![]()

1

The Setting

THE LAND

About the size of Texas and nearly three times the size of the UK itself, Myanmar – also known by its colonial term ‘Burma’ – occupies approximately 261,552 square miles, the largest nation in Southeast Asia in terms of contiguous land mass. Longer than it is wide, the country’s major mountain chains – the Arakan, Pegu, Chin and Shan Yoma (meaning ‘main bone’, as in one’s spine, a common metaphor for mountain ranges) – lie north to south and slope east to west, while its major rivers – the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, Sittaung and Thanlwin (Salween) – run largely parallel to and in between them. The country is thus divided into long and wide plains areas, extremely conducive to north–south movement but more difficult when moving east–west, a configuration that has significantly shaped the country’s history and culture.

Among these large plains areas, the one belonging to the Irrawaddy River runs right down the country’s middle, and was (and still is) the most fertile and agriculturally productive region yielding the most variety of crops. It had (and still has) the greatest population density in the country, providing it with the wherewithal not only for the earliest but also the longest prehistoric and historic record, from which the country’s ‘classical’ civilization, its golden age, originates. It boasts the earliest, most sacred and largest number of the holiest shrines in the country, the most ‘orthodox’ of monasteries and the most learned of ecclesiastics in the country. It was (and is) also the country’s centre for producing the best of the fine arts and crafts, the most renowned masters of the theatrical arts and the most accomplished literary traditions and literature. And it was, for the greatest length of time, the most politically dominant region.

It is no surprise, then, that the names of places such as Pagan, Ava, Kyaukse, Minbu, Mandalay, Meiktila-Yamethin, Pyinmana, Pyi, Shwebo – all representing the country’s heart and soul, its ancient and earliest history, traditions and cultures, power and authority, in short, its civilization – recur time and again throughout the centuries until today. They evoke the same kinds of images and sentiments as when Kyoto and the Kyoto Plain of Japan, Delhi and the Yamuna-Ganges valley of India, Beijing and the Hwang Ho and Yangtze river valleys of China, Baghdad and the Tigris-Euphrates in Iraq, Mohenjo Daro and the Indus, and of course, Cairo and the great Nile are mentioned. In the same way the Irrawaddy River valley of Upper Myanmar is (and was) the ‘heartland’ of the country.

The general centre of this ‘heartland’ lies at the ‘Y’ created by the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers, extending south as far as Prome (Pyi) on the Irrawaddy, and to Toungoo, on the Sittaung. It is a large area that has come to be known as the Dry Zone, receiving on average only 45 inches of rain a year.

However, immediately north, west and east of it, especially in the hills, rainfall is abundant. These areas of much heavier rainfall are drained by hundreds of streams and rivers, most of which flow into the Dry Zone and into the major perennial rivers – the Chindwin, Irrawaddy and Sittaung – so that although the Dry Zone itself does not directly receive the kind of rainfall adequate for growing the most important annual cereal in the country – rice – it is nevertheless well watered.

In order to harness these rain-fed perennial streams and rivers flowing into the Dry Zone, sophisticated irrigation works were built and/or administered by the state (as well as non-state peoples) since ancient times. During the monsoons low-lying watersheds and flood plains in the middle of the Dry Zone inundate vast areas of land where catchment basins were dammed to store water during the dry season. The natural activity of the major rivers as well as the man-made canals and sluices for irrigation continuously enrich the central region with silt, turning the Dry Zone into a veritable oasis despite its appellation.

In fact, many parts of the Dry Zone such as the Mu, Kyaukse and Minbu valleys contain the most fertile land in the country, producing (for millennia) the largest variety of crops in addition to the staple: rice. That, along with more than the 150 days of sunshine needed to ripen this most important annual cereal ensured the regularity and predictability of a bountiful yearly harvest. Because there was a predictable food supply, which more often than not yielded a surplus, Upper Myanmar in general and the Dry Zone in particular throughout the history of the country attracted the most valuable asset in early Southeast Asia: people.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the earliest evidence of humans and human habitation can be found in these river valleys. Human settlements date back at least to the Palaeolithic Age (if not earlier), while the majority of the settlements belonging to the Neolithic and subsequent metal ages are also located mainly in sites nestled along, next (or with access) to, these rivers and their tributaries.

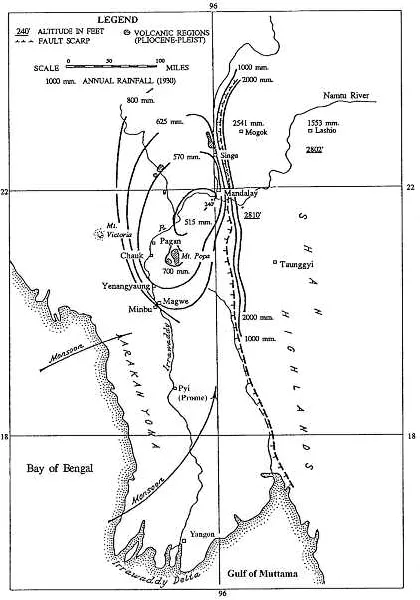

Climate and geological map.

Not surprisingly, the origins of the state lay in the Dry Zone of Upper Myanmar. Of the half dozen capitals of monarchical Myanmar, all except one were located here.1 The region retained that attraction for people throughout the country’s history until the very late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the British developed the Lower Myanmar Delta to become a new frontier and the new ‘rice bowl’ which finally began to draw people away from Upper Myanmar.2 Only then was there a shift in population density from Upper to Lower Myanmar, although the Irrawaddy River valley as a whole still contains the bulk of the population today. Population density was a sine qua non for state formation in labour-scarce Southeast Asia, so that whoever controlled the Irrawaddy River valley and its human and material resources, particularly of Upper Myanmar, nearly always also controlled the rest of the country.

All these factors led to a historical pattern in Myanmar history we have called ‘Dry Zone Paramountcy’ – the control of and/or hegemony over the whole country for most of its history from the Dry Zone. Only once, when Lower Myanmar’s Pegu in the mid-sixteenth century became the country’s capital did the centre of economic and political gravity shift to the south. Even then, it was temporary, lasting approximately 60 years before the capital moved back to the Dry Zone to remain there for another 300 years until the British conquered the country in the late-nineteenth century and re-established Lower Myanmar as the country’s seat by making Yangon (anglicized as Rangoon) their colonial capital. But as the capital of an independent political entity, Yangon (and Lower Myanmar) was to last even less than 60 years, for in 2005 a new capital (Naypyidaw) was built in the Dry Zone, adjacent to Pyinmana, an old governorship since the ‘classical’ period.3

Thus the conceptual and physical centre of the country has nearly always been associated with Upper not Lower Myanmar. Such ‘constancy of place’ preserved rather than changed that way of life. This phenomenon is seen by geographers as the ability of a particular geographic area to sustain a stable economic and political environment over a long period of time.4 It offered certain advantages, but produced analogous problems. Whereas it provides a predictable and dependable resource base (hence, a familiar and comfortable socio-psychological setting), it also tends to constrain the system from expanding beyond a certain limit, a kind of ‘braking mechanism’ that discourages society from leaving that comfortable situation for the unknown. It creates a conservative mind-set that resists fundamental (structural) change, one of the major themes in the history of Myanmar. Yet the role Upper Myanmar has played in the history, politics, economy, religion, society and overall mainstream culture of the country has been understated or minimized by present political concerns which attempt to trivialize that historical principle, ‘privileging’ instead the exceptions: the modern, the urban, the western, the coasts.

The geography of Myanmar had other kinds of effects on the country’s history. The rivers of these valleys provided an easy mode of transporting troops, peoples, goods and culture; they still do today. Exploiting the north to south flow of the current and the south to north movement of the wind made travel on the Irrawaddy River relatively fast both ways. A relay of war-boats that changed crews along riverine towns built precisely for that purpose could go from the Dry Zone (say Ava) to Dagon (modern day Yangon) in about five days. In pre-modern times in Southeast Asia, that was extremely fast. The trip up-river, of course, took longer, but even in 2004 an ordinary local sailboat going upstream, against the current but with the wind, moved faster than, and overtook the diesel powered tourist boat we were on in about half an hour.

On the west, east and north of these river valleys stands a wall of dense forests and relatively high mountains which contain rich natural resources. They include teak and numerous hardwoods as well as other forest products, along with valuable precious stones such as rubies and jade along with gold and silver. But these forests and mountains also act as physical barriers to invasion while encouraging economic self-sufficiency and relatively unfettered indigenous cultural development. In Myanmar, therefore, whereas mountain ranges have been dividers more than unifiers, rivers have been more unifiers than dividers.

Several hundred miles south of the Dry Zone is Lower Myanmar and the deltas of the Irrawaddy, Sittaung and Thanlyin (Salween). These are relatively recent geographic phenomena, attaining their present form only by or around the sixteenth century (and are still growing each day). And until the mid- to late nineteenth century, when the British drained, cleared and began cultivating the Irrawaddy Delta, it was largely mangrove swamps or otherwise unsuitable for cultivation. That was the reason the area was not well populated until the twentieth century when migration from the interior and immigration from British India and coastal China swelled the population density to levels we see today.

That natural geographic difference between Upper and Lower Myanmar was expressed conceptually in the Burmese terms anya (‘upstream’) and akye (literally, ‘the lower part of a river’, hence, ‘downstream’). ‘Downstream’ was usually a reference to the region south of Pyi (Prome) and Toungoo, the ‘gateways’ between Upper and Lower Myanmar. Pyi was the most important fortified city amongst Upper Myanmar’s kingdoms on the Irrawaddy and, situated at the southern end of the Dry Zone, it was also the staging area to points west, such as Rakhaing state (anglicized as Arakan) with its coasts on the Bay of Bengal. Toungoo, on the Sittaung River valley, assumed the same role on the east, with access points to the Shan states. The terms anya and akye had a cultural meaning beyond their geographic distinction: each depicted a particular way of life, attitude and behaviour without being considered foreign, much like the terms ‘Midwest’ or ‘East Coast’ do in the United States.

Although Lower Myanmar receives an inordinate amount of rain compared to the Dry Zone, because it is largely low lying, newly formed (or still forming) delta, its production of annual cereals was very minimal until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Only after the first quarter of the twentieth century did the Irrawaddy Delta unequivocally become the ‘rice bowl’ of British Burma. Even today large portions of the Irrawaddy and Sittaung deltas are still in the process of forming, much barely above sea level, and thus a difficult place to settle; while those areas that have been cleared and drained are suited mainly for monocrop production: rice.

As a result of all these factors Lower Myanmar has been less important politically in the country’s approximately 2,200-year pre-colonial history. The first distinct kingdom (or state, polity) there emerged only by the late thirteenth century, and had little or no impact on the country’s history and culture until more than two centuries later. Its historical development was also secondary, not primary, while its culture was derivative, not original. Indeed, Lower Myanmar as a region held sway over the entire country in pre-colonial times only once, and when it did, its dynasty came from the Dry Zone.

Buttressing coastal Myanmar are two major bodies of water that linked it to international and regional trade: the Gulf of Muttama (Martaban) and the Bay of Bengal. These were the major highways for external stimuli and influences: trade and commerce, culture and ideas. Lower Myanmar was thus a window to the maritime world and its international trade and cultural contacts, and also home to a mixture of different peoples and cultures, domestic and foreign. This was where the culture of the marketplace took root, with direct links to the outside world and its ideas, products and ways of life.

As a result people and society in Lower Myanmar were demographically and perhaps culturally more cosmopolitan, outward looking, changeable and flexible, and less homogeneous ethno-linguistically. They were more adaptable to sudden changes elsewhere in the external world, as their livelihood depended on that ability to change. Yet the causes for that strength were also the reasons for its weakness, for such a commercial society was vulnerable to outside events, disallowing long-term economic and political stability.

In contrast, Upper Myanmar’s agriculture was based largely on internally controllable factors – the maintenance of irrigation systems on perennial rivers, the administration of cultivator classes, the ability to clear and cultivate virgin land. As a result food production was also more regular and predictable than the uncontrollable international market situation of Lower Myanmar, thereby encouraging retention of the population, making Upper Myanmar society much more stable demographically, therefore, politically and socially as well.

It also had a conceptual and quantitative advantage: civilization there emerged centuries earlier (hence, its claim to the country’s origins and ultimate legitimacy), its population comprised the majority (hence, its superiority in numbers), and it controlled the country’s food supplies (hence, maintained its political power for most of the country’s history). Indeed, it was the interaction between these two varied ways of life that provided the country much of its dynamism, a topic to be discussed in chapter Four.

For too long the role of geography in the shaping of modern Myanmar, particularly of the inland agrarian interior, has been minimized and underestimated by historians while reified ethnicity, spectacular political events (often mere ‘incidents of the moment’) and trade and commerce have been ‘privileged’. We hope to change that perspective in this book.

NATURAL RESOURCES

In much the same way that pre-colonial society built its civilization on the geographic foundations given it, modern Myanmar has built upon the well-endowed natural resources that, until today, have remained largely untapped. It is still one of the least densely populated countries in Asia with 69.9 persons per square kilometre and an annual population growth of only 0.78 per cent. It produces more than enough food internally to feed its relatively low population of 59 million individuals. Approximately 41 per cent of its total habitat is still covered by woodlands and forests (with the second lowest rate of deforestation in Southeast Asia) and most of its natural resources are still intact. There is a plentiful supply of fresh water that far exceeds that available for India or China per capita, not to mention Africa.

The country is also known for its gems (primarily its rubies, considered the finest in the world, along with sapphires and jade), oil and natural gas (with 50 million barrels of proven oil reserves and 10 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves), and minerals such as tin, tungsten, lead, silver, copper and zinc. Its teak and other hardwoods remain some of the largest unexploited resources in the world.

The higher reaches of the country are covered with laterite (red soil leached of silica but containing iron oxides and hydroxide of aluminum) and the lower regions, especially the river valleys, with alluvial soil, mainly silt and clay. In the central Dry Zone the alluvial soil is black, rich in calcium and magnesium, but when the clay content is low it becomes saline under higher evaporation rates and turns yellow or brown.

It has a long coastline that provides ample marine products. Myanmar’s coastal waters are full of fish and shrimp, which still yield a bountiful harvest. Several points on the coasts of Myanmar, which comprise nearly 40 per cent of its boundaries, are natural harbours on the main trade routes to and from Asia. Although a few of these located at the mouths of rivers, such...