![]()

1. Monkey See, Monkey Do

What could be easier than matching the length of two lines?

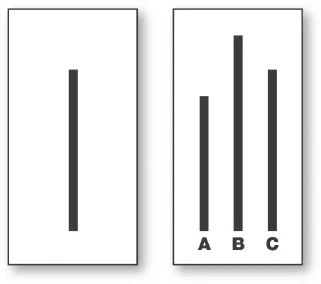

Imagine you were asked to participate in a basic vision test. In front of you is a pair of cards. On the left card is a line. And on the right card are three comparison lines, A, B, and C.

Your job is simple. Just pick the line on the right that is the same length as the target line on the left card. Decide whether line A, line B, or line C is the same length as the target line. Should be easy, right?

Now let’s add one more wrinkle. Rather than doing the experiment alone, you participate with a group of your peers.

You show up at a nondescript building on a university campus, and walk up a flight of stairs to room B7. You see that six other people are already seated around three sides of a square table, so you grab the last remaining chair, the second from the end.

The experimenter gives the instructions. He reiterates that your job is to pick the line on the right that is most similar in length to the one on the left. The group will do a number of trials just like the one above. As the group is small, and the number of trials relatively few, he’ll call on each person in turn to announce their choice, which he’ll record on a special form.

The experimenter points to the person on the left side of the table and asks him to start. This first participant has red hair, is wearing a grey collared shirt, and seems to be around twenty-five years old. He looks at the same lines you saw on the last page and, without missing a beat, reports his judgment: “Line B,” he says. The next participant seems a little older, maybe around twenty-seven, and is dressed more casually. But he reports the same answer. “B,” he says. The third person also says B, as does the fourth, and the fifth, and then it gets to you.

“What’s your answer?” asks the experimenter. Which line would you pick?

When psychologist Solomon Asch designed this line length study in 1951, he was testing more than people’s vision. He was hoping to prove someone wrong.

A few years earlier another psychologist, Muzafer Sherif, had conducted a similar study and found surprising results.1 Sherif was interested in how norms form—how groups of people come to agree on common ways of seeing the world.

To study this question, he put people in an unusual situation. In a dark room, Sherif displayed a small pinpoint of light on the wall. He asked people to stare at the light and not move their eyes for as long as possible. Then he asked them to report how far the point of light moved.

The point of light was immobile. It didn’t move at all.

But for individuals in the room, the light seemed to shift ever so slightly. Gazing at a small dot of light in an otherwise dark room is tougher than it sounds. After staring in the darkness for a while, our eyes fatigue and move involuntarily. This tendency causes the point of light to seem as though it moves even though it doesn’t.

Sherif studied this phenomenon, called the autokinetic effect, because he wanted to see how people might rely on others when they were uncertain.

First he put people in the room alone, by themselves. Each person picked a number based on how far they thought the light moved. Some people thought two inches, others thought six inches. Different people’s estimates varied widely.

Then, Sherif put those same people into groups.

Rather than making their guesses alone, two or three participants would be in the room at the same time, each making estimates that the others could hear.

People didn’t have to agree; they could guess whatever they wanted. But when placed together, what was once a discordant mix of differing views soon became a symphony of similarity. In the presence of their peers, the guesses converged. One participant might have said two inches when she was by herself, while another might have said six inches. But when placed together they soon came to a common estimate. The person who said two inches increased her estimate (to something like three and a half inches) and the person who said six inches decreased his estimate (to something like four inches).

People’s estimates conformed to those around them.

This conformity happened even though people were unaware it occurred. When Sherif asked participants whether they were influenced by the judgments of others, most people said no.

And social influence was so strong that it persisted even when people went back to making judgments by themselves. After the group trials, Sherif split people up and had them return to making guesses alone. But people continued to give the answers that they had settled on with the group, even after the group was gone. People who had increased their estimates when others were in the room (from two to four inches, for instance) tended to keep guessing that larger number even when they were by themselves.

The group’s influence stuck.

Sherif’s findings were controversial. Do people just do whatever others are doing? Are we mindless automatons who simply follow others’ every action? Notions of independence and free thought seemed at stake.

But Solomon Asch wasn’t convinced.

Asch thought conformity was simply a result of the situation Sherif used. Guessing how far a point of light moved wasn’t like asking people whether they like Coke or Pepsi or whether they want butter or cream cheese on their bagel. It was a judgment most people had never made, or even thought of making. Further, the right answer was far from obvious. It wasn’t an easy question. It was a hard one.

In sum, the situation was ripe with uncertainty. And when people feel uncertain, relying on others makes sense. Others’ opinions provide information. And particularly when people feel unsure, why not take that information into account? When we don’t know what to do, listening to others’ opinions, and shifting ours based on them, is a reasonable thing to do.

To test whether people conformed because the answer was uncertain, Asch devised a different experiment. Rather than putting people in a situation where the answer was unclear, he wanted to see what they would do when the answer was obvious. When people could easily tell the correct answer right away and thus would have no need to rely on others.

The line-length task was a perfect choice. Even those with poor eyesight could tell the correct answer. They might have to squint a little, but it was right there in front of them. There was no need to rely on anyone else.

Asch thought that when the answer was clear, conformity would be reduced. Drastically. To provide an even stronger test, Asch rigged the group’s responses.

There was always one real participant, but Asch filled the rest of the room with actors. Each actor gave predetermined responses. Sometimes they gave the right answer, picking the line on the right that was the same as the one on the left. But on other preselected trials, all of them gave the same wrong answer, saying “Line B,” for example, when the answer was clearly line C.

Asch used the line task because he assumed it would reduce conformity. Real participants could see the right answer, so it shouldn’t matter that others gave the wrong response. People should act independently and go with what they saw. Maybe a couple participants would waver once in a while, but for the most part people should give the right answer.

They didn’t.

Not even close.

Conformity was rampant. Around 75 percent of participants conformed to the group at least once. And while most people didn’t conform on every trial, on average, people conformed a third of the time.

Even though people’s own eyes told them the correct answer, they went along with the group. Even when they could clearly tell that the group was incorrect.

Solomon Asch was wrong and Sherif was right. Even when the answer is clear, people still imitate others.2

THE POWER OF CONFORMITY

Imagine a hot day. Really hot. So sweltering that the birds won’t even sing. You’re parched, so you drop into a local fast-food restaurant to grab a cold drink. You walk up to the counter and the clerk asks what you’d like.

What generic term would you use if you wanted a sweetened carbonated beverage? What would you say to the clerk? If you had to fill in the blank “I’d like a ____________, please,” how would you do it?

People’s answers depend a lot on where they grew up. New Yorkers, Philadelphians, or people from the northeastern United States would ask for a “soda.” But Minnesotans, Midwesterners, people who grew up in the Great Plains region of the country would probably ask for a “pop.” And people from Atlanta, New Orleans, and much of the South would ask for a “Coke.” Even if they wanted a Sprite.

(For fun, try ordering a Coke next time you’re in the South. The clerk will ask you what kind, and then you can tell them a Sprite, Dr Pepper, root beer, or even a regular Coke.)1

Where we grow up, and the norms and practices of people around us, shape everything from the language we use to the behaviors we engage in. Kids adopt their parents’ religious beliefs and college students adopt their roommates’ study habits. Whether making simple decisions, like which brand to buy, or more consequential ones, like which career path to pursue, we tend to do as others around us do.

The tendency to imitate is so fundamental that even animals do it.

Vervets are small, cute monkeys found mostly in South Africa. Similar in size to a small dog, they have light-grey bodies, black faces, and a fringe of white around their stomachs. The monkeys live in groups of ten to seventy individuals, with males striking out on their own and changing groups once they reach sexual maturity.

Scientists often study vervets because of their humanlike characteristics. The monkeys display hypertension, anxiety, and even social and abusive alcohol consumption. Like humans, most prefer drinking in the afternoon, rather than morning, but heavy drinkers will drink even in the morning and some will even drink until they pass out.

In one clever study, researchers conditioned wild vervets to avoid certain foods.3 Scientists gave the monkeys two trays of corn, one containing pink corn and the other blue corn. For one group of monkeys, the scientists soaked the pink corn in a bitter, repulsive liquid. For another group of monkeys, the researchers flipped the colors—blue tasted bad and pink normal.

Gradually, the monkeys learned to avoid whichever color tasted bad. The first group of monkeys avoided the pink corn while the other group avoided the blue. Just like soda in the Northeast and pop in the Midwest, local norms had been created.

But the scientists weren’t just trying to condition the monkeys, they were interested in social influence. What would happen to new, untrained monkeys who joined each group?

To see what would happen, the researchers took the colored corn away and waited a few months until new baby monkeys were born. Then, they placed trays of pink and blue corn in front of the monkeys. Except this time they removed the bad taste. Now the pink corn and the blue corn both tasted fine.

Which would the baby monkeys choose?

Pink and blue corn were just as tasty, so the baby monkeys should have gone after both. But they didn’t. Even though the infants weren’t around when one color of corn tasted bitter, they imitated the other members of their group. If their mothers avoided the blue corn, they did the same. Some babies even sat on the avoided color to eat the other, ignoring it as potential food.

Conformity was so strong that monkeys who switched groups also switched colors. Some older male monkeys happened to change groups during the study. Some moved from the Pink Avoiders to the Blue Avoiders, and vice versa. And as a result, these monkeys also changed their food preferences. Switchers adopted the local norm, eating whichever color was customary among their new group.

We might have grown up calling carbonated fizzy beverages “soda,” but move to a different region of the country and our language starts to shift. A couple years surrounded by people calling it “Coke” and we might find ourselves doing the same. Monkey see, monkey do.

WHY PEOPLE CONFORM

A few years ago, I flew to San Francisco for a consulting project. If you’ve been to the Bay Area, you know that on any given day the climate can be quite variable. Summers tend not to be that hot and winters don’t get terribly cold. But on any particular day, it’s hard to know what you’re going to get. San Francisco can easily be 70 degrees in November and 50 degrees in July. Indeed, a famous quote about the city—commonly (but erroneously) attributed to Mark Twain—is that “the coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.”

My trip happened to take place in November. Since I was traveling from the East Coast, I’d brought my heavy winter coat. But as I got ready to go out that first morning in San Francisco, I faced a dilemma: Should I wear my coat or not? I checked the weather report, which suggested the temperature would be somewhere in the high 50s to low 60s, but I still wasn’t sure. That sounded right on the margin between warm and cold. How to decide?

Rather than just guessing myself, I used a time-tested trick: I looked out the window to see what other people were wearing.

When we’re not sure about the right thing to do, we look to others to help us figure it out. Imagine looking for a parking spot. After driving around for what seems like forever, you find a whole side of a street free of cars. Success! But excitement quickly turns to concern: If no one else parked here, maybe I shouldn’t, either. There might be street cleaning or some special event that makes parking there illegal.

If there are even a couple other cars parked on the street, though, the concern disappears. You feel more confident you’ve found a legitimate spot.

Trying to sort out which dog food to buy or which preschool to send your child to? Knowing what others have done provides insight into what might be best for you. Talking to other dog owners who have similar breeds will help you figure out the right food option for your dog’s size and energy level. Talking to other parents will help you figure out which schools...