![]()

CHAPTER 1 Westward March

“Thare is good land on the Massura for a poar mans home.”

THIS THEME, PENNED IN AN 1838 LETTER from Arkansas to Tennessee, appears with its variations as the moving spirit of western migration. The frontiersman who scrawled out the good news from the banks of the White River probably had no conception of the wide reach of land between his few acres and the Pacific shore. He dreamed no dream of empire. His eye was on the good land he had found, where a “poar man” could prosper.

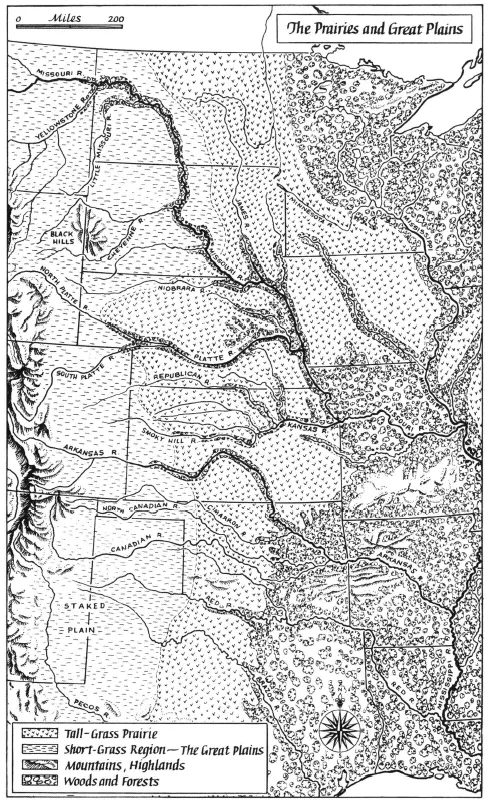

To settlers on the bottom lands of the great midwestern rivers and on the forested fringes of the Great Plains, the West of the 1830s was a rumor of indefinite obstacles. Known in its parts by a few trappers and explorers, it was grasped as a whole by no one. The sources of its great rivers, the extent of its mountain ranges were a matter of vague conjecture by geographers, who often depicted the continental features as they “must be” rather than as they were. These maps of the literate were only a little more useful than the rumors of the semiliterate.

The great desert and the “shining mountains” stood as a barrier to the settlers who had flowed across the Alleghenies. Even the approaches to the mountains were forbidding. Between the western edge of settlement and the Great Divide lay the treeless plains, where wind and alkali dust accompanied fierce storms, and tribes of Indians roamed in search of buffalo.

Beyond the horizon of the settlers were the trappers and traders, less concerned with rumors, correcting the maps while they read them. “The Rocky Mountains,” wrote trader Joshua Pilcher in 1830, “are deemed by many to be impassable, and to present the barrier which will arrest the westward march of the American population. The man must know little of the American people who supposes they can be stopped by any thing in the shape of mountains, deserts, seas, or rivers.”

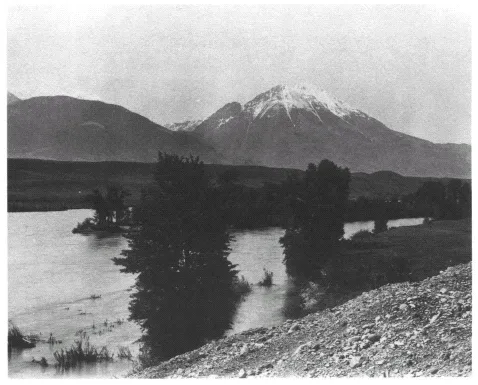

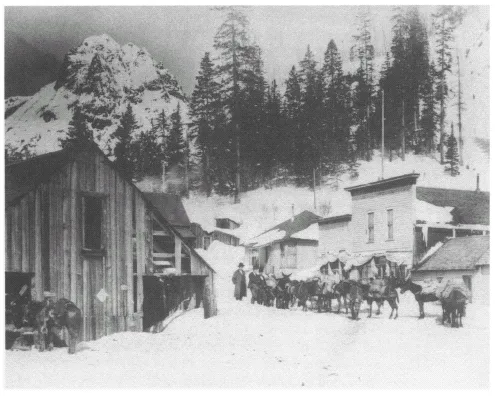

To the westward-pushing settlers, the land beyond the Missouri was barricaded by mountains that could not be crossed by wagons. Sometimes referred to as the “shining mountains,” they were eternally snow covered. (Photograph courtesy of F. J. Haynes Studios, Inc., Bozeman, Montana.)

That same year the company of Smith, Jackson and Sublette, fur traders, demonstrated that the plains, at least, could be crossed by wagons “in a state of nature.” In April 1830, a caravan of ten wagons and two dearborns left St. Louis and crossed to rendezvous in the Rocky Mountains. Twelve cattle and a milk cow were driven along “for support.” Grass was abundant, and buffalo beyond requirements, so that the expedition returned, rich in beaver pelts, with four oxen and the milk cow.

“The wagons,” wrote the partners, “could easily have crossed the Rocky Mountains over the Southern Pass.” Actually, they agreed, the route from the Pass to the great falls of the Columbia River was easier than the eastern slopes, except for a “scarcity of game.”

Two years later, the steamboat Yellowstone ascended the Missouri to Fort Pierre on behalf of the American Fur Company, and so demonstrated a second practical means of western travel. The desert was vulnerable by land or water. The way was open for the “poar man” with his family and household goods to find good land “on the Massura”—or beyond.

The settlers came. They were not stopped by anything. They came, first, for good land; and when gold was discovered the gold-hunters joined the ranks of the land-hungry. First a trickle, then a torrent, the migration westward became a phenomenon in American history unique in numbers and distances. For fifty years the westward migration continued, until the good land from the Missouri to the Pacific was peopled, and the frontier was declared to be past tense.

Crossing the plains and mountains, easy for the professional fur traders and explorers, offered greater obstacles to the land-seekers, amateurs in the business of travel in a tree-less, water-poor wilderness. The emigrants carried more than “twelve cattle and a milk cow.” Hunting buffalo was a new experience. The overlanders had not the contempt for difficulties bred by familiarity into the mountain men. Men and women loaded their children and their goods into wagons, and on horseback. Most found a canvas-covered wagon the best vehicle. Wide tires kept the wheels from sinking into the sand. During the travel season, May to September, lines of these prairie schooners stretched from the Missouri River to the Snake.

For settlers with no baggage or little money, the luxury of a prairie schooner was abandoned in favor of carts. Many people simply walked across the plains, pack on back. There were instances of persons starting the journey pushing wheelbarrows. To all of the emigrants the trip was a series of new, strange, and often terrifying incidents.

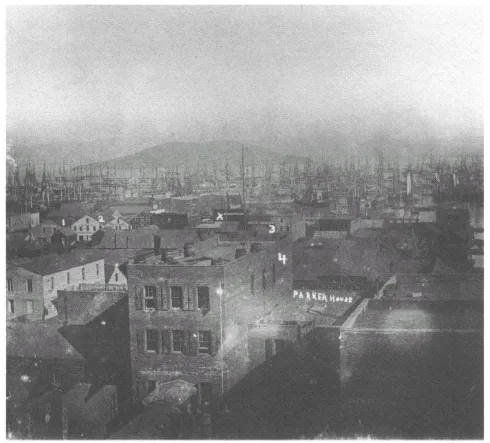

For western travelers with money, sailing or steaming around the Horn, or via the Isthmus to the Pacific coast, was a way of escaping alkali dust. During the California gold rush, passengers and crew alike abandoned ship in San Francisco harbor to seek their fortunes. Ships were anchored helplessly until repentant sailors, disappointed in the diggings, came back to work. Passage on ’Frisco-bound vessels was less hazardous than overland trips, but scurvy, storm, starvation, and lack of water took their toll. (Courtesy of the California State Library.)

Trail customs became standardized by experience and force of circumstance. Every well-run wagon train formed a corral of vehicles at the end of the day’s journey for protection against Indians, and to provide a fenced enclosure for livestock.

All Western rivers could be forded at some point. At an easy crossing, the stream was shallow, and the ox teams simply pulled the wagons through. At deeper crossings, oxen and cattle had to swim; the wagons were converted into crude boats. Accidents at fords were common, and many an emigrant ended his journey swept down the river.

Mountain trails were also an impediment to travel. Space between the water’s edge and canyon walls was sometimes barely enough for wagon wheels. When the cliffs pressed too closely, wagons waded to the other side, or used the streambed as a road. At one point on the Mullan Road (in Montana), regarded as an improved route, the St. Regis River had to be crossed nineteen times in six miles.

The average emigrant was not wealthy. By contemporary account. “His tone was dim, not to say subdued. His clothes butternut. His boots enormous piles of rusty leather, red from long travel, want and woe. From a corner of his mouth trickled ‘ambeer.’ His old woman, riding in the wagon, smoked a corn-cob pipe, and distributed fragments of conversation all around.” (So many of them seemed to come from the Pike country in Missouri that the place achieved lasting fame in an overland ballad.)

Many of the first pathbreakers wrote letters home, and prepared itineraries for neighbors and kin who were to follow. “Guides” were published for the aid and comfort of the emigrant. Advice in such literature was based on tragic experience.

“Build strong wagons, with three-inch tires held on by bolts instead of nails.”

“Obtain Illinois or Missouri oxen, as they are more adaptable to trail forage, and less likely to be objects of Indian desire.”

“Every male person should have at least one rifle gun.”

“Of all places in the world, traviling in the mountains is the most apt to breed contentions and quarrils. The only way to keep out of it is to say but little, and mind your own business exclusively.”

Much of the hardship associated with overland travel could be avoided by taking passage on a Missouri River steamboat to Fort Benton (northwest of Great Falls in Montana), head of navigation. While steamboat travel upstream was slower than a brisk walk, it was also more comfortable, and usually safer. Though most important as carriers of freight, steamboats brought many emigrants on the first leg of their trip to the new land.

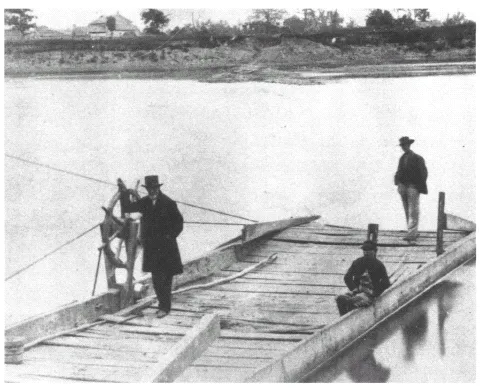

As the Western emigrant trails became established, enterprising persons rigged ferries across the larger streams along the route. Such ferries were usually the cable and scow type, motivated by the river current. Ferry proprietors were necessarily rough characters, as they had to defend their business from competitors and from persons offering shotgun toll. This ferry crossed the Kaw River. (Photograph by Alexander Gardner Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society.)

Whatever the size of outfit or means of travel, the emigrants shared certain experiences common to all who came to the West. Their experiences have become symbols of the trek: the ferries and fords, Chimney Rock, Devil’s Gate, the first buffalo, boiling springs, the Pass, alkali deserts. And Indians, who were also a hazard of the trail. “As long as I live,” warned Red Cloud of the Sioux, “I will fight you for the last hunting grounds of my people.” The United States Army garrisoned the plains routes, but the few soldiers could not protect every dangerous mile of the road. The sight of death on the trail was a universal experience—death by cholera, death in childbirth, “mountain fever,” or a violent death in battle. The graves, quickly dug and marked, were part of the price paid for the free land and the great opportunity at the end of the trail.

To the poor man or woman in search of a better home, the wilderness that was the Oregon Country was very inviting. Traversed by Lewis and Clark, stronghold of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and enthusiastically described by missionaries, the Willamette Valley drew settlers two thousand miles over desert, mountain, and plain.

The most well known of these trails was the Oregon Trail. Stretching from Independence, Missouri, to the Dulles, Columbia River, in Oregon, the trail became the main thoroughfare to the Pacific Northwest. After Lewis and Clark, the infamous John C. Frémont, with the help of the colorful guides Kit Carson and Thomas Fitzpatrick, was sent by the War Department in 1842 to do a more extensive survey, ensuring better and somewhat safer passage.

For those emigrants whose destination was the Pacific coast and who had more than average means, the sailing ship and steamboat offered a way of reaching the new land without the hardships of the overland route. Many voyagers found, to their sorrow, that they had exchanged one set of hazards for another.

Gradually the major Western routes became well defined, the worst gullies were smoothed over, the roads kept free from fallen trees, and the steepest grades eased. The Indian threat was subdued. Travel was less hazardous. Toll roads and ferries were established by enterprising persons who tarried on the route, grasping their opportunity on the spot. By the time of the Civil War it was possible to ride an overland stage from Missouri to San Francisco. The stage was comparatively fast, but, as one passenger declared, the ride was “twenty-four days of hell.”

Efforts to improve means of overland travel led to some odd innovations. During the 1860s, both Joseph Renshaw Brown of Minnesota and Thomas L. Fortune of Mount Pleasant, Kansas, conceived the idea of a steam-propelled wagon, a prairie motor, designed to haul freight over the plains. But both the Fortune wagon and Brown’s device proved impractical for freight work.

Not all western migration was pointed beyond the mountains. The “desert” of the Great Plains lost much of its terror, and attracted the land-hungry. To the settlers who came from timbered country, the plains were a “perfect ocean of glory.” Here one could strike a sodbuster and circle a section of land without more obstacles than a few buffalo chips. Water was scarce, but the land was good, and a person could always hope.

As the railroads advanced westward with the aid of the land-grant system, settlement of the plains progressed more rapidly, and with a new pattern. The railroad companies recognized the economic importance of population along the right-of-ways. As they laid track, the lines competed for settlers, and offered attractive inducements to prospective emigrants.

In 1885 the Union Pacific posted special rates of forty-five dollars from the Missouri River to Portland, Oregon, with a free baggage allowance of 150 pounds. Berths in emigrant sleeping cars were free. “The emigrants,” said a company leaflet, “are hauled in their own sleeping cars attached to the regular passenger trains.”

Agents working for, or in cooperation with, railroad lines sponsored colonies. To settle the vast prairie lands, the railroad immigration agents sought out entire congregations and villages. As Jay Cooke, financier of the Northern Pacific, phrased it. “The neighbors in the Fatherland may be neighbors in the new West.” To encourage colonists, the Northern Pacific built reception houses for the trainloads of new settlers, sold “ready-made” homes, offered terms of 10 percent down and the balance in ten annual payments. The company offered to donate a section of land to each colony for religious purposes.

To the railroad colonies came groups of Civil War veterans looking for a new start, entire congregations from England, and shiploads of emigrants from Europe. Max Bass, remarkable promotion agent of the Great Northern Railroad, gathered a colony of Dunkers from Indiana and settled them in North Dakota. The special train made up to transport the colony was routed through Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin by daylight, so the public could read the banners hung on the cars: “From Indiana to the Rich, Free Lands in North Dakota, the Bread Basket of America!” The train stopped in the Union Station at St. Paul, where Max Bass arranged to have a photograph taken. On March 3, 1894, the Dunkers arrived at Cando, and began a new life as wheat farmers.

Mountain travel was made easier when toll roads were established. Road builders constructed easier grades, kept the road free from fallen trees, and filled in the worst holes. Dollarhide’s Station (above) on the toll road across the Siskyou Mountains from California to Oregon was a major travel point. Through these gates passed stagecoaches, freight wagons, circus trains, pack mules, gold-hunters, itinerant preachers, and travelers whose business was best not asked. It was a lively spot to be (Photo by Peter Britt, courtesy of the University of Oklahoma.)

Many of the hopeful land-seekers were disappointed in the land, the climate, and in their neighbors, but the stubborn ones endured the first hardships, and stayed.

Whether on a wheat ranch, in the gold fields, or on an Oregon donation land claim, the first consideration of the pioneer was for a house. Shelter for the family, rather than architecture, was the primary concern.

The “axe and augur dwelling” was the most common arrangement in a land where timber was easily available. As the name implies, such a house was built of logs, held together by wooden pins and gravity. The result of a workmanlike job was a “snug home in the wilderness.” Inept or careless work produced a house “as tight as the end of a woodpile.” A mud, stone, and sod chimney and fireplace heated the cabin, and provided cooking facilities. The primitive bed, referred to as a “prairie rascal,” was ...