![]()

This study is about one of the world's largest investment funds, the Trust Fund of the Social Security System of the United States. Hundreds of millions of people have made contributions to it over three quarters of a century. A very large number of the people who have paid into it have also received, or are receiving, retirement benefits, disability payments, or the proceeds from life insurance sent to their next of kin; all others who have made and are making contributions can expect these same types of benefits in the future.

As of December 21, 2010, the Social Security Trust Fund had assets of $2.609 trillion in the form of non-marketable Special Issue Government Bonds and no debts. Of this amount, total inflows to the Trust Fund in the form of payroll taxes exceed benefit payments and administrative expenses in the sum of $1.144 trillion. Consequently, the Trust fund's accumulation of earnings, in the form of interest income, over its first 74 years of existence, adds up to only $1.465 trillion. As of this writing, the Social Security Trust Fund has never invested a penny in stocks.

NEGATIVE EXCEPTIONALISM

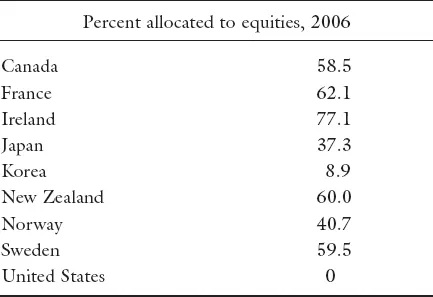

This is more than remarkable because many, if not most, nations do make stock investments in their public pension funds or social security programs. A recent study by Yermo (2008) covering eight OECD countries ( Canada, France, Ireland, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden) showed that in 2006 five of the eight kept more than half of their public pension reserve fund investments in equities, as shown in Table 1.1. In some countries, the reserve fund includes only a portion of all the public fund's assets. Canada diversified its social security investments from purely government bonds in 1998 and many countries did so much earlier. The Social Security Trust Fund, located in what is often viewed as the most capitalistic nation on earth, is clearly way behind the curve.

Table 1.1: Public Pension Reserve Funds in Eight OECD Countries — and the USA

Source: Yermo, J. (2008). Governance and Investment of Public Reserve Funds in Selected OECD Countries. OECD Working Papers on Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15, OECD Publishing, doi: 10.1787/244270553278.

While many have advocated investing a portion of Social Security funds in the stock market or privatizing Social Security in part or in full, these concepts have attained no serious traction. To illustrate how important stock investments are for the future of Social Security, and in boosting future US and global economic growth, this study will examine what would have happened if stocks had been included in the Social Security Trust Fund from its beginning in 1937.

In this vein, a central purpose of this book is to show that if the Social Security Trust Fund had pursued a simple, passive strategy of investments in marketable long-term government bonds and the stocks of large companies, its earnings and assets at the end of 2010, other things being equal, would have been $7.595 trillion larger. In other words, the Social Security Trust Fund would have ended 2010 as by far the world's largest investment fund with assets of $10.204 trillion, dwarfing the recently expanded Federal Reserve System's balance sheet by a factor of roughly four. This translates to about $32,900 per capita for the invested fund while the corresponding number for the existing Trust Fund is only somewhat more than $8,400. In 2010, the actual Trust Fund grew by only $69 billion while the invested fund, despite negative net inflows of $36.8 billion, would have grown by $1.18 trillion, or more than 17 times as much.

But other things would clearly not be equal. The increased demand for marketable bonds and stocks would in most years have resulted in a positive wealth effect. When people and economic agents feel wealthier, they become more willing to invest in financial, physical, intangible, and intellectual assets and property — and to spend more on consumption. This in turn results in a positive influence on government revenues. The combined effect of all these ingredients can only be what everyone seems to beg for — greater economic growth. In today's global markets, one nation's wealth effect spills across borders. Thus a Social Security Trust Fund invested in marketable Treasury bonds and a passive portfolio of global stocks would in the long term boost not only US but global economic growth — and reduce the need for government borrowing.

The above cannot avoid raising the obvious question. Where has the leadership of the American business community and the US government been in the last 75 years? Does it not believe in the stock market? Does it not appreciate the purchasing power that an efficient retirement plan, life insurance plan, and disability plan combination invested in bonds and stocks brings to the American people? The substantial long-run outperformance of stocks over bonds has been recognized for centuries.

To save and invest for retirement and in life insurance and disability insurance plans is to provide for a personal safety net. This can be accomplished via a multitude of avenues. People can save for retirement as individuals or via corporate or group plans or a national plan or some combination. Life insurance and disability insurance can be purchased individually or as a member of a group or of a national plan.

The central objective of companies or funds receiving retirement contributions or life insurance or disability insurance premiums is to invest their inflows to make them grow — and to do so in a compounding manner. This way, when the time for benefits arrives, the payments to the beneficiary will be many times larger than his or her inputs.

And how is this compounding growth of contributions achieved? Almost universally it is executed via investments in government and corporate bonds and in common and preferred stocks, with smaller allocations to alternative assets such as real estate, infrastructure, and commodities. Historically, investments have been in domestic securities but recently a trend towards diversification into global bonds and stocks has emerged. The point to be stressed then is that whether one looks at individuals' retirement plans, the pension funds of corporations, universities, foundations, and other not-for-profit entities, or the pension funds of local and state governments and its sub-entities, or, as we saw in Table 1.1, the public pension plans of modern nations, a portfolio of stocks and bonds is the principal asset held.

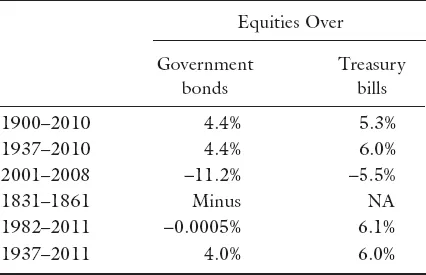

Investing Social Security funds in stocks strikes many people as risky and imprudent. Over short periods stocks can indeed be quite risky. If you look at the 18-year period 1992–2009 for example the S&P 500 total return stock index did indeed lose ground when compared to long-term US Treasury Bonds. This was also the case for the 30-year period October 1, 1981 through September 30, 2011, the first such 30-year period since 1831–1861 (Eddings and Applegate, 2011). To make the case for including stocks, it is necessary to look at long periods, such as the period spanning an individual's typical working life and retirement, over which stocks outperform bonds by several multiples. That is why this study examined the full 74-year period 1937 through 2010 — over which large company US stocks outperformed long-term US Treasury Bonds by a factor of 23.8 (Table 4.1).

The economic reason why stocks outperform bonds over long periods is due to what is generally referred to as the risk premium. Since stocks are typically riskier than bonds, investors will demand higher returns, on average, when they purchase stocks than when they acquire bonds, as compensation for their higher risk, fully realizing that the realized returns for stocks over short periods may well be lower.

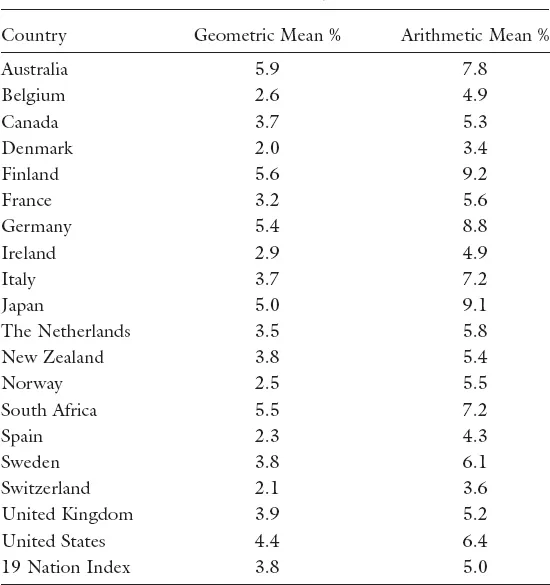

Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton (2002, 2011) calculated the realized risk premia of equities over long-term government bonds and over Treasury Bills for sixteen countries for the 101 years 1900–2000 and for nineteen nations for the 111 years 1900–2010. Over the 1900–2011 period, as Table 1.2 shows, the annualized realized geometric equity risk premium over long-term government bonds for the 19 Nation Index was 3.8%. Australia had the highest equity premium, 5.9%, and Denmark the lowest, 2.0%. The equity risk premium for the United States was 4.4% which is the same as the equity risk premium for the 74-year Social Security period 1937–2010. Siegel (2010) has documented the risk premia all the way back to 1801.

Table 1.2: Annualized Equity Risk Premia Relative to Long-Term Government Bonds for Nineteen Nations, 1900–2010

Source : Dimson, Elroy, Paul Marsh, and Mike Staunton (2011). “Equity Premia Around the World”. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/ abstract=1940165, October 21.

Table 1.3 shows the realized risk premia for US equities ( large company stocks) over both long-term government bonds and 30-day Treasury Bills for selected periods. As in Dimson, Marsh and Staunton (2002, 2011), an asset's risk premium is the return it earned measured as an investment in the other asset's principal and income combined. The 1982–2011 period was the first 30-year span since 1831–1861 that stocks underperformed bonds. The higher risk premia for Treasury Bills than for bonds is consistent with what is known as a generally rising term structure, the notion that longer maturities provide higher yields, or equivalently that there is a positive risk premium for bonds over bills.

Table 1.3: Realized Geometric Mean Risk Premia in the United States

Sources: Dimson, Elroy, Paul Marsh, and Mike Staunton (2011). Equity Premia Around the World. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1940165, October 21.

Morningstar, Inc., (2012). Ibbotson SBBI 2011 Classic Yearbook — Market Results for Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation 1926–2011, Chicago: Morningstar, Inc.

Eddings, Cordell and Evan Applegate (2011). Bonds Notch a Rare Win Over Stocks. Bloomberg Businessweek , November 7–November 13.

The 8-year period 2001–2008 is remarkable in that the realized risk premia for stocks were sharply negative versus both bonds and Treasury Bills.

THE RISK PREMIUM's SOURCE: NEAR-UNIVERSAL AVERSION TO RISK

Among individuals, risk aversion in financial matters is virtually universal, albeit in varying degrees, an observation which has been well documented empirically. Risk aversion also holds true for most economic entities. Institutions that are seen as too big to fail are the principal exception, as the recession that began in 2008 lucidly demonstrated.

The designers of the Security System did indeed have the wisdom of creating a Trust Fund in which the excess if inflows over benefit payments and administrative expenses would earn income. This income took the form of interest since all investments were in Special Issue Government Bonds. The crucial step of separating Social Security's financing from other governmental cash flows was thus established at the System's beginning. Unfortunately, this clear-cut separation became partially obscured in 1970 with the introduction of the Unified Budget concept.

The principal finding of this study is a simple reminder of the power of compounding over long time periods, say 60 years, roughly the beginning of a person's Social Security contributions to the end of that same person's receipts of Social Security benefits. Even small differences in average compound returns generate very large differences over an active life-time. The same is true for even modest differences in annual fees.

Chapter 2 gives a very brief overview of the Social Security System. Chapter 3 then looks at how Social Security constitutes the minimal safety net portion of an individual's personal safety net and provides a short summary of how Friedrich Hayek and Adam Smith see the minimal safety net. The System's principal shortcomings are then identified in Chapter 4, including how the Unified Budget concept has severely understated the US Government's financial deficits since 1970 by reducing the reported deficits by the surpluses of its various trust funds; this in turn has permitted roughly half of the growth in the federal debt owed to the public to grow under the cover of darkness… The monthly evolution of the Social Security Trust Fund is given in Chapter 5 under the assumption of a 50–50 starting division between passive investments in marketable long-term government bonds and large company stocks, with due respect given to transaction costs, market impact, mean reversion, the opportunity to invest in International stocks beginning in 1973, and the use of (roll-over) short-term borrowing when net inflows are negative. Various countries experience with privatized social security accounts are summarized in Chapter 6 along with how such accounts contribute to economic inefficiency, moral hazard, and productivity losses. Chapter 7 then argues that the Social Security System needs to be independent and professionally managed, much like the Federal Reserve System, with some concluding observations in the Epilogue.

![]()

Chapter

2 | SOCIAL SECURITY: A VERY BRIEF OVERVIEW |

The Social Security System of the United States, a child of the Great Depression, dates its birth to 1935. It was controversial then and has remained so in varying degrees ever since. The requirement since 1983 to make 75-year projections of its financial prospects, where demographic changes in the age distribution of the population play a key role, have generated sobering, and in some quarters nearly hysterical, reactions about its sustainability. It is not my intent to review these issues in any detail. Many careful studies of the problems facing Social Security have concluded that they can be solved by relatively minor adjustments. An especially cogent analysis in this vein is provided by Peter Diamond and Peter Orzag in their book Saving Social Security — A Balanced Approach (2004). Their adjustments to revenues and benefits are based on three components: improvements in life expectancy, changes in earnings inequality, and what they call the legacy debt that arose from the early recipients' relatively large benefits.

The theme of this inquiry is that the Social Security system currently in place, while generally comparing favorably to similar systems in other nations, has three serious flaws or shortcomings, each of which could be easily corrected. Payroll taxes are in essen...