eBook - ePub

Beyond Budgeting

How Managers Can Break Free from the Annual Performance Trap

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond Budgeting

How Managers Can Break Free from the Annual Performance Trap

About this book

The traditional annual budgeting process--characterized by fixed targets and performance incentives--is time consuming, overcentralized, and outdated. Worse, it often causes dysfunctional and unethical managerial behavior. Based on an intensive, international study into pioneering companies, Beyond Budgeting offers an alternative, coherent management model that overcomes the limitations of traditional budgeting. Focused around achieving sustained improvement relative to competitors, it provides a guiding framework for managing in the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond Budgeting by Jeremy Hope, Robin Fraser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Promise of Beyond Budgeting

Chapter One

The Annual Performance Trap

Uncertainty—in the economy, society, politics—has become so great as to render futile, if not counterproductive, the kind of planning most companies still practice: forecasting based on probabilities.1

—PETER DRUCKER

Like them or loathe them, everyone has a view about budgets. CEOs like the warm feeling they get when they see the year-end profit forecasts. But they might be anxious about the reliability of the assumptions and the firm’s ability to respond to change. CFOs like the way they are able to tie operating managers to fixed performance contracts (fixed targets reinforced by incentives). But they also know that the process takes too long and adds too little value. Operating managers like “knowing where they stand.” But they are also concerned about the time wasted and, more important, that fixed performance contracts lead to decision paralysis and cosmetic accounting rather than decisive action and ethical reporting.

Though this ambivalence toward budgeting has existed for decades, the balance of opinion has swung decidedly in favor of the “very dissatisfied.” Even within the financial management community, nine of ten have expressed their dissatisfaction, finding the budgeting process too “unreliable” and “cumbersome.”2 According to a recent cover article in Fortune magazine, around 70 percent of companies surveyed were poor at executing strategy—a massive indictment of the performance management capabilities of budgets.3 It turned out that most companies were characterized by incremental thinking, sclerotic budgeting processes, centralized decision making, petty operating rules, and controllers who demanded answers to the wrong questions. It is perhaps not so surprising that financial directors now rank budgetary reform as their top priority. 4 We will examine why these high levels of dissatisfaction have arisen in a moment. First, we must define what we mean by “budgeting.”

One recent management accounting textbook defined a budget as a “quantitative expression of the money inflows and outflows to determine whether a financial plan will meet organizational goals.”5 But such a plan is the result of a protracted process. We have used a broader definition, one that defines budgeting not so much as a financial plan but as the performance management process that leads to and executes that plan. So when we use the word budgeting from here on, we mean the entire performance management process. This process is about agreeing upon and coordinating targets, rewards, action plans, and resources for the year ahead, and then measuring and controlling performance against that agreement. This process, the resultant negotiated fixed performance contracts, and their impact on management behavior are the focus of attention in this book.

How have we arrived at such high levels of dissatisfaction with budgeting? There are three primary factors: (1) Budgeting is cumbersome and too expensive, (2) budgeting is out of kilter with the competitive environment and no longer meets the needs of either executives or operating managers, and (3) the extent of “gaming the numbers” has risen to unacceptable levels. These problems have not happened overnight. Budgeting has been a festering sore for many decades, but its problems have, by and large, been swept under the carpet. It has taken the rapid changes in the competitive climate of the 1990s and the corporate governance scandals of 2001—2002 to expose them fully.

Budgeting Is Cumbersome and Too Expensive

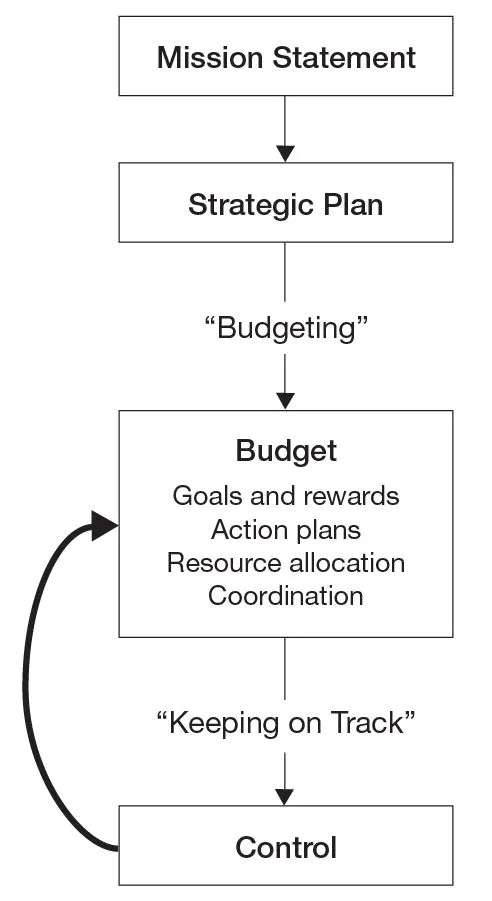

For most participants, the budgeting process is an annual ritual that is deeply embedded in the corporate calendar. It absorbs huge amounts of time for an uncertain benefit. It typically begins at least four months prior to the year to which it relates. As figure 1-1 illustrates, it starts with a mission statement that sets out some of the aims of the business. This is followed by a group strategic plan that sets the direction and high-level goals of the firm. These form the framework for a budgeting process that grinds its way through countless meetings at which points are traded as targets are negotiated and resources agreed upon.

It starts when budget “packs” are sent out from the corporate center to operating divisions and departments, accompanied by forms to be completed that include sales, operational, and capital expenditure forecasts. For a whole business unit, the bottom line will be a profit and cash flow forecast for the year ahead. Once completed, these packs are returned to the corporate center (or to intermediary points in the hierarchy) and then subjected to review. Thereafter multiple iterations take place as each unit negotiates the final outcome. Once the budget is agreed upon, regular reports are required by the corporate center to enable senior executives to control performance.

FIGURE 1-1

The Traditional Budgeting Process

Despite the advent of powerful computer networks and multilayered models, this process remains protracted and expensive. The average time consumed is between four and five months.6 It also involves many people and absorbs up to 20 to 30 percent of senior executives’ and financial managers’ time.7 Some organizations have attempted to place a cost on the whole planning and budgeting process. Ford Motor Company figured out this amounted to $1.2 billion per annum.8 A 1998 benchmarking study showed that the average company invested more than 25,000 person-days per billion dollars of revenue in the planning and performance measurement processes.9

The perception of the value provided by the budgeting process varies widely. In one firm we visited it was apparent that the group board thought the budget gave them control, whereas operating managers thought it was completely irrelevant to their needs. One of the primary reasons that financial directors rank budgetary reform as their highest priority is that their staffs spend too little of their time adding value. One conclusion from a 1999 global best practices study was that finance staff spent 79 percent of their time on “lower value-added activities” and only 21 percent of their time analyzing the numbers.10 Nor does it help when hard-pressed managers have to wait eleven days into the following month before they can compare monthly management accounting results with the budget.11

For any firms involved in mergers, acquisitions, disposals, and other reorganizations, the budgeting workload can be overwhelming. The result is a finance team under constant pressure to reconfigure the numbers rather than support hard-pressed managers with the information they need to make decisions. A few comments in a recent survey of U.S. accountants are telling. “We have just been burning people out. They have been working incredible hours.... They are giving up family life.... We are all concerned.”12

Budgeting Is Out of Kilter with the Competitive Environment and No Longer Meets the Needs of Either Executives or Operating Managers

If you had asked senior executives in the 1970s what they wanted from their management processes, they would likely have emphasized the need to set reasonable return-on-capital targets and then formulate detailed and coordinated plans for the year ahead to meet them. Executives would have expected compliance with these plans throughout the organization, supported by tight cost control and measures geared to monitoring performance against the plan. In other words, they expected to plan, coordinate, and control their operations from the corporate center.

The budgeting process was tailor-made for the job (although it was already becoming cumbersome and expensive). IBM was a classic example. In 1973 its planning bureaucracy had grown to three thousand people and its “annual” planning process approached an eighteen-month cycle.13 But it played a part in enabling the company to become the dominant player in the global computer market. Its ability to design, make, and sell its computer hardware and software to compliant customers was supreme. Every division, business unit, and individual salesperson knew from their performance contracts what they had to achieve in the year ahead. Growth and prosperity seemed unstoppable.

The oil price increases and subsequent inflationary pressures of the mid-1970s changed the competitive climate. Leaders became concerned about rising costs. Bloated bureaucracies and their associated fixed costs were a key factor, and a number of managers began to realize that the budgeting process failed to challenge them. One solution promoted by consultants was called zero-base budgeting (ZBB). ZBB starts with a blank sheet of paper in regard to discretionary expenditure. It proved to be a useful (though usually one-off) exercise to review discretionary overheads. However, the process was so bureaucratic and time-consuming that few companies used it more than once. Moreover, like traditional budgeting, it was based on the organizational hierarchy. It thus reinforced functional barriers and failed to focus on the opportunities for improving business processes.

In the late 1980s, IBM stumbled badly as it misread the personal computer revolution and found itself surrounded by more nimble competitors with lower costs. Like many other firms, it had to make tough decisions as it faced gut-wrenching changes, or it would fail to survive. Discontinuous change had become the norm (see figure 1-2).

From the 1980s onward, uncertainty increased and the pressures on corporate performance became more intense. Shareholders were demanding that firms be at or near the top of their industry peer group on a range of measures. Intellectual capital such as brands, loyal customers, and proven management teams had risen to be the primary drivers of shareholder value. Product and strategy cycles had shortened, emphasizing the need to continuously innovate. Prices and margins were constantly under pressure, requiring action to slash structural costs and reduce bureaucracy. And customers were increasingly fickle, calling out for more decentralized authority to enable front-line people to respond to changing customer needs. Moreover, “command and control” had become a pejorative term for an outdated management style. Leaders had recognized that to become more “agile” or “adaptive” meant transferring more power and authority to people closer to the customer.

FIGURE 1-2

The Changing Business Environment

In these turbulent times the budgeting process struggled to cope. Goals and measures were internally focused. Intellectual capital was outside the orbit of the budgetary control system. Innovation was stifled by rigid adherence to fixed plans and resource allocations agreed to twelve to eighteen months earlier. Costs were fiercely protected by departmental managers who saw them as budget entitlements rather than scarce resources. The internal focus on maximizing volume collided with the external focus on satisfying customers’ needs. And far from being empowered to respond to strategic change, front-line people found that it was easier to do nothing than to try to get multiple signatures on a document authorizing a change in the plan.

Many firms responded to changes in the competitive climate by introducing more frequent and streamlined planning and budgeting processes. These included budgets done half-yearly or quarterly instead of annually, and “rolling budgets” that tended to have a twelve-month horizon (updated every quarter). Though these approaches offered more current (and thus more relevant) numbers for managers to follow, they suffered from an increased workload (even if done with fewer line items) and thus, more often than not, even higher cost.

Implementing strategic management models such as the Balanced Scorecard was another approach taken by an increasing number of firms that tried to shift their emphasis from being “budget-focused” to being “strategy-focused” organizations. The Balanced Scorecard is one of the most innovative tools to emerge in recent years and offers organizations a robust framework for overcoming many of the problems we have just outlined. But its full power is too often constrained by the short-term performance drivers of the annual budget. These remain focused on “managing” the next year-end rather than supporting medium-term strategy. Indeed, the evidence from Scorecard users is that, far from transforming their companies into strategy-focused organizations, they have simply added some strategic indicators to their annual budgets. Scorecard indicators, according to a 2002 global survey, remained predominantly financial (62 percent) and lagging (76 percent).14 Moreover, in many cases, Scorecard targets are compared with actuals, and variances are reported in a similar way to the traditional budget.

Few of the innovative management tools of the past decade have been used to fundamentally transform the performance management process. At best they have made marginal improvements to a broken system. At worst they have had negative effects as they...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Toward a New General Management Model

- Part I - The Promise of Beyond Budgeting

- Part II - The Adaptive Process Opportunity: Enabling Managers to Focus on Continuous Value Creation

- Part III - The Radical Decentralization Opportunity: Enabling Leaders to Create a High Performance Organization

- Part IV - Realizing the Full Promise of Beyond Budgeting

- Glossary

- Notes

- Index

- About the Authors