![]()

Just how much microscopic life dwells inside you?

If we’re going by weight, the average adult is carrying about three pounds of microbes. This makes your microbiome one of the largest organs in your body—roughly the weight of your brain and a little lighter than your liver.

We’ve already learned that, in terms of sheer numbers of cells, the microbial cells in our bodies outnumber the human cells by up to ten to one. What happens if we measure by DNA? In that case, each of us of us has about twenty thousand human genes. But we’re carrying some two million to twenty million microbial genes. Which means that, genetically speaking, we’re at least 99 percent microbe.

If you want a salve for human dignity, think of this as a matter of complexity. Every human cell contains many more genes than a microbial cell. But you contain so many microbes that all their various genes add up to more than your own.

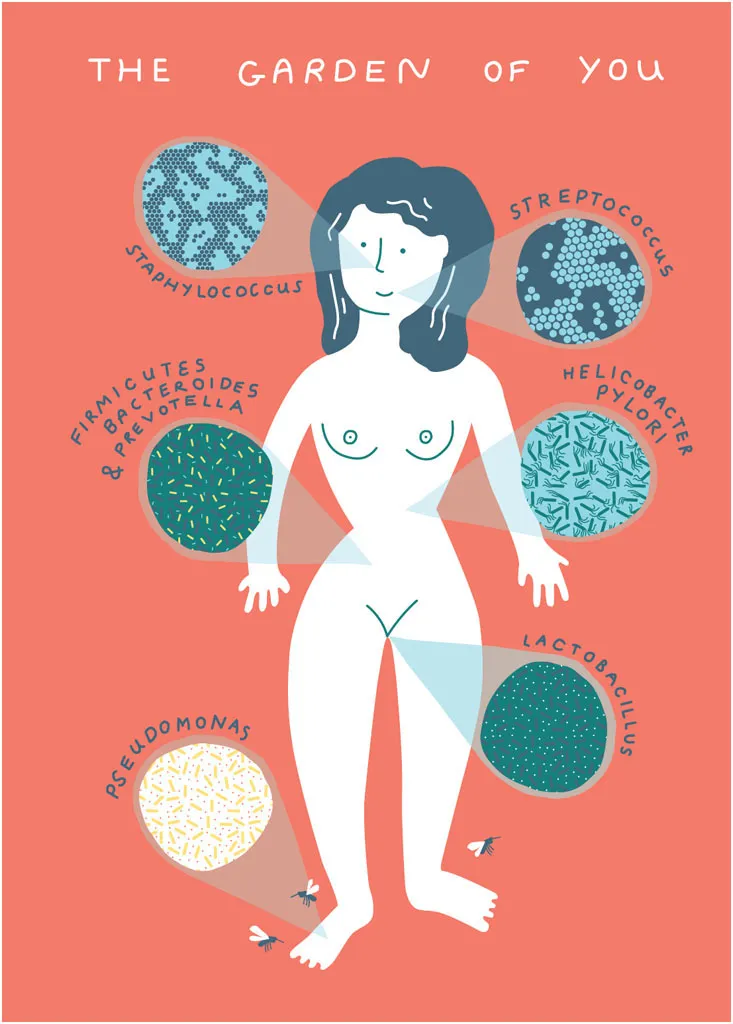

The organisms that live within and upon us are many and varied. Most, but not all of them, are single-celled organisms. They come from all three main branches of the tree of life. You might find in your gut members of the archaea, single-celled organisms that make do without nuclei; the most common of these are the methanogens, creatures that exist without oxygen, help digest our food, and excrete methane gas. (Cows have them, too.) Then there are eukaryotes, such as the fungi of athlete’s foot, and the yeasts that colonize the vagina and sometimes our gut. And most dominant of all, there are our bacteria, like Escherichia coli, which we think of mostly as an illness to be caught from underwashed spinach but that actually exists in harmless and helpful versions within most human intestines.

And every day, with the help of new technology, we discover that these creatures are still more diverse than we knew. It is almost as though we had been trawling the ocean with a very wide-meshed net and concluded that marine life consisted entirely of whales and giant squid. We’ve discovered that there’s so much more out there. For instance, you might guess that any two bacteria in your gut, feeding on your latest sandwich, are pretty similar—as similar as, say, an anchovy and a sardine. In fact, their differences are more like a sea cucumber and a great white shark: two creatures with radically different behaviors, nutrient sources, and ecological roles.

So where are all of our microbes, and what are they doing? Let’s take a tour of our bodies and find out.

Skin

Napoléon I, returning from a campaign, supposedly sent a message ahead to the empress Joséphine: “I will return to Paris tomorrow evening. Don’t wash.” He preferred his beloved’s scent, and a lot of it. But why is it that, when we are disarmed of our soaps, antiperspirants, powders, and perfumes, we stink so? Largely because of microbes that feast on our secretions and make them yet smellier.

Scientists are still sniffing out what productive purpose the creatures living on our largest organ, our skin, might serve, but this much is certain: they contribute to our body odor, including the scents that attract mosquitoes.1 As noted earlier, mosquitoes do prefer the smell of some individuals over others, and microbes are responsible. These microbes metabolize the chemicals our skin produces into different volatile organic compounds that the mosquitoes like or dislike. Different species of mosquitoes favor different parts of our bodies. For Anopheles gambiae, one of the main mosquitos that transmit malaria, the alluring odors aren’t coming from our armpits but from our hands and feet. This raises the intriguing possibility that antibiotics rubbed on the hands and feet might ward off attacks from this particular mosquito because by killing the microbes, you’d kill the smell.

Like all our microbes, those on our skin don’t necessarily exist for our benefit. But as benign inhabitants, they actually help us a great deal: simply by taking up residence upon us, they make it harder for other, nastier microbes to infect us. Different parts of the skin have different microbes on them, and the diversity—the number of different kinds of microbes—isn’t necessarily linked to the number of individual microbes you have in a particular location. Often it’s the reverse. In American terms, imagine if Vermont (population, six hundred thousand) had the ethnic diversity of Los Angeles County (population, ten million), and Los Angeles was as monochromatic as Vermont. Your armpits and your forehead have a lot of microbes but relatively few species; in contrast, the palm of the hand and the forearm are sparse microbial habitats, but many species accumulate there.2 Women tend to have more diverse microbial communities on their hands than men do, and these differences survive hand washing, suggesting that they may stem from biological differences, although the cause is still unknown.3

We’ve also found that the microbes living on your left hand are different from the microbes on your right. For all of the hand-wringing, knuckle popping, and touching of the same surfaces that our hands do, each develops distinct microbial communities. This inspired Noah Fierer, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, in Boulder, and me to try to reproduce one of the most famous findings in large-scale biology. British biologist and anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace and others developed an elaborate theory of biogeography to help explain the dispersal of organisms among islands, and the relationship between species diversity and land area.4 Wallace, Darwin’s contemporary and codiscoverer of natural selection, discovered a split running through present-day Indonesia and Malaysia that separates the Asian fauna (monkeys, rhinoceroses) from the Australian fauna (cockatoos, kangaroos). Fierer and I wanted to know if we could find the same “Wallace line” between the letters G and H on computer keyboards, with distinct populations from its users’ left and right hands colonizing each half of the device. We also wondered if the space bar had more kinds of microbes simply because it’s larger than the other keys.

Our results suggested a sort of Wallace line, but we were astonished to find something much more remarkable: each fingertip and its corresponding key had essentially the same microbial community. We could also match up someone’s computer mouse to the palm of his or her hand with more than 90 percent accuracy.5 The microbes on your hands are very distinct from other people’s—on average, at least 85 percent different in terms of species diversity—which means that you have a microbial fingerprint.

We have taken our research further, performing experiments to understand how many times you have to touch an object to leave these detectable microbial traces. The science is still too preliminary to stand up in a court of law. But TV crime dramas employ, shall we say, slightly lighter standards of evidence, so, shortly after we published the first paper on the topic, CSI: Miami aired an episode that used microbial forensics as its premise.6

Meanwhile, David Carter, a forensic microbiologist, recently moved from Nebraska to Hawaii, where he is setting up a body farm. A body farm, you ask? Forensic scientists have to figure out how long corpses they find have been dead. Inside a forensic facility, donated bodies are laid out in different death scenes7 and then examined every so often to see how they are decomposing. There’s a remarkable microbial succession. Just like bare rock is colonized first by lichens, and then, sequentially, mosses, grasses, weeds, shrubs, and, finally, trees, the process of decay follows a very predictable pattern.

Jessica Metcalf, a postdoctoral researcher in my lab at the University of Colorado Boulder, has built her own miniature body farm using forty dead mice. (The mice were killed as a by-product of other experiments aimed at discovering cures for heart disease and cancer.) She found she could estimate when the mice had died within a three-day window, which is about as accurate as current insect-based methods8 for dating corpses. Why use microbes, then? Insects have to find the corpse, whereas the microbes are right there with you all along, which could make them useful in insect-free crime scenes.

Nose and Lungs

Moving along on our tour, let’s look up your nose. The human nostril harbors its own distinct microbes. Among them is Staphylococcus aureus, the bacterium that causes staph infections in hospitals. Healthy people, it seems, are often home to what we consider dangerous microbes. What we think might be going on here is that the other bacteria you have in your nose may prevent S. aureus from gaining a foothold, or, rather, a nose hold. Another interesting finding is that our environments greatly influence the types of microbes that gather in our noses. And children who have more diverse kinds of bacteria in their nose early on, such as those who live on or near farms, are less likely to develop asthma and allergies later in life.9 It turns out that playing in the dirt can be good for you.

Down in your lungs, we usually find only dead bacteria.10 The lungs’ air-exposed surfaces contain a cocktail of antimicrobial peptides: tiny proteins that kill bacteria as soon as they land. In sick people, though, such as those with cystic fibrosis or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), you’ll sometimes find harmful microbes that contribute to pulmonary disease.11

Whether your throat has its own distinct microbiome, or just has microbes from the mouth passing through, is still a matter of scientific debate.12 However, we can say that the microbes in the throats of smokers appear to be different from those of nonsmokers, perhaps showing that smoking is harmful not just to us but also to some of the creatures that live within us.13

Mouth and Stomach

You’ve probably heard only about the bad bacteria in your mouth—the ones that can cause gum disease and tooth decay. One bad bug is called Streptococcus mutans, a creature that likes to eat our teeth. It seems to have evolved along with human agriculture,14 which made our diets much richer in carbohydrates, especially sugars. Just as we have inadvertently domesticated rats to eat food out of the garbage, bacterial vermin have been domesticated to live in our bodies. Fortunately, most of the domesticated bacteria in our mouths are beneficial, forming biofilms that keep out the bad bacteria. Our mouth microbes may even help regulate our blood pressure by relaxing our arteries with a compound they help produce called nitric oxide (a chemical relative of the nitrous oxide you’ve experienced in the dentist’s chair).

Another species, called Fusobacterium nucleatum, is normally found in healthy mouths but can also contribute to periodontal disease.15 F . nucleatum is interesting because it has been observed within the tumors of people with colon cancer.16 We don’t know yet whether this association is cause or effect: F. nucleatum might produce the disease, or it might simply be responding to the environment where the tumor lives. The microbes in your mouth are also quite diverse. Even different sides of the same tooth can harbor their own microbial communities, which could be influenced by many factors, including oxygen exposure and chewing patterns.

In the stomach, we find a highly acidic environment, like a car battery, where only a few kinds of microbes survive. But those microbes can be very important. One in particular, Helicobacter pylori (or H. pylori), has lived with us for so long that we can tell which human populations are closely related—and with whom they came in contact as they migrated—by looking at the particular strains of H. pylori they harbor.17

H. pylori play a key role in ulcers, those sores in the stomach or small intestine where the protective mucous lining has been worn away and gastric acid gnaws at the body’s tissue. Symptoms start with bad breath and burning stomach pain, and escalate to nausea and bleeding out of both ends. For years, doctors blamed ulcers on stress and diet, advising patients to relax and cut out spicy foods, alcohol, and coffee. Milk and antacids were recommended. Patients experienced some relief but rarely recovered fully.

Then in the 1980s, Australian physicians Barry Marshall and J. Robin Warren showed that most ulcers are actually caused by H. pylori infections and can be treated with antibiotics or chemicals such as bismuth, which target the bacteria. In fact, Marshall was so convinced of this that he drank a culture of H. pylori, gaining himself curable gastritis and a Nobel Prize, the latter of which he shared with Warren.

And yet today we are learning that something like half of the entire human population carries H. pylori. So why don’t they all have ulcers? It seems that H. pylori is only one of many risk factors for ulcers: necessary but not sufficient. H. pylori, along with a great many bacteria we associate with disease, turns out to be something that many people carry without complaint. One of the challenges and promises of microbiome science is figuring out how and why these microbes sometimes turn on us.

Intestines

Next, we come to the intestines. We believe this to be the largest and most important microbial community in the body. If you’re a microbe living on a human, this is the main act. Here is the great mansion of our gut, some twenty to thirty feet long and full of nooks and crannies. I...