![]()

1

DESIGN-DRIVEN INNOVATION

[ An Introduction ]

With Metamorfosi, Artemide had completely overturned the reason why people would buy a lamp. Not another beautiful lamp, but a light that makes you feel better. It had radically changed its meaning. [IN THE ILLUSTRATION On the table: Artemide’s Yang lamp (of the Metamorfosi family); in the painting: Artemide’s Tizio “task luminaire.”]

MARKET? WHAT MARKET! We do not look at market needs. We make proposals to people.”

Without another word, Ernesto Gismondi, chairman of Artemide, stared at the professor to see his reaction. A strong personality and a brilliant mind, Gismondi was not the kind of person to be in awe of a major scholar, even one from a well-respected U.S. business school. We were enjoying a steamy risotto alla milanese at the restaurant Da Bice right in the center of Milan. The dinner followed a late afternoon visit to Artemide, a leading manufacturer of lamps, where I had taken a group of professors interested in the innovation process of design-intensive Italian manufacturers. Gismondi, who had a bad case of flu, had invited us to continue the discussion over dinner. At a certain moment one of the professors, a leading scholar in the management of innovation, asked him how the company had analyzed market needs to come up with a product we had seen earlier during the visit: Metamorfosi.

Metamorfosi, released in 1998, was a unique product that one would hardly call a lamp. The lighting industry typically conceives of lamps as modern sculptures. People usually choose them according to how beautiful they are and how well they fit into their living rooms. Taking for granted that lamps illuminate, competition concentrates on style. And Artemide had been a main protagonist, having created beautiful icons, such as Tizio in 1972.

Metamorfosi, however, was completely different. It was a sophisticated system that emitted an atmosphere created by colored light, which could be controlled and adapted according to the owner’s mood and need. Artemide’s vision was that ambient light—especially its color and nuances—has a significant influence on people’s psychological state and social interaction. The company therefore created a system that could emit a “human” light, a light that made people feel better and socialize better. The object itself was not even meant to be seen. Artemide had overturned the reason people bought a lamp. It had radically changed its meaning.

The interest of the American professor in this unique product was therefore legitimate, and the way he framed his question inevitable. In the business community worldwide, and especially in the United States, the imperative for success is user-driven or user-centered innovation. According to these approaches, companies should begin an innovation project by analyzing market needs, looking closely at users. Executives, MBA students, and designers are told repeatedly that the first thing they must do is take photos of how customers use products, to understand their unsatisfied needs. No one would dare question user-centered innovation.

Ernesto Gismondi’s answer, hence, was unexpected. It did not fall within the spectrum of answers the professor was contemplating (such as “Yes, we did some ethnographic analysis of people using lamps in their apartments and changing bulbs…”). It was so startling that the professor thought he had misunderstood because of the noise in the restaurant. Luckily, he did not ask the second question in his quiver (“Did you use brainstorming or other creativity-enhancing techniques?”), which would have provoked a similar answer. Instead he turned to another topic. Perhaps he thought Gismondi’s temperature was getting too high.

Gismondi, however, was of sound mind and his answer was loud and clear. And it could not have been different, because it perfectly suited the innovation strategy he was pursuing with Metamorfosi: a radical innovation of meaning.

The Strategy of Design-Driven Innovation

Two major findings have characterized management literature in the past decades.

The first is that radical innovation, albeit risky, is one of the major sources of long-term competitive advantage. For many authors, however, the phrase radical innovation is an ellipsis for a longer construction that spells radical technological innovation. Indeed, investigators of innovation have focused mainly on the disruptive effect of novel technologies on industries.

The second finding is that people do not buy products but meanings. People use things for profound emotional, psychological, and sociocultural reasons as well as utilitarian ones. Analysts have shown that every product and service in consumer as well as industrial markets has a meaning. Firms should therefore look beyond features, functions, and performance and understand the real meanings users give to things.

The common assumption, however, is that meanings are not a subject for innovation: they are a given. One must understand them but cannot innovate them. Meanings have indeed intensively populated the literature on marketing and branding. And user-centered perspectives have recently provided powerful methods for understanding how users (currently) give meaning to (existing) things. But in studies on radical innovation, an examination of meanings has been largely absent. They are not considered a subject of R&D.

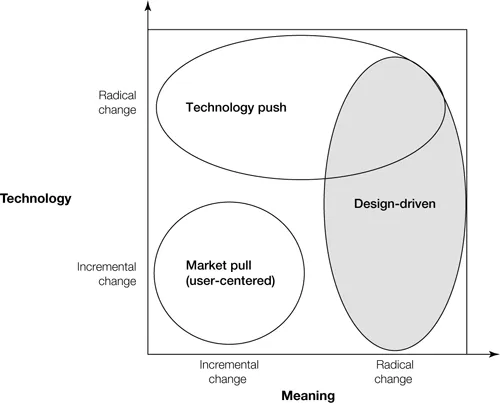

Innovation has therefore focused on two strategies: quantum leaps in product performance enabled by breakthrough technologies, and improved product solutions enabled by better analysis of users’ needs. The former is the domain of radical innovation pushed by technology, and the latter of incremental innovation pulled by the market (see figure 1-1).

Artemide has followed a third strategy: design-driven innovation— that is, radical innovation of meaning. It has not provided people with an improved interpretation of what they already mean by, and expect from, a lamp: a more beautiful object. Rather, the company has proposed a different and unexpected meaning: a light that makes you feel better. This meaning, unsolicited, was what people were actually waiting for.

Competing Through Radical Innovation of Meanings

Artemide is by no means alone in this strategy. Design-driven innovation is at the heart of numerous success stories of products and firms.

In November 2006, Nintendo launched the Wii, a game console with motion-sensitive controllers that allows people to play games by moving their bodies. For example, they might serve tennis balls by

FIGURE 1-1

The strategy of design-driven innovation as the radical change of meanings

circling their arms overhead or play golf by swinging their arms. Up to the moment the Wii was introduced, game consoles were considered entertainment gadgets for children who were great at moving their thumbs; they offered a passive immersion in a virtual world. And indeed, Sony and Microsoft further reinforced this meaning by developing the PlayStation 3 and the Xbox 360, consoles with more-powerful graphics and performance. The Wii overturned this meaning: it stimulated active physical entertainment, in the real world, through socialization. The intuitiveness of its controllers made it easy for everyone to play. The Wii transformed consoles from an immersion in a virtual world approachable only by niche experts into an active workout for everyone. People did not ask for that meaning, but they loved it once they saw it. Six months after the Wii’s release, sales in the U.S. market were double those of the Xbox 360 and quadruple those of the PlayStation 3. And even though the Wii was much cheaper than its competitors, its profitability was much higher.

The late 1990s witnessed the birth of the first MP3 players: MPMan and Rio PMP300. They were meant as portable music players: more-powerful substitutes for the popular Walkman, which used old technology—cassettes and CDs—to carry tunes. These MP3 players changed the technology but left its meaning untouched: listening to songs away from home. Market response was lukewarm. Apple, in contrast, proposed a completely different vision: enabling people to produce their own music. Between 2001 and 2003 it released a system of products, applications, and services that supported a seamless experience of discovering, tasting, and buying music (through the iTunes Store); storing and organizing music collections in personal playlists (through the iTunes software); and listening to it through the iPod (which became simply the player, even in homes). The business that Apple built on this proposal was stunning.

In 1980 a team of visionary lovers of good-tasting, healthy food opened a store destined to change the future of food retailing: Whole Foods Market. These visionaries focused on organic and natural food. When you entered other organic food stores, you felt as though you were an ascetic in a small sect doing penance, but Whole Foods Market celebrated pleasure. Not only did labels and posters educate consumers about the virtues of natural and organic foods, health, nutrition, and sustainable agriculture, but also produce was arranged as if on a stage: an irresistible party of colors and smells. Whole Foods Market has radically changed the meaning of healthy nutrition from a severe, self-denying choice to a hedonic one, and shopping from a chore to a reinvigorating experience. (New services even allow people to get a massage while a grocery valet takes care of the shopping list.) Whole Foods Market is the fastest-growing company in the competitive grocery business.

Everyone knows that corkscrews are meant to pull corks and that citrus squeezers are meant to squeeze lemons. These are tools; thus innovation has always aimed at making them more functional or more beautiful. In 1993 Alessi, a manufacturer of household items, released a new family of products that were not necessarily more functional and did not comply with existing standards of beauty. This family included a series of playful plastic objects, most with an anthropomorphic or metaphoric shape, such as Mandarin, a citrus squeezer stylized as a Chinese mandarin in a conical hat, and Nutty the Cracker, a nutcracker in the shape of a squirrel whose teeth crack the shells. Shallow observers labeled the family a fanciful, crazy idea—the output of extemporaneous and useless creativity. But that wasn’t the case. The product line was the result of years of serious research aimed at proposing a radical new meaning: household items as objects of affection, as substitutes for teddy bears for adults. Rather than talk to the little engineer or the little stylist inside each of us, Alessi was talking to our inner child. This unsolicited meaning turned out to be exactly what people were looking for. During the past fifteen years this vision has inspired many companies beyond the kitchenware industry to pursue now-popular emotional design. Meanwhile Alessi has enjoyed double-digit annual growth.

Companies such as Artemide, Nintendo, Apple, Whole Foods Market, Alessi, and many others I discuss in this book show that meanings do change—and that they can change radically. The design-driven innovations introduced by these firms have not come from the market but have created huge markets. They have generated products, services, and systems with long lives, significant and sustainable profit margins, and brand value, and they have spurred company growth.

An Unexplored Conundrum

The reason Gismondi’s “proposals to people” assertion sounds surprising to many practitioners and scholars is simply that we know little about how design-driven innovation occurs. Years of research have yielded several compelling explanations for technological breakthroughs, but no theory about how to manage radical innovation when it comes to meanings. It’s a conundrum enshrouded in mystery.

In 1998, returning to Politecnico di Milano after a period at Harvard Business School investigating the management of breakthrough innovations in Internet software, I had the chance to become involved in two major projects. One was Sistema Design Italia (Italian Design System), a first-ever research project on the economics and organization of design processes in Italy.1 The other project was the creation, at Politecnico di Milano, of a graduate school of industrial design, the first ever in Italy. I seized both opportunities enthusiastically. Italy was quite weak in software but an acknowledged worldwide leader in design, especially in industries such as furniture, lighting, and food.

I was especially attracted by the fact that the success of Italian design is rooted in manufacturers rather than designers. (Indeed, foreign designers actually perform much of so-called Italian design: innovative Italian furniture manufacturers hire about 50 percent of their designers from abroad.) The secret of Italian design was concealed in the hands of entrepreneurs and executives, making this empirical ground particularly interesting for management studies.

The most distinctive and advanced firms in this regard are concentrated in northern Italy, in industries that deal with domestic lifestyle. Many of these companies, such as Artemide, Alessi, Kartell, B&B Italia, Cassina, Flos, and Snaidero, are industry leaders despite their small size (only the latter has more than five hundred employees). They have built their leadership on innovation, and not on complementary assets such as distribution, market penetration, and low labor costs. Between 1994 and 2003, in an industry where other Western companies considered themselves lucky if they had any growth (EU furniture manufacturers grew 11 percent over that decade), the revenues of these companies grew between 54 percent (B&B Italia) and 211 percent (Kartell).

Even more interesting, these firms had a unique innovation strategy. Contrary to common wisdom, their success was not related simply to their capacity to create beautiful objects. Rather, they often moved against the dominant aesthetic standards, as the Artemide and Alessi examples clearly show. What made these firms different from many others that use design for styling or user-centered innovation was that they were leaders in the radical innovation of meanings.

The Italian design system therefore proved to be a unique empirical setting for investigating the management of design-driven innovation. I was lucky. However, the research proved much more painful than I had expected, revealing why design-driven innovation had remained unexplored.

First, companies that are very successful at design-driven innovation are not really open to someone who wants to investigate their process, especially if he is a management scholar. As you will see, their model is based on elite circles, which admit novices only if they bring interesting knowledge. Unfortunately, existing management theories are so far removed from the strategies of these firms that they see almost no utility in them. It took me literally years to gain their trust, to be admitted into the circle and gain access to their processes. Luckily, the two projects in which I...