![]()

A Real Estate History of the Avant-Garde

A Few Evictions

Mission Bay will be the biggest development ever in San Francisco. The linchpin of this 300-acre site will be a huge new biotechnology facility built by the University of California, San Francisco. In its 8.1 million square feet of workspace, Mission Bay will create 42,000 new jobs, mostly high-paying, but only 6,000 units of housing, few of them affordable.1 This Catellus Corporation project will immediately displace the “vehicularly housed” community there, in what was long an abandoned railyard; it will make inroads on the scruffy houseboat community on Mission Creek—and some of those high-paid biotechnologists will start buying out Potrero Hill homes from under the residents, just as multimedia people are doing in the Mission. The worst-case scenario is historian Gray Brechin’s: Mission Bay is a toxic landfill site that in an earthquake will liquefy, spilling biogoop everywhere. Brechin remarks, “The main business of San Francisco is increasing the value of land, and Willie Brown understands that.”2 Twenty years ago, when he was in state government, Brown was the attorney for Mission Bay; as San Francisco’s mayor he’s completing a job he started on the other side of the fence. “We’re now, frankly, at the end of the rainbow,” he declared when he pushed the plan through the Board of Supervisors.3 Catellus Corporation is a spin-off of Southern Pacific, the “Octopus” of Frank Norris’s novel, a vast and vastly corrupt corporation that virtually ran California in its late nineteenth-century heyday. Of that day, Oscar Lewis wrote, “Although the citizens had on their side every important newspaper of the state save those frankly in the pay of the Southern Pacific, efforts to remedy the situation were uniformly unsuccessful because of the railroad’s control of the legislature, of state regulatory bodies, of city and county governments, and, in many cases, of the courts.”4 Mission Bay was its San Francisco railyard, and Catellus has inherited the SP’s position as the biggest nongovernmental landholder in the city—and the state.

But there’s more to San Francisco. The day I’m brooding on Mission Bay I go to hear scientist and environmental activist Vandana Shiva give a talk on what she calls “biopiracy,” the attempt by biotech companies to create genetically altered crops and then ensure markets for them by disrupting the peasant economy and sustainable agriculture in her homeland, India. Hilarious and scary, her exposition weaves together peasant uprisings, the dangers of monoculture, scientific madness (with examples such as cabbages into which scorpion genes have been spliced) and corporate greed. Brenda O’Sullivan from Modern Times Bookstore, one of the Mission’s longtime progressive institutions, is at the talk to provide the audience with copies of Shiva’s books, and the prolific and brilliant muralist Juana Alicia is in the audience, too. Mission Bay and Southern Pacific represent the central institutions of what Brechin calls “Imperial San Francisco,” but Juana, Brenda and the University of San Francisco faculty who invited Shiva represent the alternative institutions and traditions that are still a force in the city. Juana and her frequent collaborator, Miranda Bergman, present Shiva with the drawing for an addition to their huge mural covering the Women’s Building on Eighteenth Street near Valencia in the Mission. The addition portrays the four primary cereal grains eaten around the world and addresses genetic engineering and biodiversity. And, they tell Shiva, they’re going to add her name to the list of feminist heroines painted on the building. “This part of the building used to be an Irish bar, but we have enough Irish bars and not enough childcare here, so it’s a daycare center,” says Juana. Shiva is delighted and says that she believes it’s important that these issues become part of the culture.

Juana lures Miranda and me out to a Chinese restaurant in the Richmond District, where we continue our conversation. I tell her about Mission Bay and its probable effect on Potrero Hill’s housing. “There goes my dream of coming back,” she says. “I’ve painted this town, but I don’t think I can live in it again. And Emmanuel says, ‘Do you really want to live there? Everyone’s gone.’” Juana tells me that she and her husband, the artist Emmanuel Montoya, were evicted from the Mission in the early 1990s, which is how she came to settle in a flat on a busy street in the Western Addition, only a few blocks from the Coltrane church, Rexroth’s old digs, and the rest of that laden neighborhood that is still my neighborhood. But five years ago, in search of housing they could afford to buy, they moved to Berkeley (where they could not afford to buy now, she adds, as the inflationary ripple spreads outward). This is what makes the cultural raiding going on in the Mission matter. The Mission is home to the most significant concentration of murals in the country, and the murals represent an idea of art as part of everyday life, as a reinforcement of ethnic and sometimes feminist identity, a celebration of radical history, a populist art of the streets for those who use them. The murals mean that in moving through the streets, past churches and schools, Mission dwellers are moving through stories, past heroes, into legends and dreams.

The artists who came together in the early 1970s to make neighborhood culture organized against urban renewal when two stations of BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit, the intercity commuter train system) were put in on Mission Street as part of a plan to redevelop the neighborhood for downtown workers. Gentrification is, thirty years later, carrying out that redevelopment, with the delicate balance between the poor and the not-so-poor, the white and the nonwhite tipped by the multimedia invasion. One famous mural was painted over by the Cort Family developers, but it is not the extraction of the murals from the community but the community from the murals that poses the most serious threat. What Vandana Shiva said about the necessity of biodiversity could be equally applied to social diversity; it is what makes the city a thriving ecosystem, a garden in which the weeds sometimes bloom most brilliantly. Right now multimedia looks like monoculture. The expensive new businesses coming to the Mission include a plethora of restaurants and houseware and clothing stores, but bookstores, theaters, dance studios, galleries, “monoplex” movie houses and nonprofit activist organizations are shrinking, not multiplying, with this stage of gentrification.

Of course, progressive culture has its own history of displacements. As Juana obliquely mentioned, the Women’s Building evicted the Dovre Club, the Irish bar set into one corner of the Women’s Building like a chick under a mother hen’s wing. This had been my vision of the Peaceable Kingdom: a wholesome, mural-covered matriarchy featuring a four-story-tall Rigoberta Menchú that could still accommodate old-fashioned masculine versions of liberation—for the Dovre Club, which opened in 1966, was filled with Irish nationalist iconography and had been host to many radicals before the main space became a Women’s Building. A friend told me that when he used to participate in Starhawk’s pagan Spiral Dances in the Women’s Building’s gymnasium, he would occasionally duck out to watch a little football and have a shot of whiskey, and the world seemed to be in perfect harmony and balance. As several surviving bars testify, the Mission had, like the Castro, been a working-class Irish neighborhood, and when the Women’s Building evicted the Dovre Club, the new order at least symbolically squeezed out the old. Not that it was a black and white story, for the Dovre successfully relocated, and some of its defenders were among San Francisco’s most thuggish politicos. But the saga of the Dovre’s displacement is a reminder that the progressive version of San Francisco also squeezes out people and institutions. Americans tend to mistake powerlessness for innocence, because both are without impact; it is because the Women’s Building acquired power that it became able to evict. And Juana and Miranda will paint in panels about biodiversity where the Dovre once stood and a much-needed daycare center will open.

A Literary Eviction

Bohemia begins with an eviction. Or at least, Scènes de la vie de bohème, the book that introduced the word and the idea into popular consciousness does. “‘If I understand the purport of this document,’ said Schaunard re-reading an order to leave from the sheriff fixed to the wall, ‘today at noon exactly I must have emptied these rooms and have put into the hands of Monsieur Bernard, my proprietor, a sum of seventy-five francs for three quarters rent, which he demands from me in very bad handwriting.’”5 Henri Murger’s stories about a quartet of starving Left Bank artists were published serially beginning in 1845, turned into a wildly successful play in 1849, and gathered together in 1851 as a bestselling book (Puccini’s 1896 opera La Bohème, is, of course, based on Murger’s work). Murger’s stories about bohemia succeed in making poverty and its accompanying hunger, insecurity and occasional homelessness charming. The musician-writer Schaunard is a feckless garret-dweller who forgets about his eviction in a burst of inspiration. “And Schaunard, half naked, sat down at his piano. Having awakened the sleeping instrument by a tempestuous barrage of chords—he commenced, all the while carrying on a monologue, to pick out the melody which he had been searching for so long.”6 On goes the romp; he sets out to borrow the seventy-five francs, finds instead some drinking companions, the philosopher Gustave and the poet Rodolphe, drunkenly invites them back to the home that is no longer his and meets Marcel, the painter who has just moved in. More like the Three Musketeers than Les Misérables, the episode continues with the quartet forming the Bohemian Club and Schaunard becoming Marcel’s roommate. Community has triumphed over capital. Scènes is an episodic book, each chapter a picaresque adventure about love, friendship and scraping by. Murger concludes this first tale with the assertion that these “heroes belong to a class misjudged up to now, whose greatest fault is disorder; and yet they can give as an excuse for this same disorder—it is a necessity which life demands from them.”7

The Black Cat restaurant, Montgomery Street, early 1900s.

The city is both the place where society is administered and where it is transformed and challenged: it is both the Catellus Corporation operating a real-estate empire and the university bringing in Vandana Shiva to urge a responsive audience to resist corporate power. This mix that cities have traditionally provided makes them volatile, disorderly, creative and necessary, and the mixing is brought about in various ways. In San Francisco nowadays, home-builders are obliged to set aside a certain number of units as low-cost housing; in nineteenth-century Paris, low-cost housing was built into nearly every building. Before elevators, the top floor of Parisian buildings was designed as a sort of residential hotel—the rooms were called chambres de bonne, maids’ rooms, in my day, when poor students and African immigrants filled them; they usually had a cold-water sink and a communal toilet in the hallway (one cooked on a camping stove; refrigeration was the windowsill in winter). This building style created a sort of integrated housing: a famous illustration of the nineteenth century shows a cross-section of an apartment house with the bourgeoisie in armchairs just above the ground-floor concierge and the inhabitants getting progressively poorer as it ascended to the wretches huddled under the rooftop. Bohemia was the brownian motion of urban life; it brought together people of different classes, was the incubator for those who would rise through talent or sink through addiction, poverty, madness; was where the new would be tried out long before it would be found palatable in the mainstream; was where memory was kept alive as paintings, stories, politics.

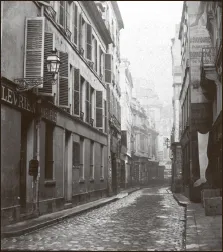

A Paris street c. 1865. Photograph by Charles Marville, courtesy Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco.

George Sand’s novel Horace gives a less prettified picture of bohemia at the time of the 1830 revolution; among the novel’s characters are dedicated painters and dilettantes, a slumming law-student squandering his provincial family’s funds and a dedicated peasant-revolutionary with great sculptural talent, as well as a few sympathetically drawn grisettes. Grisettes were working-class women who formed liaisons of various durations with the varying classes of men who formed bohemia (because the grisettes were seldom participants in creative life, save as muses and singers, and because they were unable to move out of bohemia into the salons, receptions and public arenas of the wealthy, bohemia’s freedom was largely male freedom—though Sand herself as a novelist and a lover broke its rules to free herself). The excitement of Paris or of any great city is that of feeling one is in the center of things, a place where history is made, where things count. Paris still has this sense to perhaps a greater extent than any other city (though Beijing, Prague, Manila, Los Angeles and Seattle have all had their moments).

Part of the fluidity of Parisian life comes from the way art has political weight, politics aesthetic merit, and figures such as Victor Hugo or Jean-Paul Sartre manage to act in both realms (something San Francisco has achieved in a very different way). Murger himself, the son of a conservative tailor, had gone to school with Eugène Pottier, who would write the Internationale. He remained apolitical while many of his circle—Baudelaire, Nadar, Courbet—became far more involved in the revolution of 1848. “Bohemia is the preface to the Hospital, the Academy, or the Morgue,”8 Murger wrote after he had become a success. The consequences of his success seem strangely familiar now: the Café Momus he had made famous became a tourist trap that the artists vacated. Murger himself moved to a Right Bank apartment and then became a country gentleman in the forest of Fontainbleau. His partner opened an antique furniture store back in Paris. This general pattern of bohemia prevailed through the 1950s, at least. Bohemia moved around; at the turn of the twentieth century, it was in Montmartre more than the Left Bank; for a long time it was various versions of Greenwich Village; and it appeared in San Francisco, too, at various times and addresses.

Cities had a kind of porousness—like an old apartment impossible to seal against mice, cities were impossible to seal against artists, activists, dissidents and the poor. The remodeling of Paris between 1855 and 1870 by Baron von Haussmann under the command of Napoleon III is well-known for what it did to people’s feelings, the poor and the old faubourgs. As Shelley Rice puts it in Parisian Views, “One of his first priorities had been to cut through and destroy the unhealthy, unsightly, and economically underprivileged areas that had been growing wildly and, in their horrific overpopulation, overtaking the heart of the town. By so doing the prefect hoped to roust the poor (who posed, he felt, a threat to both the city’s health and the stability of its government) to the outlying banlieus.”9 Haussmannization encompassed urban renewal, but it did more; it sought to reinvent the relation of every citizen to the city. In modernizing the city, Haussmann and his emperor did some inarguably good things: they provided pure water and sewage systems. They did, with the building of boulevards, some debatable things: the boulevards increased circulation for citizens, commerce and, occasionally, sold...