![]()

CHAPTER 1

Occupation and the Road to Two

Different German States

‘Germany First’: The European Advisory Commission

(EAC) of 1943–5

The attempts by Hitler to gain ‘Lebensraum’ (living space) for the German people through war against Poland in 1939 to create a Greater German Reich and the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 had failed due to the common efforts of the Allies. Up until 1943 there was neither agreement nor coordination between the three main Allies of the coalition against Hitler as to the question of what should happen after the victory. With the defeat of Nazi Germany in sight, the post-war planning of the Allies became more clearly engaged from the autumn and winter of 1943. The Moscow Foreign Ministers conference from 19 October to 1 November decided on the formation of the European Advisory Commission (EAC). From 15 December 1943 up to the conclusion of its activity on 2 August 1945 – its roles were then taken over by the Allied Control Council as well as by the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Four Powers – the EAC drafted four central pieces of documentation: first, the draft of a declaration of surrender (25 July 1944); second, an agreement by the Three Powers on the zones of occupation and the administration of ‘Greater Berlin’ (12 September 1944); third, the control mechanism (14 November 1944); and fourth, the declaration of the Four Powers in relation to the defeat and the assumption of the power of governing Germany (5 June 1945). Apart from Germany, the EAC was only concerned with Bulgaria and Austria. It was the British who were thinking most along European lines in the context of the EAC and who also were the most interested in its continued existence. The Allied Consultation Committee (ACC), which only had its first session on 18 December 1944, dealt with summaries of the proposals put forward by the ‘minor allies’ but these were hardly taken into account by the EAC. The British government kept their dominions informed in confidence about the consultations and gave privileged treatment to the French committee of liberation (CFLN). The other European exiled governments in London were generally only kept informed superficially and given short notice before the publication of the results. The treatment of the other partners as ‘minor allies’ demonstrated that for the USA and the USSR Europe was only a marginal factor. Although the work of the EAC made only slow progress, its output was considerable. In the shape of the agreements on the control procedures and the establishment of the occupation zones in Germany and Austria (including Berlin and Vienna) it had done decisive preliminary work for the future Four Power presence in the two countries. There was not a consensus for a dismemberment of Germany arising from the various deliberations of the ‘Big Three’. The EAC therefore aimed at only minimum compromises while a lot was left open as regards the fundamental questions over which the Allied Control Council in Berlin also failed. The great expectations that the British Foreign Office had had for the EAC were not to be fulfilled, particularly since it never discussed the shape of Europe in the post-war period. Quite apart from the fact that the EAC was sufficiently preoccupied with the agreements on the surrender and the occupation systems of Germany, the other members lacked the political will. Washington and Moscow were not prepared to make the EAC into a forum for the planning and restructuring of Europe after the end of the Second World War.

The Contradictory Liberation of 1945: Unconditional Surrender,

‘Collapse’ and ‘Zero Hour’

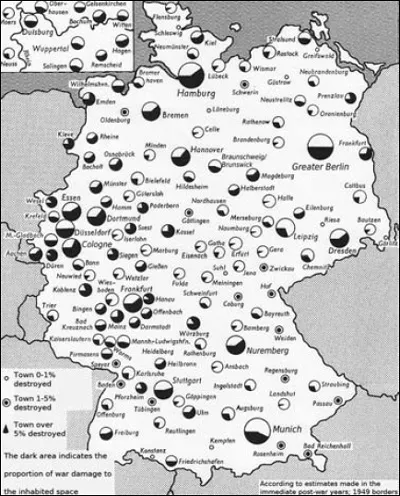

Following the demand of the coalition against Hitler at the Casablanca conference of 14–26 January 1943, the German Wehrmacht surrendered unconditionally on 8/9 May 1945. It is significant that two surrender documents were signed: in Reims for the Western military and Berlin-Karlshorst for the Soviet military. The end of the Nazi regime proceeded with the military occupation of the Reich by Allied troops. The victors and those suppressed and persecuted by the Nazis in the concentration camps saw the overcoming of Hitler’s Reich as a liberation from Nazi terror and referred to it as such. The majority of Germans did not necessarily see it as a liberation. In the wake of the complete collapse of the nation, the prevailing atmosphere was one of depression, but also one of relief at the end of a war that the Germans had experienced as a catastrophe due to the British, American and Canadian carpet bombing of the cities, a time of extreme privation and great suffering. Over 500,000 civilians had been killed. Many German towns were reduced to rubble and ashes in the last weeks of the war. Nearly 90 per cent of the beautiful medieval town of Hildesheim, with its many churches, was destroyed by British and Canadian bombs on 22 March 1945. This kind of liberation was ambivalent and contradictory, particularly since it was associated with the loss of family members as well as belongings and property. Not just large towns but even medium-sized and small towns were badly affected by bombing. Around five million homes were totally or considerably destroyed. The Germans lived in basements under the ruins, in Nissen huts or emergency dwellings. The supply of electricity and gas had largely broken down. Water was in short supply. The word Zusammenbruch (‘Collapse’) can be explained not only in relation to the collapse of the German Reich and the defeat of the Nazi regime. Buildings, institutions, traffic and transport infrastructure had collapsed and been destroyed; the railway and the postal service no longer functioned; the authorities and official services had disintegrated. The ‘liberators’ had not been summoned by the majority of the Volksgenossen (citizens of the Nazi state), nor had they desired the occupation. There were bans on fraternization. In 1945 one could still not speak of friendship and partnership in an alliance on a general level. For many people this year was a deep personal turning point: National Socialism had proved to be a criminal and destructive movement. Occasionally, one had shared the responsibility and the guilt. Traditions were severed and values shaken. Values like leadership, hard work, the nation, law and order had originally provided direction. Now they seemed worthless; in any case, they had been used as tools and corrupted by Hitler and his regime. For many Germans the occupation of the country meant insecurity and fear of the future. There were a number of suicides on the part of authority figures and civil servants along with those who supported and sympathized with National Socialism.

War damage in German towns.

The military occupation and the different occupation policy in the Soviet occupation zone and in the Western zones meant in practice the setting-up of different social, economic and organizational systems that brought about an internal split within Germany. It was not Hitler and his war that many Germans saw as a kind of punishment from God, but the different occupation practices and the diverging Allied ideas about a future resolution of the German question that led to the division of Germany.

For many refugees and people forced out of the former German territories in the East who ended up in what was to become the Federal Republic, the term ‘liberation’ came over as cynical. The people in the Soviet Occupation Zone did not feel at all liberated. Rapes, arrests and deportations were commonplace in the first months after the end of the war. A new dictatorship was set up, associated with repression and terror. At first, for many Germans, it was a matter of getting by from day to day. Together with the military authorities, transport problems had to be solved and the population supplied with food, fuel and clothing. The Trümmerfrauen (‘women of the ruins’) carried out valuable work clearing the rubble left over from the bombing and rebuilding the towns. The catastrophic situation as regards supplies was worsened by the refugees and people forced out of the former German territories in the East. The need for a political new start was seen as a zero hour, and referred to as such. In fact there were many ideological and personal continuities as regards the economy, politics and administration. The room for manoeuvre was limited by the fact that Germany was becoming the theatre of the East–West conflict in Europe that was taking on a global dimension. The occupation powers were the key factors in the political development, yet it would be wrong to think that the Germans were not able to take their fate into their own hands and join in the process of decision-making, as we shall see. At first, however, the Allies had all the say.

Yalta, Potsdam and the Forced Removal of Germans from

the Eastern Territories in 1945

At the conference in Yalta from 4 to 11 February 1945 the ‘Big Three’ – Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill – decided to divide Germany into zones. For Berlin, the capital of the Reich, there was to be a settlement as to the sectors. France was later recognized as an occupying power and was allocated its own zone in the southwest, made up from the American and the British zones, along with a sector in northwest Berlin. The British zone consisted of the northwest of Germany and the Americans had Bavaria along with Bremen and Bremerhaven. The USSR in its occupation zone in central and eastern Germany had put the north of East Prussia under its administration and the rest of Eastern Germany beyond the Oder-Neisse Line under Polish administration, without consulting the Western Allies. Germans living there were extradited and forced to flee. Stalin thus created a fait accompli and the Western powers looked on helplessly and without any power to act. The situation in the West was worsened by millions of refugees and people driven out of the former German territories in the East.

At the Potsdam conference of 17 July to 2 August 1945 far-reaching decisions about the future treatment of Germany were made. The aims of the Big Three were the abolition of the Nazi Party and its associations; decentralization of the German economy; removal of Nazis from official and semi-official positions as well as from positions of responsibility in private businesses; democratic renewal of education and the legal system; the reinstatement of local autonomy and permission for the formation of democratic parties. ‘German militarism’ and Nazism were to be ‘eradicated’ and all measures undertaken to prevent Germany from threatening her neighbours or the peace ever again. Part of this goal was the destruction and dissolution of ‘Prussia’, which was held to be the actual root of ‘German militarism’, and by a decision of the Allied Control Council in 1947 it was abolished. This decision was largely Winston Churchill’s; against this background he had agreed to the western shift of Poland carried out by Stalin in 1945 that had been allotted by him to the Soviet sphere of influence in the last years of the war.

The German population was to be given the opportunity to ‘reconstruct their life on a democratic and peaceful basis’. Clearly diverging concepts of ‘democracy’ still remained. The decision made in Potsdam to treat Germany as an economic unity was rejected and sabotaged by France, the fourth occupying power. The French rejection of a centralized administration covering all of Germany was to prejudice things in the direction of the division that took place in the following years. Furthermore, Potsdam established that the occupiers could demand reparations in their zones following their own imagination. Thus, the principle of economic unity was already damaged below the waterline. Germany’s foreign assets were taken over by the Allied Control Council and divided between the navy and the merchant marine.

A pie chart ‘Census of 13.9.1950’ shows the proportion of refugees and people forced to leave the former German Eastern territories. 56.9 per cent were from the Eastern territories, 24 per cent from Czechoslovakia and 8.2 per cent from the former republic of Poland and the Free City of Danzig (Gdansk), from Eastern and South Eastern Europe 8 per cent and from Western countries or from overseas 2.9 per cent.

In Potsdam, the Western powers were represented by new politicians who were partly inexperienced regarding foreign policy. The place of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who died on 12 April 1945 and who had been responsible for bringing the USA into the war, was taken over by Harry S. Truman. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill had been voted out of office and replaced by the Labour leader, Clement Attlee. Stalin exploited the weakness and indecisiveness of his Western negotiating partners. The Communist-led Polish government was to be given the Eastern German territories up to the Oder-Neisse Line in compensation for the Eastern Polish territories handed over to the USSR. This question led to conflicts in Potsdam, but in the agreement of 2 August 1945 the Western powers finally accepted the Oder-Neisse Line as the Western border of Poland, subject to a definitive resolution by the peace treaty with Germany. At the same time they agreed to the ‘transfer’ of Germans from these territories as well as from Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, which should be carried out ‘in an orderly and humane manner’. The reality looked completely different, however: forced removal had started months before the conference. The first waves of fleeing Germans got underway against the threatening background of the advancing Red Army. Further waves, which one could call an organized forced removal but which were officially termed ‘emigration’, were carried out in a disorderly and inhumane manner. Most of the people had to leave all their belongings behind. Approximately 12 to 14 million Germans were forced to flee from the former German Eastern territories and the neighbouring states (Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary). The number of dead and missing cannot be calculated exactly due to the chaotic circumstances. They are usually estimated at more than two million. Enormous numbers of people sought refuge in the ‘Free West’. The reception and integration of these masses of refugees into a land largely destroyed by the victorious powers, in which the indigenous population, themselves bombed out of their homes, found it difficult to gain shelter and in which the situation as regards supplies was extremely poor, presented an enormous additional challenge for the occupying powers and the German authorities. The overall integration of those forced to flee from the former German Eastern territories within what was to become the Federal Republic counts as one of the most considerable successes of post-war German society.

Allied Control of the Reorganization of Party

and ‘Länder’ Politics, 1945–7

The Allied Control Council met in the building of the former Berlin Supreme Court and consisted of the commanders-in-chief of the four victorious powers who, as military governors, formed the supreme governing body in each of their occupation zones. The Control Council was concerned with the abolition of Nazi laws and regulations and with denazification, demilitarization and dismantling in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement. It had no executive power, however, but had to rely on its decisions in the form of orders, directives, laws and proclamations being carried out by the respective military governors in the different zones. The Allied occupation was seen as an obstacle on the part of nationalistically and patriotically minded Germans in their attempts to overcome the division. The Allied Control Council did not agree on a common procedure for the creation of economic unity, as the Four Power agreement provided for. The individual commanders-in-chief of the Allied military forces were able to act on their own authority in their zones. As the supreme body the Allied Control Council had to make decisions on the basis of unanimity, i.e. it was unable to act in the event of a single veto.

The four military commanders-in-chief of the American, British, French and Soviet forces in Germany announced in their Berlin declaration of 5 July 1945 the setting up of the Allied Control Council, proclaimed on 30 August 1945. The USSR, USA, UK and France as the victorious powers had the supreme authority in Germany, divided into four occupation zones. Berlin was given four sectors and Four Power status. The occupying powers formed Länder based on the old territorial borders within their zones. Prussia, however, was divided up into several parts by the borders of the occupation zones. The administration was filled with Germans. As early as July 1945 the Länder of Sachsen (Saxony), Sachsen-Anhalt (Saxony-Anhalt), Thüringen (Thuringia), Brandenburg and Mecklenburg were established in the Soviet occupation zone. The Office of the Military Government of the United States (OMGUS) made Bavaria, Hessen (Hesse) and Württemberg-Baden Länder in September 1945 and Bremen in January 1947. From the middle of 1946 Nordrhein-Westfalen (North Rhine-Westphalia), Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony), Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg were formed in the British zone, Baden, Württemberg-Hohenzollern and Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate) in the French zone. The Saarland was given a special status and included within the French customs zone. Despite the occupation political life immediately sprang up amongst the Germans. The Allies tried to appoint politically untainted people as mayors and representatives of the Länder. In Summer 1945 political parties were permitted, often as regards their membership and organizational structure harking back to the Weimar Republic. On 10 June 1945 Moscow issued the order for the foundation of ‘democratic parties’ in the Soviet occupation zone. Germany as a whole was at no time involved to any extent. One day later the Central Committee of the German Communist Party (KPD) sent out a call also directed at the middle class. It was the first party to call in Berlin on 11 July 1945 for Germany to be shown ‘the way to the setting up of an anti-Fascist, democratic regime, a parliamentary democratic republic with all the democratic rights and freedoms for the people’. A union with the German Social Democratic Party (Sozial demo krat ische Partei Deutschlands, SPD) was still rejected. Walter Ulbricht, who shortly before the end of the war had flown from Moscow to Berlin as the leader of the exiled German Communists, was one of the signatories who launched himself with great commitment into the new political activity. Ulbricht was born the son of a tailor in Leipzig in 1893. In the course of his wanderings as an apprentice carpenter to Dresden, Nuremberg, Venice, Amsterdam and Brussels, in 1912 he joined the SPD. During the First World War he saw action in Poland, Serbia and on the Western Front. In 1918 as a member of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council of the XIXth army corps, after returning to Leipzig, he joined the Spartakist League. In 1919 Ulbricht became a member of the newly formed KPD and as early as 1923 a member of the Central Committee. For a short time in 1925 he worked on the Executive Committee of the Communist International at the Lenin School in M...