![]()

1 The Problem

![]()

One: Left Behind

When I see those gaps, my heart goes out to the kids. They are our future. I wonder what’s going wrong.

Demetra Skinner, teacher, Hambrick Middle School, Aldine, Texas1

“Are you in the right class?” Roderick Sleet’s teacher asked on the first day of an honors class in a Fort Wayne, Indiana, high school.2 It was a ter-rible question, for which there was no good excuse, but a black student in a demanding course had evidently caught her by surprise. In schools across the country, there are too few black students in honors classes, and too many floundering even in the elementary years. At the Bull Run Ele-mentary School in Fairfax County, Virginia, the fifth- and sixth-graders in a gifted program study geometry and, in the spring of 2002, were read-ing To Kill a Mockingbird. There were no black or Hispanic students in the class.3

This heartbreaking picture reinforces one of America’s worst racial stereotypes: Blacks just aren’t book-smart. As the Introduction made plain, black and Hispanic children are typically academic underachievers, but innate intelligence is not the explanation. In a wonderful Los Angeles class about which we will talk much in Chapters 3 and 4, Latino and Asian children are doing equally well, even though Asian-American children are usually the academic stars. Great teaching makes a huge difference—with all kids.

Before we discuss remedies, however, we must outline the problem. Only if its full magnitude is understood will Americans grasp the need for a radical rethinking of what counts today as educational reform. The shocking facts are a wake-up call. Another generation of black children is drifting through school without acquiring essential skills and knowledge. Hispanic children are not faring much better, and for neither group is there a comforting trend in the direction of progress. Although the current president has put educational reform at the top of his domestic agenda, complacency abounds. We ignore the plight of these youngsters at our peril. As these children fare, so fares the nation.

The Four-Year Skills Gap

This is a book about the racial gap in academic achievement, but how do we actually know how much students are learning? The best evidence comes from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called “the nation’s report card.” Created by Congress in 1969, NAEP regularly tests nationally representative samples of American elementary and secondary school students in the fourth, eighth, and twelfth grades (or sometimes at ages 9, 13, and 17).4

The NAEP results consistently show a frightening gap between the basic academic skills of the average African-American or Latino student and those of the typical white or Asian American.5 By twelfth grade, on average, black students are four years behind those who are white or Asian. Hispanics don’t do much better.

It is important to remember that in every group, of course, some students do well in school, while others flounder. There are plenty of low-performing whites. In fact, they outnumber African Americans and Hispanics, since whites are still more than 60 percent of the nation’s schoolchildren, while blacks and Latinos are a little less than one-third together. Nevertheless, it’s important to look at group averages, not simply absolute numbers. If blacks have an exceptionally high poverty rate and few have incomes above the national average, that is obviously a cause for social concern. So too with disparities in educational performance.

Since the numbers we discuss in this chapter and later are deeply depressing, the reader should remember that they are not measurements of fixed, innate traits that are independent of the environment and cannot be changed. If we thought that, we would not have written this book. The measurements that are the foundation of this work register how well or badly groups of young people are developing the intellectual skills that are essential to doing well in America today and tomorrow. Only by recognizing the severity of the problem can we begin to think about possible remedies. The racial gap in academic achievement is a problem that can be solved; there is a way, if we have the will.

A small thought experiment perhaps illuminates the seriousness of the gap today, however. To function well in our postindustrial, information-based economy, students at the end of high school should be able to read complex material, write reasonably well, and demonstrate a mastery of precalculus math. Imagine that you are an employer considering two job applicants, one with a high school diploma, the other a dropout at the end of eighth grade. Unless the job requires only pure brawn, an employer will seldom find the choice between the two candidates difficult.

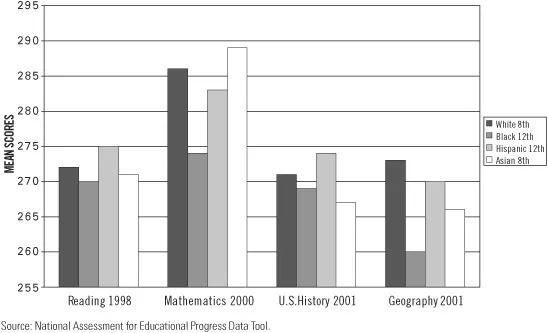

The employer hiring the typical black high school graduate (or the college that admits the average black student) is, in effect, choosing a youngster who has made it only through eighth grade. He or she will have a high school diploma, but not the skills that should come with it. This shocking fact is plain from Figure 1-1, which displays the results of the most recent NAEP tests in four core subjects.6 Figure 1-1 reveals that blacks nearing the end of their high school education perform a little worse than white eighth-graders in both reading and U.S. history, and a lot worse in math and geography. In math and geography, indeed, they know no more than whites in the seventh grade.7

Hispanics do only a little better than African Americans. In reading and U.S. history, their NAEP scores in their senior year of high school are a few points above those of whites in eighth grade. In math and geography, they are a few points lower.

Asians, by contrast, perform about the same as whites, despite the fact that they are a nonwhite racial group. They fall a bit below the white average in history and geography, but are a bit ahead in mathematics.

Figure 1-1. The Four-Year Gap: How Black and Hispanic High School Seniors Perform Compared to Whites and Asians in the 8th Grade

“Below Basic”

Looking at the average black or Hispanic student as compared to the average white or Asian student yields these depressing results. There is another way of judging the magnitude of the racial gap in academic achievement.8 The NAEP assessments report not only average scores for each racial or ethnic group; they also place each individual test-taker in one of four different “achievement levels.” The bottom is labeled Below Basic, which is reserved for students unable to display even “partial mastery of prerequisite knowledge and skills that are fundamental for proficient work” at their grade. Those who have only a partial mastery are at the Basic level. To rate as Proficient, the next step up, students must give a “solid academic performance,” demonstrating “competency over challenging subject matter.” Advanced, the highest achievement level, is reserved for a performance that is “superior.”9

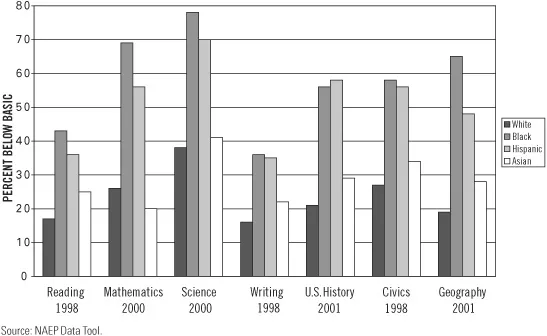

An alarmingly high proportion of all American students, the NAEP results show, are leaving high school today with academic skills that are Below Basic. In reading and writing, it is nearly one-quarter of all students. In geography, math, and civics, it is about a third. A dismaying 47 percent of all students ranked Below Basic in the 2000 science assessment. Worse yet, in American history the figure in 2001 was 57 percent.

Some experts have charged that NAEP has set its achievement levels unrealistically high.10 Possibly so. Certainly, the definition of “Basic” does not seem to be consistent across subjects, since less than a quarter of students at the end of high school are Below Basic in both reading and writing, while in American history and science the figure is roughly 50 percent. Is the typical student really that much weaker in history and science than in reading and writing? Maybe. But it is also possible that the experts who decided what students should know simply had higher expectations in some subjects than in others.

This controversy, however, has little bearing on the issue that concerns us. Whether the standards in particular subjects err in being too tough or too easy, within each subject they are applied in precisely the same way across the racial and ethnic spectrum. The question is how racial groups compare in their distribution at the four achievement levels. Figure 1-2 provides the answer.

It shows that the proportion of white students who have not acquired even Basic skills by twelfth grade is around one-fifth in most subjects, and it exceeds one-third only in science. Asian-American pupils did about the same as whites, though it is somewhat surprising that significantly more of them fell into the Below Basic level in science.

Figure 1-2. Percentage of 12th-Graders Scoring “Below Basic” on the Most Recent NAEP Assessments

The figures for whites and Asians are worrisome. But the rather disappointing scores of many whites and Asians look good when compared with those of blacks and Hispanics. Only in writing is the proportion of African Americans lacking the most basic skills less than 40 percent. In five of the seven subjects tested, a majority of black students perform Below Basic. In math, the figure is almost seven out of ten, in science more than three out of four. These are shocking numbers. A majority of black students do not have even a “partial” mastery of the “fundamental” knowledge and skills expected of students in the twelfth grade. In most subjects, but particularly in math and science, Hispanic students at the end of high school do somewhat better than their black classmates, but they, too, are far behind their white and Asian peers.

Employers who seek to hire young people who are literate and numerate will thus be hard pressed to find non-Asian minority applicants who qualify. Approximately two-thirds of black and Hispanic students do not enter the workplace immediately, but go on to college, and a great many are clearly entering higher education unprepared for true college-level work—work that assumes a basic mastery of high school material. That is a subject to which we will return in the next chapter.

High Achievers

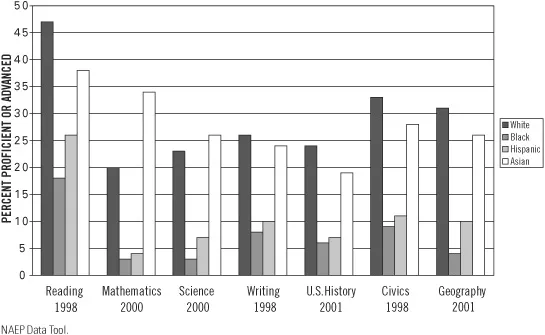

That so many black and Hispanic students have had at least twelve years of schooling without developing even the most fundamental skills is alarming. The news is no happier when we switch our gaze from those at the bottom to those who are at the top. In 1990, the National Education Goals Panel set a national objective that every student become proficient in basic subjects by the year 2000. We didn’t come close to meeting that objective by 2000, but the 2001 No Child Left Behind legislation reaffirmed that aim—universal “proficiency.” Thus, it is important to ask who is meeting that standard? Figure 1-3 gives the answers.

The criteria developed by NAEP’s experts, we see again, vary considerably from subject to subject. A much higher proportion of students are judged Proficient or Advanced in reading, for example, than in mathematics or science. But within each subject, the differences between whites and Asians, on the one hand, and blacks and Hispanics on the other hand, are huge.

Nearly half of all whites and close to 40 percent of Asians in the twelfth grade rank in the top two categories in reading, while less than a fifth of blacks and a quarter of Hispanics achieve that level. In science and math, a mere 3 percent of black students were able to display more than a “partial mastery” of the “knowledge and skills that are fundamental for proficient work” at the twelfth-grade level, in contrast to seven to ten times as many whites and Asians. Hispanics performed only a bit better than blacks in each of these subjects.

Figure 1-3. Percentage of 12th-Graders Rated as “Proficient” or “Advanced” on the Most Recent NAEP Assessments

The disparities are even greater if we look only at the elite within the elite—at the very small group of students whose performance is rated as Advanced. These are the academic stars whose records will catch the eye of admissions officers at Ivy League or comparably competitive schools. For all groups, the numbers are small. Only the top 3.4 percent of white students and 3.0 percent of Asian Americans score at the Advanced level in science. But for African Americans, the figure is just 0.1 percent. The black-white disparity is thus 34 to 1, and the Asian-black disparity 30 to 1. In math, only 0.2 percent of black students are Advanced; the figure for whites is 11 times higher and for Asians 37 times higher.11 Hispanic students are but a shade ahead of blacks in the proportion of high performers in every subject. Again, these are very sobering figures, suggesting a state of emergency. With so few blacks and Hispanics with superb academic skills by the end of high school, the pool of those destined to become part of the American professional and business elite is very small.

These glaring disparities shape educational policy in the K–12 years and beyond. They drive the widespread and controversial use of racial double standards in admissions to selective colleges and universities. If black and Hispanic applicants to highly competitive schools were judged by the same academic standards as whites and Asians, the number accepted in the immediate future would be very low—much lower than it is today. As it is, glaring racial double standards are needed in order to get a freshman class that is as much as 6 or 7 percent black at schools like Wesleyan and the University of Michigan. The demand for academically highly accomplished black and Hispanic students is much greater than the current supply.12

Narrowing or Widening?

Is the gap getting narrower or is it widening? That obviously matters. But the answer depends upon the baseline one starts from.

Blacks have made tremendous educational gains since the days of Jim Crow, when roughly 80 percent of African Americans grew up in the South, where they were legally required to attend segregated schools. Not only were these schools generally mediocre; most did not go beyond eight grades because white officials assumed th...