israel, Britain, and France occupied the canal area. Pressure from the international community forced all foreign troops to withdraw from Egyptian territories by the next year, and U.N. forces were assigned to patrol strategic areas of the Sinai Peninsula.

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was established in 1964, committed to liberating the homeland of the Palestinian people.

In May 1967, Egypt expelled the U.N. monitoring force from the Sinai, moved a strong military force to the border, closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, and signed a mutual defense treaty with Jordan and Syria. Israel responded by launching a preemptive attack that destroyed Egypt’s air force. When Jordan and Syria joined in the combat, Israel gained control within six days of the Sinai, the Golan Heights, Gaza, and the West Bank including East Jerusalem.

Six months later, U.N. Security Council Resolution 242 was passed, confirming the inadmissibility of the acquisition of land by force and calling for Israel’s withdrawal from occupied territories, the right of all states in the region to live in peace within secure and recognized borders, and a just solution to the refugee problem (see Appendix 1).

![]()

2

MY EARLY INVOLVEMENT

WITH ISRAEL

While I was governor of Georgia, in 1973, I traveled with my wife, Rosalynn, throughout Israel and the occupied territories as guests of Prime Minister Golda Meir and General Yitzhak Rabin, hero of the Six-Day War. We visited the usual tourist spots and Christian holy places but, more important, several kibbutzim, including a relatively new one on the escarpment of the Golan Heights. We enjoyed extensive discussions with these early Jewish settlers and learned that there were about fifteen hundred of them living on occupied Arab land at that time. The general presumption among Israeli leaders was that the settlers would withdraw as other provisions of U.N. Resolution 242 were honored. During the more official portion of our visit we rode torpedo boats at Haifa and participated in a graduation ceremony for young soldiers at Bethel, and I had detailed “secret” briefings from Israeli intelligence chief General Chaim Bar-Lev, General Rabin, Prime Minister Meir, and one of the world’s most eloquent diplomats, Abba Eban.

This visit to the Holy Land made a lasting impression on me. I had taught Bible lessons on Sundays since I was a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy, divided equally between Hebrew scriptures and the New Testament. Like almost all other American Christians, I believed that Jewish survivors of the Holocaust deserved their own nation and had the right to live peacefully with their neighbors. This homeland for the Jews was compatible with the teachings of the Bible. These beliefs gave me an unshakable commitment to the security and peaceful existence of Israel.

I was making plans to run for president during the year of our visit to Israel, and I began a detailed study of political developments in the region. The most significant event during 1973 was the apparent expulsion by Egypt of Soviet advisers, based on a public allegation by President Anwar Sadat that their benefactor refused to provide the advanced weapons needed for Egypt’s defense. In fact, most Soviet military experts were simply redeployed to Syria, with the consent of the Egyptian government, while the two nations began to plan an attack on Israel.

In October 1973 (during the Yom Kippur holidays), Israeli forces were struck simultaneously in the Sinai and the Golan Heights, catching Prime Minister Golda Meir and her government by surprise. After sixteen days of intense combat, various disengagement agreements followed, negotiated mostly by U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger. U.N. Security Council Resolution 338 was passed, confirming Resolution 242 and calling for international peace talks, likely sponsored primarily by the United States and the Soviet Union. Although Arab military attacks were successfully repulsed, this ended the euphoria in Israel following its victory in the Six-Day War of 1967 and restored the pride and confidence of Egypt and Syria. General Rabin replaced Meir as Israel’s prime minister while other events were shaping the situation I would inherit as president.

In 1974, the Arab summit at Rabat proclaimed the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, who were scattered throughout the region. This was soon followed by a public pledge from the U.S. government to have no contacts with leaders of the PLO until they adopted U.N. Resolution 242 and acknowledged Israel’s right to exist in peace. When civil war erupted in Lebanon in 1975, the international community, including the United States, approved Syria’s sending troops into the troubled country to establish order. In June 1976, our ambassador to Lebanon was kidnapped and murdered, his successor was forced to return to Washington, and American nationals had to be evacuated from the country by sea.

• • •

Except for our tour of the Holy Land when I was governor, I was not directly involved in affairs of the Middle East, but the region was of great interest to me and I probed for new ideas. At a 1975 meeting of the Trilateral Commission* in Japan, I made some impromptu comments advocating balanced and much more aggressive steps toward peace. Afterward, the commission’s executive director, Zbigniew Brzezinski, came and offered to help me develop my ideas. A year later, during my campaign for president, he and Stu Eizenstat assisted me in preparing my basic speech about the Middle East, which I first delivered in an Orthodox synagogue in Elizabeth, New Jersey. (I remember that it was near a shipyard where some of our nation’s submarines had been built.) Wearing a blue yarmulke, I said:

The land of Israel has always meant a great deal to me. As a boy I read of the prophets and martyrs in the Bible—the same Bible that we all study together. As an American I have admired the State of Israel and how she, like the United States, opened her doors to the homeless and the oppressed.... All people of goodwill can agree it is time—it is far past time—for permanent peace in the Middle East.... A real peace must be based on absolute assurance of Israel’s survival and security. As President, I would never yield on that point. The survival of Israel is not just a political issue, it is a moral imperative.

Although President Gerald Ford was known as a friend of Israel, neither he nor his predecessors had considered a strong move toward a comprehensive peace agreement. Instead of the gradualist approach being pursued by him and Secretary of State Kissinger, I argued during the general election campaign that “a limited settlement, as we have seen in the past, still leaves unresolved the underlying threat to Israel. A comprehensive settlement is needed—one that will end the conflict between Israel and its neighbors once and for all.” In this same speech, I went on to say, “There is a humanitarian core within the complexities of the Palestinian problem. Too many human beings, denied a sense of hope for the future, are living in makeshift and crowded camps where demagogues and terrorists can feed on their despair.”

I continued this theme with a number of audiences, but my more comprehensive approach, including Palestinian rights, received little attention from the news media. During the second of our three presidential debates, in October, I pushed hard on the Middle East issue, including the Arab boycott. One of Ford’s strong supporters, Rita Hauser, commented two years later, “It was astounding to me that Carter made so much in that second debate of what I will call the Jewish issues.... I think it made a great difference because the Jews were very puzzled by Carter—to this day they remain puzzled by Carter—and he was not a man to whom there would be a natural attraction.”

It was well known among my White House staff and cabinet officers even before inauguration day that peace in the Middle East would be at the top of my foreign affairs agenda for prompt action. Looking back on my presidency and the succeeding years, I believe the most important single mission in my political life has been to assist in bringing peace to Israel and its neighbors and to promote human rights. I didn’t have an adequate comprehension in my earlier political days that an almost inevitable conflict would evolve between the two as I dealt with Israelis and Palestinians. Once in office, I lost no time in beginning this work.

The issue of Middle East peace was fairly dormant in January 1977, but many of my inherited duties were directly and adversely affected by events in the troubled region. There had been four major wars during the preceding twenty-five years led or supported by Egypt, the only Arab country (with Soviet military backing) that had the status of a formidable challenger. Also, Jews in the Soviet Union were singled out for persecution, and only in rare cases were they permitted to emigrate to Europe, the United States, or other free nations. There was a lack of any concerted effort by our government to bring peace to America’s closest ally in the Middle East, and, in fact, there were no demands on me as a successful candidate to initiate such negotiations. Having visited the Holocaust museum Yad Vashem on my visit to Israel, I was aware that there had never been any memorial site in America as a reminder of the despicable events of the Nazi Holocaust.

An especially reprehensible situation that I faced was the embargo by Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), not only to constrain the distribution of oil to our country but to boycott American businesses that conducted trade with Israel. Amazingly, our government was acquiescent and many business leaders had signed agreements to comply with this obnoxious restraint. In my second debate with President Ford during our general election campaign, I had stated, “I believe that the boycott of American businesses by the Arab countries because those businesses trade with Israel is an absolute disgrace. This is the first time that I remember, in the history of our country, when we’ve let a foreign country circumvent or change our B...