![]()

PART ONE

UNCOVERING A

HIDDEN DYNAMIC

IN THE CHALLENGE

OF CHANGE

![]()

[ 1 ]

RECONCEIVING THE

CHALLENGE OF CHANGE

WHAT WILL DISTINGUISH your leadership from others’ in the years ahead? As the subtitle of this book suggests, we believe it will be your ability to develop yourself, your people, and your teams. Throughout the world—and this is as true in the United States and Europe as it is in China and India—human capability will be the critical variable in the new century. But leaders who seek to win a war for talent by conceiving of capability as a fixed resource to be found “out there” put themselves and their organizations at a serious disadvantage.

In contrast, leaders who ask themselves, “What can I do to make my setting the most fertile ground in the world for the growth of talent?” put themselves in the best position to succeed. These leaders understand that for each of us to deliver on our biggest aspirations—to take advantage of new opportunities or meet new challenges—we must grow into our future possibilities. These leaders know what makes that more possible—and what prevents it.

The challenge to change and improve is often misunderstood as a need to better “deal with” or “cope with” the greater complexity of the world. Coping and dealing involve adding new skills or widening our repertoire of responses. We are the same person we were before we learned to cope; we have simply added some new resources. We have learned, but we have not necessarily developed. Coping and dealing are valuable skills, but they are actually insufficient for meeting today’s change challenges.

In reality, the experience of complexity is not just a story about the world. It is also a story about people. It is a story about the fit between the demands of the world and the capacity of the person or the organization. When we experience the world as “too complex” we are not just experiencing the complexity of the world. We are experiencing a mismatch between the world’s complexity and our own at this moment. There are only two logical ways to mend this mismatch—reduce the world’s complexity or increase our own. The first isn’t going to happen. The second has long seemed an impossibility in adulthood.

We (the authors of this book) have spent a generation now studying the growth of mental complexity in adulthood. We think what we have learned may help you to better understand yourself and those who work with you and for you. In gaining that awareness, you will begin to see a new frontier of human capabilities, the place where tomorrow’s most successful leaders will focus their leadership attention.

AN UPDATED VIEW OF AGE AND MENTAL COMPLEXITY

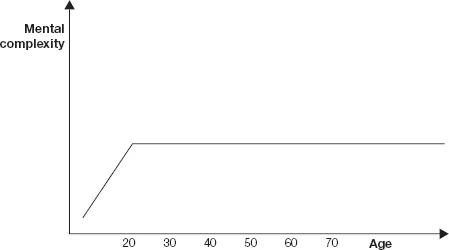

The ideas and practices you will find in this book begin by identifying a widespread misconception about the potential trajectory of mental development across the lifespan. When we began our work, the accepted picture of mental development was akin to the picture of physical development—your growth was thought fundamentally to end by your twenties. If, thirty years ago, you were to place “age” on one axis and “mental complexity” on another, and you asked the experts in the field to draw the graph as they understood it, they would have produced something similar to figure 1-1: an upward sloping line until the twenties and a flat line thereafter. And they would have drawn it with confidence.

When we began reporting the results of our research in the 1980s, suggesting that some (though not all) adults seemed to undergo qualitative advances in their mental complexity akin to earlier, well-documented quantum leaps from early childhood to later childhood and from later childhood to adolescence, our brain-researcher colleagues sitting next to us on distinguished panels would smile with polite disdain.

FIGURE 1-1

Age and mental complexity: The view thirty years ago

“You might think you can infer this from your longitudinal interviews,” they would say, “but hard science doesn’t have to make inferences. We’re looking at the real thing. The brain simply doesn’t undergo any significant change in capacity after late adolescence. Sorry.” Of course, these “hard scientists” would grant that older people are often wiser or more capable than younger people, but this they attributed to the benefits of experience, a consequence of learning how to get more out of the same mental equipment rather than any qualitative advances or upgrades to the equipment itself.

Thirty years later? Whoops! It turns out everybody was making inferences, even the brain scientists who thought they were looking at “the thing itself.” The hard scientists have better instruments today, and the brain doesn’t look to them the way it did thirty years ago. Today they talk about neural plasticity and the phenomenal capacities of the brain to keep adapting throughout life.

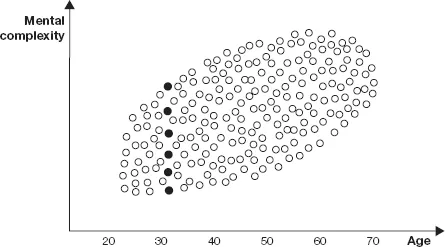

If we were to draw the graph showing age and mental complexity today? On the basis of thirty years of longitudinal research by our colleagues and us—as a result of thoroughly analyzing the transcripts of hundreds of people, interviewed and reinterviewed at several-year intervals—the graph would look like figure 1-2.

FIGURE 1-2

Age and mental complexity: The revised view today

Two things are evident from this graph:

• With a large enough sample size you can detect a mildly upward-sloping curve. That is, looking at a population as a whole, mental complexity tends to increase with age, throughout adulthood, at least until old age; so the story of mental complexity is certainly not a story that ends in our twenties.

• There is considerable variation within any age. For example, six people in their thirties (the bolded dots) could all be at different places in their level of mental complexity, and some could be more complex than a person in her forties.

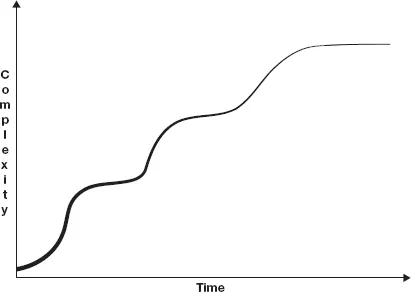

If we were to draw a quick picture of what we have learned about the individual trajectory of mental development in adulthood, it might look something like figure 1-3. This picture suggests several different elements:

• There are qualitatively different, discernibly distinct levels (the “plateaus”); that is, the demarcations between levels of mental complexity are not arbitrary. Each level represents a quite different way of knowing the world.

FIGURE 1-3

The trajectory of mental development in adulthood

• Development does not unfold continuously; there are periods of stability and periods of change. When a new plateau is reached we tend to stay on that level for a considerable period of time (although elaborations and extensions within each system can certainly occur).

• The intervals between transformations to new levels—“time on a plateau”—get longer and longer.

• The line gets thinner, representing fewer and fewer people at the higher plateaus.

But what do these different levels of mental complexity in adulthood actually look like? Can we say something about what a more complex level can see or do that a less complex level cannot? Indeed, we can now say a great deal about these levels. Mental complexity and its evolution is not about how smart you are in the ordinary sense of the word. It is not about how high your IQ is. It is not about developing more and more abstract, abstruse apprehensions of the world, as if “most complex” means finally being able to understand a physicist’s blackboard filled with complex equations.

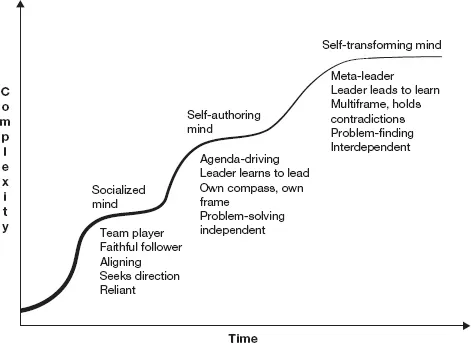

THREE PLATEAUS IN ADULT MENTAL COMPLEXITY

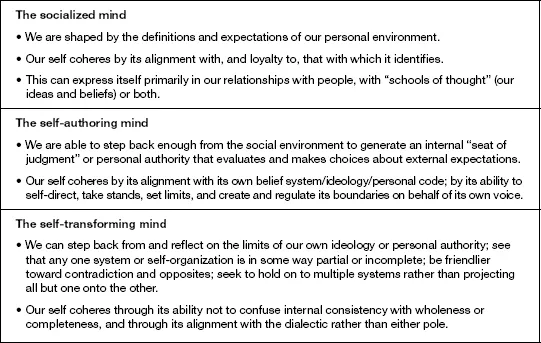

Later on in this book we will say more about these levels, but for now, let’s begin with a quick overview of three qualitatively different plateaus in mental complexity we see among adults, as suggested in figures 1-4 and 1–5.

These three adult meaning systems—the socialized mind, self-authoring mind, and self-transforming mind—make sense of the world, and operate within it, in profoundly different ways. We can see how this shows up at work by focusing on any significant aspect of organizational life and seeing how the very same phenomenon—for example, information flow—is completely different through the lens of each perspective.

FIGURE 1-4

Three plateaus in adult mental development

FIGURE 1–5

The three adult plateaus described

The way information does or does not flow through an organization—what people “send,” to whom they send it, how they receive or attend to what flows to them—is an obviously crucial feature of how any system works. Experts on organizational culture, organizational behavior, or organizational change often address this subject with a sophisticated sense of how systems impact individual behavior, but with an astonishingly naive sense of how powerful a factor is the level of mental complexity with which the individual views that organizational culture or change initiative.

Socialized Mind

Having a socialized mind dramatically influences both the sending and receiving aspects of information flow at work. If this is the level of mental complexity with which I view the world, then what I think to send will be strongly influenced by what I believe others want to hear. You may be familiar with the classic group-think studies, which show team members withholding crucial information from collective decision processes because (it is later learned in follow-up research) “although I knew the plan had almost no chance of succeeding, I saw that the leader wanted our support.”

Some of these groupthink studies were originally done in Asian cultures where withholding team members talked about “saving face” of leaders and not subjecting them to shame, even at the price of setting the company on a losing path. The studies were often presented as if they were uncovering a particularly cultural phenomenon. Similarly, Stanley Milgram’s famous obedience-to-authority research was originally undertaken to fathom the mentality of “the good German,” and what about the German culture could enable otherwise decent, nonsadistic people to carry out orders to exterminate millions of Jews and Poles. 1 But Milgram, in practice runs of his data-gathering method, was surprised to find “good Germans” all over Main Street, U.S.A., and although we think of sensitivity to shame as a particular feature of Asian culture, the research of Irving Janis and Paul t’Hart has made clear that group-think is as robust a phenomenon in Texas and Toronto as it is in Tokyo and Taiwan. 2 It is a phenomenon that owes its origin not to culture, but to complexity of mind.

The socialized mind also strongly influences how information is received and attended to. When maintaining alignment with important others and valued “surrounds” is crucial to the coherence of one’s very being, the socialized mind is highly sensitive to, and influenced by, what it picks up. And what it picks up often runs far beyond the explicit message. It may well include the results of highly invested attention to imagined subtexts that may have more impact on the receiver than the intended message. This is often astonishing and dismaying to leaders who cannot understand how subordinates could possibly have “made that sense out of this” communication, but because the receiver’s signal-to-noise detector may be highly distorted, the actual information that comes through may have only a distant relationship to the sender’s intention.

Self-Authoring Mind

Let’s contrast all this with the self-authoring mind. If I view the world from this level of mental complexity, what I “send” is more likely to be a function of what I deem others need to hear to best further the agenda or mission of my design. Consciously or unconsciously, I have a direction, an agenda, a stance, a strategy, an analysis of what is needed, a prior context from which my communication arises. My direction or plan may be an excellent one, or it may be riddled with blind spots. I may be masterful or inept at recruiting others to invest themselves in this direction. These matters implicate other aspects of the self. But mental complexity strongly influences whether my information sending is oriented toward getting behind the wheel in order to drive (the self-authoring mind) or getting myself included in the car so I can be driven (the socialized mind).

We can see a similar mindset operating when “receiving” as well. The self-authoring mind creates a filter for what it will allow to come through. It places a priority on receiving the information it has sought. Next in importance is information whose relevance to my plan, stance, or frame is immediately clear. Information I haven’t asked for, and which does not have obvious relevance to my own design for action, has a much tougher time making it through my filter.

It is easy to see how all of this could describe an admirable capacity for focus, for distinguishing the important from the urgent, for making best use of one’s limited time by having a means to cut through the unending and ever-mounting claims on one’s attention. This speaks to the way the self-authoring mind is an advance over the socialized mind. But this same description may also be a recipe for disaster if one’s plan or stance is flawed in some way, if it leaves out some crucial element of the equation not appreciated by the filter, or if the world changes in such a way that a once-good frame becomes an antiquated one.

Self-Transforming Mind

In contrast, the self-transforming mind also has a filter, but is not fused with it. The self-transforming mind can stand back from its own filter and look at it, not just through it. And why would it do so? Because the self-transforming mind both values and is wary about any one stance, analysis, or agenda. It is mindful that, powerful though a given design might be, this design almost inevitably leaves something out. It is aware that it lives in time and that the world is in motion, and what might have made sense today may not make as much sense tomorrow.

Therefore, when communicating, people with self-transforming min...