![]()

Chapter 1

Ely

‘Ship of the Fens’: the magic and majesty of Ely Cathedral

Ely Cathedral (© Bernadette Fallon)

Known as the ‘Ship of the Fens’, Ely Cathedral rises majestically from the surrounding landscape. Once it stood on an island, surrounded on all sides by water, but the draining of the marshland several centuries ago reunited the land around the cathedral with the rest of the countryside. It still retains some of that other-worldly allure, however, and today rises magically from the early morning mists.

Its origins are also somewhat magical and unusual because Ely Cathedral was founded by a woman. She was Etheldreda, an Anglo-Saxon princess of the 7th century and the daughter of the King of East Anglia. Being a woman, her marriage was used to make a political alliance and Etheldreda in fact was used to make two.

She married her first husband Tondberht in the mid-600s and at some point was given the isle of Ely, perhaps as a mourning gift on the death of her husband. She remained a virgin throughout her marriage and afterwards came to the island to live.

Next, she was given in marriage to Egfrith, Prince of Northumberland, and lived with his Aunt Ebba at Kirkwall Priory in Northumbria. But once he became king the marriage ended, though the reasons for this are unclear – perhaps because she refused to consummate it. Now Etheldreda, advised and aided by Wilfrid, Bishop of Northumbria and founder of Ripon Cathedral, became a nun.

In the later part of the 7th century she returned to Ely, a journey of 300 miles, and established an Anglo-Saxon church there. Local legend has her placing her staff in the ground and, discovering a tree to have grown there the next morning, founding a monastery on this spot. Though it’s probably worth noting that while trees in fact do grow very quickly in the Fens, it generally doesn’t happen overnight.

Etheldreda lived here until she was 49, when she died from the effects of a large tumour on her neck, thought to have been caused by the plague. Buried outside the monastery, her successor ordered the coffin to be moved inside, at which point it was discovered that the plague marks on her neck had mysteriously healed and her body was incorrupt. She looked, according to records, as though she had fallen asleep. She had been a healer in her lifetime and many healing miracles were reported after pilgrims visited her relics, so she was canonised a saint.

Etheldreda’s monastery was plundered by Vikings in the 9th century. However, an account written in Liber Eliensis says that when the Vikings tried to open Etheldreda’s coffin to reach her relics, the lid splintered and blinded them. The famed Liber Eliensis tells the history of the area and was written by a monk of Ely monastery in the 12th century.

A Benedictine monastery was established in 970 with a stone Saxon church that occupied part of the site of the present cathedral, and in 1081 the great cathedral itself was started by the Normans, following William the Conqueror’s victory at the Battle of Hastings. A monk, Abbot Simeon, was responsible for the early work despite his great age (he was 87). He lived for another twelve years afterwards, which the locals like to attribute to the good quality water and famous Ely eels.

As was common, building at Ely started at the east end and it took 108 years to reach the west wall. Although it has plenty of trees and timber, East Anglia is lacking in stone and so the stones for the cathedral had to be sailed down the waterways from Barnack quarry, 60 miles away, a long journey by water.

In the 13th century, a major new addition to the building was constructed at the east end to accommodate St Etheldreda’s shrine and the huge crowds of pilgrims who continued to flock to visit her relics. The shrine continued to be a focal point for pilgrims right up to the Reformation, when it was destroyed with Ely’s other famous relics – the cathedral was known to hold the shrines of three other female saints and many bishops.

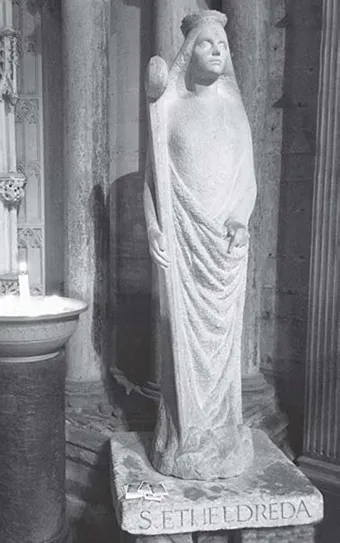

Today St Etheldreda’s Chapel is marked by a modern statue made in the 1960s by Philip Turner. And while nothing remains here of her relics, reportedly her hand ended up in London, in St Etheldreda’s Church in the capital’s Ely Place, the London home of the bishops of Ely. And this hand eventually made its way back to Ely, to St Etheldreda’s Roman Catholic church in the 1950s.

But despite the fact no relics remain and the building is no longer the Catholic place of worship she founded, procession pageants and festivals held every year on her feast days, 23 June and 17 October, still keep some of the old Catholic traditions alive.

St Etheldreda (© Bernadette Fallon)

On the north side of the cathedral, the Processional Way follows the path of the medieval passageway that pilgrims used to travel from the shrine to the Lady Chapel. It was dedicated in the year 2000 and is the first substantial addition to the cathedral since the 14th century. It allows today’s visitors to travel the same much-trodden path as their medieval counterparts.

Don’t miss: the beauty created from destruction

In the 14th century, Ely’s mighty Norman central tower came crashing down, a traumatic event for the monks who had just returned to bed after morning Matins at 4.30am. The noise of its fall was so great that the monks thought there had been an earthquake, but miraculously, given that they had been so lately at the scene of the disaster, nobody was injured.

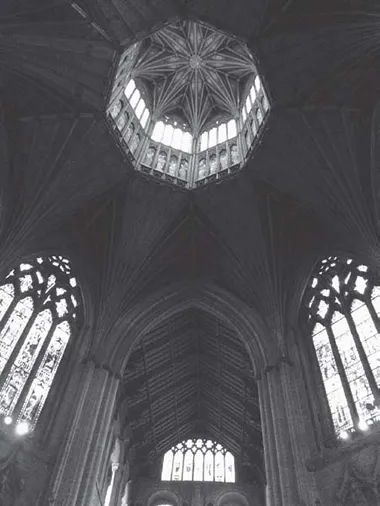

Out of destruction rose one of the most beautifully defining features of this, or in fact any, cathedral, the masterpiece of medieval engineering that is the octagon and lantern. It frames the central space high above the nave with a dazzling display of elegantly executed arches, painted panels and detailed carving. It is built in wood and covered in lead, 170 feet high and 71 feet wide, and the lantern itself weighs 400 tonnes.

Far above, the carved figure of Christ in majesty looks down from the central point of this wondrous creation. He might look small from below, but this mighty carving is estimated to measure 4 by 6 feet. Carved by local craftsman John of Burwell, a village south east of Ely, we know he was paid 2 shillings plus bed-and-board from the monks while he worked on it.

Curious facts: the suspended tower

The lantern is formed by columns of oak trees that are 63 feet long, and some of the wooden angel panels around the edge are actually doors that open and close. It took twenty years to build and one of the many fascinating facts about its construction is that it is not nailed or screwed together in the conventional way but held in place by wooden pins that fit into adjoining pieces, all suspended in space.

Don’t miss: the octagon tour

You can take a tour up into the octagon and beyond, right out onto the roof itself. It’s definitely a trip worth taking, with a chance to peer down from the open angel doors into the centre of the building and get a close-up view behind the scenes at the wonders of medieval manufacturing. And, of course, amazing views across the countryside from the roof of the building and a chance to clamber over medieval workmanship.

The Octagon (© Bernadette Fallon)

Up in the lantern you come face-to-face with the mighty oak trees that were already 300 years old when they were felled 700 years ago. Eight posts form the main structure of the lantern. The cost of the oak trees for the entire job came to £9, a substantial sum back then when you consider the poor craftsman who carved the central Christ was only paid 2 shillings for his contribution. Though, of course, creating this beautiful sculpture would have brought him great honour and glory.

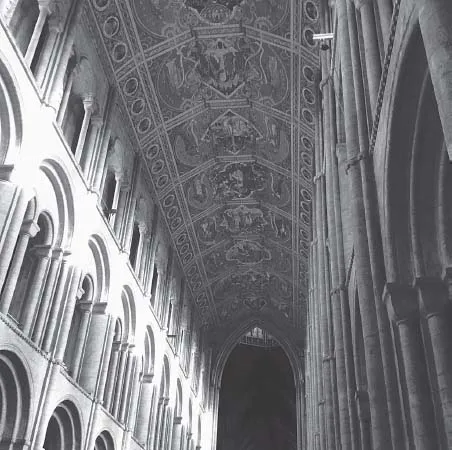

Ely nave (© Bernadette Fallon)

Up here behind the scenes you can see the Victorian repairs that have been made to sustain the tower’s great weight, using lead and iron rods to strengthen the structure. And keep an eye out for the tower’s graffiti, from the original medieval builders and legions of visitors over the centuries, including those who fought in the First and Second World Wars. In the 1940s, squadrons would gather over the cathedral in their Halifaxes, Lancasters and Wellingtons before they began their journey into German skies. For many who never came back, Ely Cathedral was their last view of home.

Back down in the nave, take some time to admire its rather spectacular ceiling. Richly painted and decorated, it was installed as part of the Victorian restoration and tells the story of the ancestry of Jesus. The wood is Russian pine, sourced from St Petersburg for the job. The artists who worked on this prestigious project offered their services for free.

Curious facts: the locals in the ceiling

Henry Styleman le Strange painted the first six ceiling panels from the west end. He modelled some of the faces in the ceiling on the cathedral staff and also included his own likeness in the paintings. Then tragedy struck. He went to assess a job in London, died suddenly, and the ceiling was left half-finished. It was up to the dean of the day, Harry Godwin, to find a replacement who would also work for free and finish the final six panels. Thomas Gambier Parry took on the job.

The north and south transepts contain fine examples of Norman stonework, including the small relief carvings on the capitals that are some of the earliest Norman sculptures in England. Later architectural additions to the space include the 15th century hammer-beam roofs decorated with flying angels and a Victorian restoration of the original painted decoration on the arches.

The 14th century quire was rebuilt in a style similar to the new octagon after the collapse of the tower. This was a development of the Early English style known as Decorated Gothic, ornate and richly embellished. The work was carried out under Bishop John Hotham who paid for it out of his own personal funds, a total sum of £2,034 12s 8¾d. The rear rows of the stalls also date from the 14th century, with their carved misericords, while the front stalls are Victorian and include some wonderful angel carvings.

Curious facts: the fickle Bishop Goodrich

Though his dissolution of the monasteries and Reformation destroyed both the lifestyles and internal fabric of churches throughout the land, Henry VIII did set-up a fund for ‘twelve scholars of some ability’ to sing for the services in Ely, the origin of today’s Kings School.

And Henry had help implementing the destruction, of course. While many buildings were desecrated by his soldiers or later under Oliver Cromwell during the Civil War, sometimes the work was carried out by the local clergy. Ely’s Bishop of the time, Thomas Goodrich, was a bit of a fair-weather clergyman, switching his allegiance from Catholic to Protestant under Henry VIII, and back again to Catholic under Mary. He was keen to carry out the king’s work in the cathedral, issuing an edict for the destruction of all statues, paintings and stained-glass in the cathedral in 1541.

We know that the cathedral once boasted over thirty chantry chapels, though only the records of them exist today. And in the Lady Chapel alone there were 140 medieval statues. So it’s therefore ironic that Bishop Goodrich’s own tomb, a fine brass memorial near the entrance to the quire, is roped-off to protect it from damage.

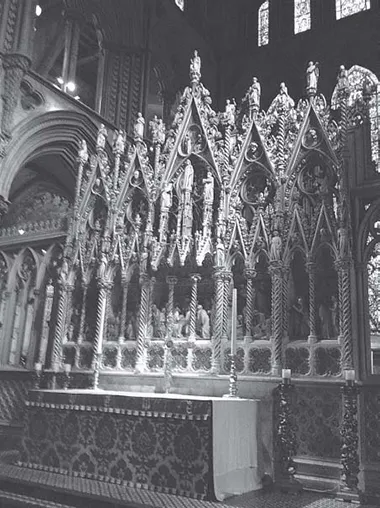

Victorians did enjoy a bit of ornamentation, as the Italian-style reredos behind the High Altar in the Presbytery aptly demonstrates. It was designed by George Gilbert-Scott, the architect of the 19th century restoration, and its five panels recount the events of Holy Week, the last week of Jesus’s life in the run-up to what is now celebrated as Easter. Erected in 1845, it is made from a single piece of Italian marble and took eleven years to carve.

Ely reredos (© Bernadette Fallon)

Curious facts: the cathedra – or lack of it

Although this building dates from the late 11th century, it didn’t become a cathedral until the early 12th, when the first Bishop of Ely was appointed in 1109. A cathedral is the place where a bishop has his cathedra, or chair, but the new bishop wasn’t given one, he just used the existing abbot’s seat. Today the diocese has two bishops and they use the two chairs on the south side of the presbytery that were made for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip for the Royal Maundy Serv...