![]()

1

WHAT COLLECTIVE GENIUS LOOKS LIKE

We're not just making up how to do computer-generated movies, we're making up how to run a company of diverse people who can make something together that no one could make alone.

—Ed Catmull, cofounder, Pixar, and president, Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios

Why are some organizations able to innovate again and again while others hardly innovate at all? How can hundreds of people at a company like Pixar Animation Studios, for example, produce blockbuster after blockbuster over nearly two decades—a record no other filmmaker has ever come close to matching? What's different about Pixar?1

This question is crucial. In a time of rapid change, the ability to innovate quickly and effectively, again and again, is perhaps the only enduring competitive advantage. Those firms that can innovate constantly will thrive. Those that do not or cannot will be left behind.

Pixar released Toy Story in 1995, the first computer-generated (CG) feature film ever produced. Since then, as we write this, it has released fourteen such movies, including Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3; A Bug's Life; Monsters, Inc.; Finding Nemo; The Incredibles; Cars; Ratatouille; Wall-E; Up; Cars 2; Brave; and Monsters University. Virtually all have been critical, financial, and technological successes. The winner of numerous awards, including twenty-six Academy Awards, Pixar is one of those rare studios that command the respect of filmmakers, technologists, and businesspeople alike.

CG movies are mainstream today, but Pixar's founders took two decades to realize their dream of creating a feature-length CG film. After years in academia, Ed Catmull and a handful of colleagues joined Lucasfilm, where Catmull led the effort to bring computer graphics and other digital technology into films and games. Catmull and team pushed the boundaries of what could be done, securing patents and providing producers like Steven Spielberg with the tools to create scenes like those of the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. Ultimately, however, the division was too costly for George Lucas. In 1986, Steve Jobs bought it for $10 million, and Pixar Animation Studios was born.

Pixar has survived since then only because it has been consistently inventive. Every film it produced has been an innovative tour de force. But conventional wisdom about innovation cannot explain its extraordinary accomplishments. No solitary genius, no flash of inspiration, produced those movies. On the contrary, each was the product of hundreds of people, years of work, and hundreds of millions of dollars.

What has allowed Pixar to accomplish what it's done? We begin to see at least part of the answer in a personal comment by Catmull, the computer animation pioneer who cofounded and then led the studio as it produced hit after hit:

For 20 years, I pursued a dream of making the first computer-animated film. To be honest, after that goal was realized—when we finished Toy Story—I was a bit lost. But then I realized the most exciting thing I had ever done was to help create the unique environment that allowed that film to be made. My new goal became … to build a studio that had the depth, robustness, and will to keep searching for the hard truths that preserve the confluence of forces necessary to create magic.2

What Catmull discovered in making Toy Story was the critical role of leadership in creating an organization or context that fostered and enabled innovation. He understood innovation could not be compelled or commanded. Indeed, this most voluntary of human activities could only be, to use his word, “enabled.”

To understand what Catmull and other effective leaders of innovation do, we begin by looking at what collective genius looks like. For that, there's no better example than Pixar, because most of us have seen at least one Pixar movie. So when we describe all the individual slices of genius that go into making a CG film, you will be able to appreciate the difficulty of converting those slices into the collective genius you see on the theater screen.

What Pixar does may seem different from the work of most other organizations. Certainly, the product it makes is different. But think of any other firm that offers a product or service that no individual could provide alone. Clearly, such a firm must grapple, in form though not substance, with the same kinds of challenges Pixar has had to overcome in every film it's made. Every example of innovative problem solving embodies exactly what Catmull described: hundreds and even thousands of ideas from many talented people.

How Pixar Innovates

Innovation is the creation of something both novel and useful. It can be large or small, incremental or breakthrough. It can be a new product, a new service, a new process, a new business model, a new way of organizing, or a new film made in a new way.

Whatever form innovation takes, people often think of it as a chance occurrence, a flash of insight, a brainstorm by one of those rare individuals who's “innovative” or “creative.” It can be, but most often such things play no role or only minor roles, and the actual process of innovation is more complex. This becomes crystal clear when we return to Pixar and look more closely at how it works.

Making a CG movie

Some have said that creating a CG animated film is like writing a novel because both start with a blank slate. The creator can do whatever he or she can imagine. Blow up the world? No problem. Hop over the Grand Canyon? Easy. In making a CG film, however, that freedom comes with a price. Everything in the film—everything, down to the tiniest speck of dust or the subtle flow of a shadow across a character's face—must be consciously chosen, created, and inserted by one of the hundreds of people involved. Every piece of it must be created, invented, innovated.

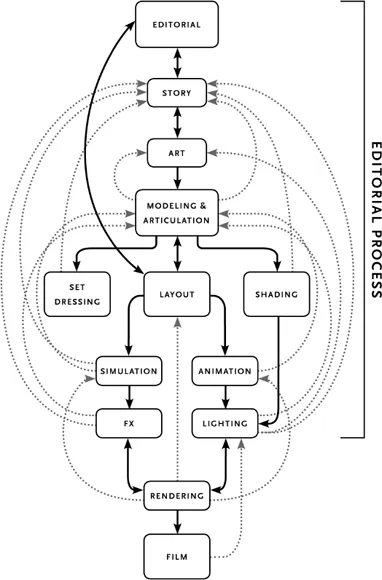

To explain the process in simple terms, we use a diagram produced by Greg Brandeau based on his experience running the systems group at Pixar (see figure 1-1).

Each block in the diagram represents not only a stage in the process but a group of highly talented people who perform some essential task.

The process begins with a director who has an idea for a story. He works with people in the story department over twelve to eighteen months to flesh out the tale in words and drawings, usually through many revisions. From the idea, they create a treatment or description of the story. From that, they produce a script. Once the script is approved, they put together thousands of individual storyboards (images) that are in turn cut together to produce reels. Meanwhile, the art department begins to work on the look and feel of the characters and film in general. The film's editor works with the director to cut together the storyboards and create reels that link together the art, dialogue, and temporary music. These reels are updated, revised, and refined as the production progresses. Now the work passes into the hands of various groups of artist-technicians who use sophisticated design software to create the thousands of digital elements that compose the final film. One group creates three-dimensional digital models of the story characters. Another builds and shades the digital settings—a bedroom, a racetrack, a city—where movie scenes will be placed and “shot.” Another creates and places the digital objects—tables, chairs, books, beds—that appear in every scene. The layout group—the CG equivalent of cinematographers—roughs out how characters and objects will be shot as they move through each scene. Lighting specialists specify how light appears to fall in each scene. Animators specify the exact movements of characters in every scene to show not only what they do but also how they feel—happy, afraid, or angry, for example.

That's complicated enough, but there's even more. Yet another group creates the texture of surfaces, such as skin or hair, and how light interacts with the surface, which can be a major problem for a computer to recreate realistically. Simulators produce digital versions of various natural phenomena, such as hair blowing in the wind or the way a piece of loose clothing falls and drapes as a character moves. Special-effects specialists depict objects that move in complex ways, such as falling snow, wind, flames, sparks, and water. In the final step, called rendering, hundreds of computers run by systems experts use all the instructions created in earlier steps to compute each individual movie frame. At twenty-four frames per second, a feature film contains well over a hundred thousand frames, and each frame—every one of them—can require up to several hours of computer processing.

Reducing all this to a diagram seems to imply that producing a CG film is a simple series of steps these different groups take in a neat, sequential way. It fails to communicate how iterative and interrelated—in short, how messy—the steps of the process are, because the story can and usually does evolve throughout the making of the film. As it's being made, the thousands of digital objects in it, linked into shots and scenes, move through the production pipeline, but not in order. Different shots and scenes move through at different times and even at different rates. Some move quickly, while others take months or longer because they present difficult artistic and technical challenges, large and small, that require the joint efforts of many groups to resolve. For example, one gifted animator took six months to get ten seconds of the film Up right. Almost nothing is simple and straightforward.

For that reason, we often present a slightly different version of the diagram that reflects its inherent messiness. In concept, this is the same as the previous diagram except it shows all the feedback loops and multiple iterations that actually occur (see figure 1-2). No wonder CG films require so much time (years), money (hundreds of millions of dollars), and the creative exertions of so many people (200–250) to make.

The analogy we drew earlier between making a CG film and writing a novel is fundamentally flawed. It would only apply if a novel were written not by one author but by hundreds of people, some in charge of the story, some others in charge of nouns, some in charge of adjectives, some in charge of sentences, some in charge of paragraphs, and some in charge of chapters. Yes, every movie has a director—in effect, the master storyteller, the one with the overall creative vision for the movie—who determines what is ultimately seen and heard on the screen. But it's impossible for the director, or any other individual, to specify everything that must be invented to make a CG film. She must rely on the creativity of everyone involved.

As Catmull said, each Pixar film “contains tens of thousands of ideas.”

They're in the form of every sentence; in the performance of each line; in the design of characters, sets, and backgrounds; in the locations of the camera; in the colors, the lighting, the pacing. The director and the other creative leaders of a production do not come up with all the ideas on their own; rather, every single member of the 200- to 250-person group makes suggestions. Creativity must be present at every level of every artistic and technical part of the organization.3

Now, with your understanding of how Pixar makes movies, put yourself in a theater and imagine you're watching a Pixar movie—the final outcome of this long, complicated, arduous process. What do you actually see and experience? The engaging images and sounds flow by seamlessly, as though created effortlessly by a single master storyteller. Every part fits into a coherent whole. There's no indication of the process or the many disparate individuals who created what you're watching.

In this contrast between the simple coherence of the outcome and the complexity of the process that produced it, we can see the ultimate challenge of all organizational innovation: to create a coherent work of singular collective genius from the diverse slices of genius brought to the work by all the individuals involved. This is what all innovative organizations are able to do well, over and over.

Talent is critical, of course. Conventional wisdom at Pixar says that great people can turn a mediocre idea into a great movie, while mediocre people will ruin even a great idea. But the ultimate challenge of innovation extends far beyond finding creative people. Pixar does have such people; it works hard to find and keep them. Unlike most film studios, which hire talent movie by movie, Pixar hires employees who stay and work on movie after movie. But Pixar certainly doesn't employ the only talented people in the world. Any organization that wants to innovate again and again must do more than hire a few “creative individuals” because, even with the right people, there's still the huge problem of getting them to work together productively.

That is the job of leaders who seek innovation. In the way they behave and structure an organization where talented people work, leaders create the environment that somehow draws out the slice of genius in each individual and then leverages and melds those many slices into a single work of innovation—a new product, a new process, a new strategy, a new film—that represents collective genius. This is what happens when organizations innovate.

Leading Innovation

Though each of our leaders and their firms differed in key ways, all leaders paid particular attention to making sure their organizations were able to:

- Collaborate

- Engage in discovery-driven learning

- Make integrative decisions

Our leaders' uniform emphasis on fostering these three capabilities will not surprise anyone familiar with existing research on innovative problem solving. Much evidence exists for the importance of each. However, they have been most often studied separately. Because our focus was on leadership in action, we were able to observe how these three interrelated organizational skills work in concert as leaders and their groups undertake to create something novel and useful. Based on those observations, we have developed an integrated framework for understanding, describing, and prescribing how leaders build organizations capable of consistent innovation by focusing on these essential abilities.

Leaders create collaborative organizations

Lore perpetuates the myth of innovation as a solitary act, a flash of creative insight, an Aha! moment in the mind of a genius. People apparently prefer to believe in the rugged individualism of discovery, perhaps because they rarely get to see the sausage-making process behind every breakthrough innovation.

Three decades of research has clearly revealed that innovation is most often a group effort.4 Thomas Edison, for example, is remembered as probably the greatest American inventor of the early twentieth century. From his fertile mind ca...