![]()

Henry VI, Part 1

Henry VI, Part 1 is an uncompromising celebration of early English nationalism and imperialism. It defines the English against the French, whom it degrades as scheming, effeminate, and willing to consort with the devil. The play idealizes the English king Henry V for his successful conquest of much of France during the Hundred Years War. But Henry V has died just as the play begins, and leadership of the English cause in France has passed to Talbot, an indomitable, fierce, almost perpetually enraged, and therefore altogether masculine warrior hero. Yet Talbot is not as fortunate as Henry V. While all of France, we are told, shakes in terror at the name of Talbot, the French still refuse to yield.

Opposed to the idealized Talbot are a number of other characters who fail to match him. One is the official leader of the French, Charles the Dauphin, whose status as a military hero suffers a blow very early in the play when he must yield in single combat to Joan la Pucelle, or Joan of Arc. She then becomes the captain of the French, showing admirable cunning and resourcefulness in devising strategy and remarkable boldness in carrying it out. She fulfills for the French her claims to have been chosen by the Virgin Mary as the chaste instrument of France’s liberation from the hated English invaders. However, for the English, her shrewdness and power issue from the practice of filthy witchcraft, and her pretensions to chastity mask a characteristically French sensuality.

Also opposed to Talbot are many of the English, especially those who remain for the most part in England. They include Gloucester and Winchester, two bitter rivals more intent on defeating each other than the French. Gloucester, the Protector of the boy king Henry VI and therefore ruler of England, and Winchester, a bishop and cardinal, urge their servants on to brawl openly in the streets of London. Before their quarrel can be silenced, another breaks out between the Duke of Somerset and Richard Plantagenet, soon to be powerful as Duke of York. Once in France, they and their followers seek royal permission to fight each other, rather than the French. The play demonstrates, especially from this point on, that the French owe their victory to the English defeat of themselves. Talbot and his son, despite their glorious self-sacrifice in the English military cause (presented to inspire imitation among all Englishmen), cannot prevail against the French, because the rest of the English nobility are intent on preying on each other in the service of their own ambitions.

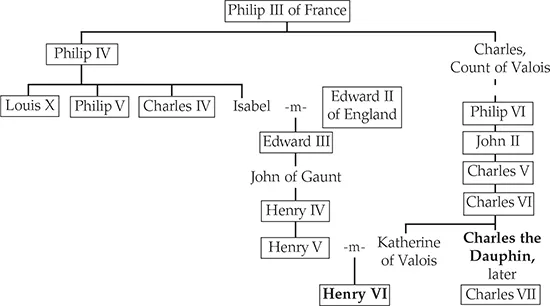

England’s Claim to France

[Characters in this play appear in bold]

After you have read the play, we invite you to turn to the essay printed after it, “Henry VI, Part 1: A Modern Perspective,” by Phyllis Rackin of the University of Pennsylvania.

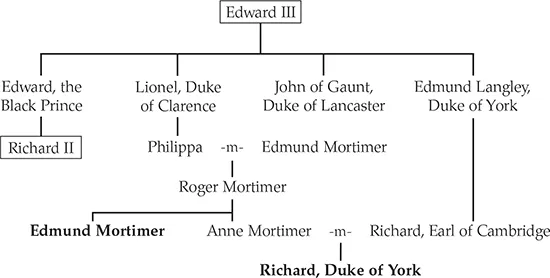

Ancestry of Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

[Characters in this play appear in bold]

![]()

Reading Shakespeare’s Language: Henry VI, Part 1

For many people today, reading Shakespeare’s language can be a problem—but it is a problem that can be solved.I Those who have studied Latin (or even French or German or Spanish) and those who are used to reading poetry will have little difficulty understanding the language of poetic drama. Others, however, need to develop the skills of untangling unusual sentence structures and of recognizing and understanding poetic compressions, omissions, and wordplay. And even those skilled in reading unusual sentence structures may have occasional trouble with Shakespeare’s words. More than four hundred years of “static”—caused by changes in language and in life—intervene between his speaking and our hearing. Most of his vocabulary is still in use, but a few of his words are no longer used, and many of his words now have meanings quite different from those they had in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the theater, most of these difficulties are solved for us by actors who study the language and articulate it for us so that the essential meaning is heard—or, when combined with stage action, is at least felt. When we are reading on our own, we must do what each actor does: go over the lines (often with a dictionary close at hand) until the puzzles are solved and the lines yield up their poetry and the characters speak in words and phrases that are, suddenly, rewarding and wonderfully memorable.

Shakespeare’s Words

As you begin to read the opening scenes of a play from Shakespeare’s time, you may notice occasional unfamiliar words. Some are unfamiliar simply because we no longer use them. In the early scenes of Henry VI, Part 1, for example, one finds the words vaward (i.e., vanguard), otherwhiles (i.e., occasionally, sometimes), intermissive (i.e., intermittent), and agazed (i.e., terrified). Words of this kind are explained in notes to the text and will become familiar the more early plays you read.

In Henry VI, Part 1, as in all of Shakespeare’s writing, more problematic are the words that are still in use but that now have different meanings. In the opening scenes of Henry VI, Part 1, for example, the word brandish is used where we would say “scatter,” car where we would say “chariot,” jars where we would say “quarrels,” and porridge where we would say “soup.” Such words will be explained in the notes to the text, but they too will become familiar as you continue to read Shakespeare’s language.

Some words and phrases are strange not because of the “static” introduced by changes in language over the past centuries but because these are expressions that Shakespeare is using to build a dramatic world that has its own space, time, and history. In the opening scenes of Henry VI, Part 1, for example, the dramatist quickly establishes a sense of an English government suffering such a loss in the death of its king that the cosmos seems to have turned against it: Henry V’s “thread of life” has been cut because of “revolting stars” and “planets of mishap,” and England is under the threat of becoming “a nourish of salt tears.” Such language quickly constructs the overwhelming sense of disaster surrounding the death of Henry V and the succession of his young son, Henry VI; the words and the world they create will become increasingly familiar as you get further into the play.

Shakespeare’s Sentences

In an English sentence, meaning is quite dependent on the place given each word. “The dog bit the boy” and “The boy bit the dog” mean very different things, even though the individual words are the same. Because English places such importance on the positions of words in sentences, on the way words are arranged, unusual arrangements can puzzle a reader. Shakespeare frequently shifts his sentences away from “normal” English arrangements—often to create the rhythm he seeks, sometimes to use a line’s poetic rhythm to emphasize a particular word, sometimes to give a character his or her own speech patterns or to allow the character to speak in a special way. When we attend a good performance of the play, the actors will have worked out the sentence structures and will articulate the sentences so that the meaning is clear. When reading the play, we need to do as the actor does: that is, when puzzled by a character’s speech, check to see if words are being presented in an unusual sequence.

Often Shakespeare rearranges subjects and verbs (i.e., instead of “He goes” we find “Goes he”). In Henry VI, Part 1, when the Messenger announces “Cropped are the flower-de-luces,” he is using such a construction (1.1.82). So is the Third Messenger when he says “Enclosèd were they with their enemies” (1.1.138). The “normal” order would be “the flower-de-luces are cropped” and “they were enclosed.” Shakespeare also frequently places the object before the subject and verb (i.e., instead of “I hit him,” we might find “Him I hit”). Winchester provides an example of this inversion when he says “The battles of the Lord of Hosts he fought” (1.1.31) and Gloucester another example when he says “Virtue he had” (1.1.9). The “normal” order would be “he fought battles” and “he had virtue.” With remarkable frequency, this play rearranges normal word order so that object precedes verb, which precedes subject: “Sad tidings bring I to you” (1.1.59); “No leisure had he to enrank his men” (1.1.117); “Nor men nor money hath he to make war” (1.2.17). Such word order is far more common in Henry VI, Part 1 than in plays whose Shakespearean authorship is not disputed.

Inversions are not the only unusual sentence structures in Shakespeare’s language. Often in his sentences words that would normally appear together are separated from each other, usually to create a particular rhythm or to stress a particular word, or else to draw attention to a needed piece of information. Take, for example, the Third Messenger’s “His soldiers, spying his undaunted spirit, / ‘À Talbot! À Talbot!’ cried out amain” (1.1.129–30). Here the subject (“His soldiers”) is separated from its verb (“cried”) by a participial phrase modifying the subject (“spying his undaunted spirit”) and by the object of the verb yet to come (“ ‘À Talbot! À Talbot!’ ”). As the Messenger’s purpose is to describe the devotion inspired by Talbot in the soldiers, the words that separate subject from verb have an importance that allows them to take precedence over the verb. Or take the Third Messenger’s introduction of Talbot’s plight on the battlefield:

this dreadful lord,

Retiring from the siege of Orleance,

Having full scarce six thousand in his troop,

By three and twenty thousand of the French

Was round encompassèd and set upon.

(1.1.112–16)

Here the subject and verb (“this dreadful lord . . . Was round encompassèd and set upon”) are separated by the two participial phrases “Retiring from the siege of Orleance” and “Having full scarce six thousand in his troop,” as well as by the adverbial phrase “By three and twenty thousand of the French.” By juxtaposing the slender troop strength of the English against the large body of the French, these interruptions emphasize that Talbot’s plight arises entirely from his being greatly outnumbered. In order to create sentences that seem more like the English of everyday speech, one can rearrange the words, putting together the word clusters (“Retiring from the siege of Orleance, having full scarce six thousand in his troop, this dreadful lord was round encompassed and set upon by three and twenty thousand of the French”). The result will usually be an increase in clarity but a loss of rhythm or a shift in emphasis.

Often in Henry VI, Part 1, rather than separating basic sentence elements, Shakespeare simply holds them back, delaying them until other material to which he wants to give greater emphasis has been presented. He puts this kind of construction in the mouth of the Third Messenger, who again is describing Talbot: “Here, there, and everywhere, enraged, he slew” (1.1.126). The basic sentence elements (“he slew”) are delayed until the Messenger presents the nearly superhuman ubiquity of Talbot and the quality of his disposition (“enraged”) that energizes his destructiveness. When Talbot himself speaks in 2.1, he is made to utter a sentence that also illustrates an even more extensive delay:

Lord Regent, and redoubted Burgundy,

By whose approach the regions of Artois,

Walloon, and Picardy are friends to us,

This happy night the Frenchmen are secure[.]

(9–12)

Talbot’s is a speech of welcome. Therefore it is appropriate for him to accentuate the importance of the newly arrived Burgundy by loading him with his titles (“Lord Regent, and redoubted Burgundy”) and celebrating his influence over “the regions of Artois, Walloon, and Picardy” before identifying by subject, verb, and predicate adjective the strategic advantage yielded the English and their allies by the dangerously overconfident French: “the Frenchmen are secure [i.e., overconfident, careless].”

Finally, in Shakespeare’s plays, sentences are sometimes complicated not because of unusual structures or interruptions but because the dramatist omits words that English sentences normally require. (In conversation, we, too, often omit words. We say, “Heard from him yet?” and our hearer supplies the missing “Have you.”) Shakespeare captures the same conversational tone in the play’s early exchange between Exeter and the Messenger. When Exeter asks how eight French towns and cities were lost, “How were they lost? What treachery was used?” the Messenger answers “No treachery, but want of men and money” (1.1.70–71). Had the Messenger answered in a full sentence, he might have said “No treachery [was used], but [they were lost through] want [i.e., lack] of men and money.” Ellipsis, or the omission of words not strictly necessary to the sense, appears a...