![]()

FCT Implementation

![]()

Strategic Alignment

Moving Up and to the Left

The road to becoming a new product development dynamo starts long before any single development begins. Experience clearly demonstrates that the further one moves upstream in thinking, planning, and action, the faster the ultimate speed of the firm is. We call this up-front work strategic alignment because the focus is to ensure that the firm’s purpose, strategy, and structures are aligned to each other in order to minimize any distraction or disruption once development begins. Any misalignment will reduce speed and waste energy in the race against the market clock and the competition.

This chapter will briefly highlight why strategic alignment is critical, who is responsible for ensuring that it occurs, and how to do it. We will use the strategic alignment planning model as an implementation template. This model provides a step-by-step approach for achieving strategic alignment, but it obviously is not the only approach. We offer it as a starting point that we fully expect each reader will tweak and tune to meet his or her specific needs. We will close the chapter by introducing the Core Products case study. For the rest of this book, we will visit with Core Products, Inc., and see how it implemented the FCT concepts. People and products are disguised, but otherwise Core Products provides a real example that will help the reader translate the purity of concept into the pragmatic choices that one must make along the implementation path. Let’s begin with a brief overview of the role of strategic alignment.

Why Strategic Alignment Is Essential for Fast Cycle Time

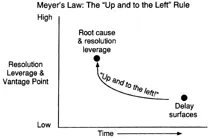

Cycle time delays follow a consistent pattern. Specifically, the root cause of any delay is always upstream of where the delay itself surfaces. Additionally, the best leverage for resolving the delay is from a vantage point higher than where the delay originally surfaces. We’ve seen this phenomenon so often that we call it Meyer’s Law: the “Up and to the Left” rule, because the root cause of any cycle time problem is up and to the left (see Exhibit 5.1).

For example, one of the most common delays in new product development is reaching agreement on product specifications. Yet, what often appears as a delay in setting product “specs” is actually caused by other factors, such as the absence of upstream planning. Let’s examine what happens to a design team’s specification-setting effort when the company lacks an overall product plan.

A product plan defines the company’s target markets and the products they will develop for each market. The product plan establishes high-level product definitions within which design teams detail their product’s specifications. Because the overall product plan integrates individual products into a unified product slate, it should be created from a higher vantage point than that of a single development team. We use the term vantage point because it doesn’t necessarily have to be a higher level organizationally; the task may be done by a corporate product planning or strategic marketing group. The group’s scope of responsibilities enables it to look across products and markets to create a coherent plan. A design team lacks the perspective, data, and frequently the analysis experience required to make these choices.

Within each design team, specification discussions have to resolve trade-offs among time to market, performance, and cost. To do this intelligently, each design team establishes decision criteria. If criteria are established without regard to other products in development, the final specifications could easily overlap or conflict with other products under development. Thus, to develop a specification that is good for the program and the company, the team has to understand where their product fits with other program concepts and priorities. This is normally provided by the high-level definitions within the company’s product plan.

EXHIBIT 5.1

When an overall product plan is missing, each design team is forced to create its own high-level product definition. And because it knows that its product ultimately has to complement other development efforts, it also has to re-create high-level definitions for the other development efforts. The team thus stops setting its own specs and switches to understanding the market targets of the other development efforts. Because it may lack data or perspective, the discussions of other programs are often based purely on opinion.

Knowing it is on shaky ground, the team sees unhelpful behaviors emerge. It can become gun-shy and avoid any issue where there is conflict. It may seek agreement for agreement’s sake and therefore end up with weak specs that cannot stand up to substantive challenge; this invites further delay when the inevitable challenges occur. And because there are no previously agreed-to high-level specs, discussions about feature trade-offs are often unconscious attempts to reverse engineer the missing high-level product definition. In sum, business and product strategy are poorly addressed by essentially the wrong group, and the resulting specs are often weak. And, of course, the whole process is an enormous time sink. We have seen specification setting linger like this for six months or longer.

In this and many situations, the design team’s delay is simply symptomatic of the lack of upstream planing. It would be a mistake to try to fix the design team because of the delay in setting the specs. The effective solution would be to have a product plan established long before any development effort begins. The root cause of the difficulty in setting the specs is thus “up and to the left.” One way to think about this concept is that whenever a development effort has to stop or change direction, senior management should look up (in terms of vantage point) and to the left (in terms of the time line) and ask, “What process or structure should we have put in place that would have prevented this?”

A similar situation often happens when a company examines its product development process for the first time. A common finding is that each development effort tries to do too much invention during the development effort. In response, the companies adopt a strategy wherein they develop “bookshelf technology modules” upstream of the design effort that the design teams figuratively pull off the bookshelf and use in their developments as is or with slight modification. To make this strategy work, one again has to move up and to the left. First, the bookshelf technologies have to be selected. The strategy has the greatest payoff when the bookshelf technologies are leveraged across many products at once. To do this, one has to define future products, timing, and technical resource requirements and assess the technological difficulty required for each module. Each step takes one further up and to the left.

Organizations that do not heed the Up and to the Left rule find themselves living in constant reactive motion. There is no center of gravity to the business. They are driving as fast as possible to define a product when all of a sudden they swerve to address product quality issues, only to brake a moment later to address a competitor’s new product announcement. Once in the reaction mode, it is very difficult to stop, because the behavior itself is so addicting.

Why is it that senior managers don’t devote the required time upstream? Three reasons stand out. First, many senior executives mistakenly believe that FCT is primarily the responsibility of middle management. FCT is considered a tactical rather than a strategic issue. It is true that middle management leads specific new product development efforts, but their ultimate speed is clearly constrained by the degree of strategic alignment.

We like to explain it this way. If one wanted to speed up public transportation in New York City, one could exhort the bus, taxi, and subway drivers all to drive faster, or one could ban all private cars from the city. Obviously, the second choice is where the leverage is, because it changes the fundamental structure of the city’s traffic problem: too many vehicles. Development teams are like vehicles in a city. They can only go as fast as other traffic or road conditions permit. They cannot change the basic structure themselves; only senior management can.

Second, the work required to create strategic alignment is less satisfying than that for resolving operational issues. Most executives got to their position by taking direct action and solving problems. In contrast, creating strategic alignment is more dependent on defining the right question to prevent problems than it is on finding the right answer to solve problems. This cuts against the grain of many executives’ education and experience.

We all like the feeling of accomplishment. A CEO we know once asked his vice presidents why they got so much enjoyment out of fighting fires or, in his words, “killing alligators.” Each day, they proudly reported to their colleagues and families about the various alligator-sized crises that had occurred and how they slew them. Our friend then asked his vice presidents where alligators came from. The vice presidents laughed and told him they came from baby alligators. When the CEO asked why they didn’t kill the babies, they laughed again and said because the babies don’t bite. There is much less innate satisfaction, visibility, and reward for preventing problems that there is in solving problems. Perhaps performance appraisal and interview criteria used when selecting high-level managers should focus on how good they are at preventing problems rather than solving them.

Third, in contrast to the operational problems, strategic issues are essentially wicked in that they have multiple causes and multiple solutions, and there is no immediate way to test if the decision is correct. The time span between setting a strategic direction and learning if it is right often exceeds the executive’s job tenure. In the United States, senior executives and young high-potential managers often change jobs so frequently that they rarely live with the consequences of their actions.

For these reasons, we find that executives grossly underestimate the importance of strategic alignment and overplay the value of downstream product development tactics, such as computer-aided design technologies. While not as easily measurable, either in cost or contribution, strategic alignment creates a context that focuses the organization’s energy and resources. The responsibility for strategic alignment rests with senior management.

A final word before we introduce and demonstrate how to apply the strategic alignment planning model. Although today’s management literature is replete with exhortations to empower people, the issue is more appropriately the elimination of disabling actions.1 People are born fully powered. One only has to spend an hour with a three-year-old to understand that he or she doesn’t need to be empowered! Organizations that lack strategic alignment effectively disable others from acting because there is no contextual basis for people to know if their actions help or hinder the achievement of organization goals. How can one ask people to focus on value-added tasks if one has not defined what is valued added and what isn’t? Any organization leader who seeks to “empower” people should first create a clear strategic context that enables others to use the power with which they were born.

The Strategic Alignment Planning Model

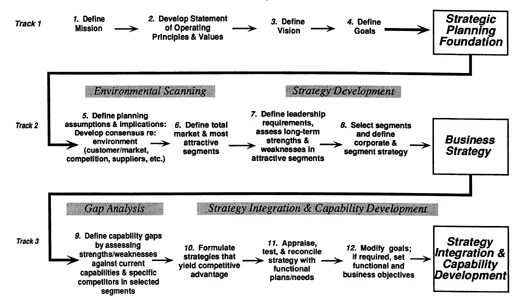

The strategic alignment planning model (Exhibit 5.2) provides a template for defining the key elements in the space that we refer to as “up and to the left.” As it is a template, the reader should fine-tune and emphasize those elements that are most relevant to his or her particular business requirements. The model itself does not attempt to predefine every potential upstream exigency. Rather, it poses the right questions that steer the user to define the most important issues for his or her business. In contrast to other planning models, the strategic alignment model was designed for FCT and therefore emphasizes internal capability development and strategy implementation. We will describe the basic elements of the model and how to use it.2

EXHIBIT 5.2

The model has three horizontal, sequential tracks. The first is the development of the planning foundation. The planning foundation defines the mission, operating principles, visions, and goals for the organization. Combined, these four elements establish the boundaries of the business, define baseline behavior expectations, and set targets and direction. Just as an inadequate building foundation can cripple the growth of a physical structure, a poorly defined planning foundation inhibits the growth of the business. Our experience is that FCT companies keep their planning foundation simple, clear, and openly supportive of FCT philosophies.

The second track defines the firm’s business strategy. This track is probably the most familiar to the reader, as it incorporates many business planning basics. Because of familiarity or urgency, many rush through the planning foundation in order to get to the business strategy “meat” quickly. Our experience suggests that this is unwise. When firms do this, many conversations that are seemingly about markets and products are actually unresolved discussions of mission, vision, goals, or operating principles. The most important element of track two is the environmental scan. This is the one point in the process where attention is focused outside the organization. The scanning process generates a set of planning assumptions about the business environment that, if incorrect, can render the entire process and result worthless.

The final track focuses on strategy implementation and execution. The new strategy is tested against the firm’s capabilities and its original goals. Using gap analysis and gap filling, organizational capability improvements are defined and designed as required. Strategic alignment is only a good intention until it changes core structures, such as resource allocation decisions. The most important aspect of the last track is that it merges strategy with the organization’s annual operating plans and individual functional plans. As a consequence, the strategy becomes part of the daily operating behaviors of people, departments, and functional groups.

Implementing the Strategic Alignment Planning Model

By far, the most important consideration to keep in mind when using the planning model is that the value added is in the planning discussions, not the written plan. The plan itself is an artifact that represents the collective agreement of those involved in the process, but it cannot and should not attempt to ca...