![]()

page 1

Chapter 1

The Big Idea

On March 9, 1951, Edward Teller and Stan Ulam issued a report, LAMS 1225*, at the Los Alamos Scientific Lab† where they both worked at the time. It bore the ponderous, hardly illuminating title “On Heterocatalytic Detonation I. Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors,” and it changed everything. Since it dealt with thermonuclear weapons (H bombs), it was, of course, classified secret. For some reason, it remains secret to this day. The highly redacted version of it that can be found on the Web[1] is mostly white space. Nevertheless, most of what was in it is well known.

Their big idea, which we refer to now as radiation implosion, was that the electromagnetic radiation (largely X rays) emitted by a fission bomb, if appropriately channeled, could compress and heat a container of thermonuclear fuel sufficiently that that fuel would be ignited and the nuclear flame would propagate, not fizzle. The expected result: megatons of energy, not kilotons.‡ History validated the Teller-Ulam idea. (In the end, it was even more effective than they first imagined.) On exactly who contributed what to that big idea, history is a little fuzzier. More on that below. (Here and in what follows, I use “Teller-Ulam” not to anoint Teller as the senior author but only to keep the authors in alphabetical order, as they are on the report’s cover.)

page 2

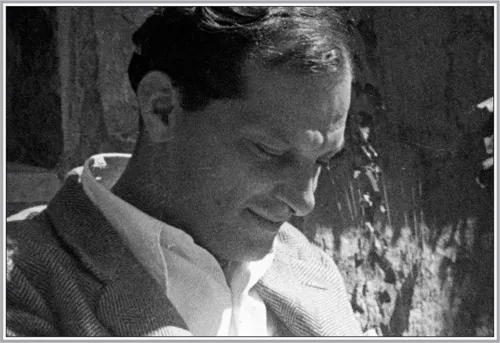

Stan Ulam, 1951. Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection.

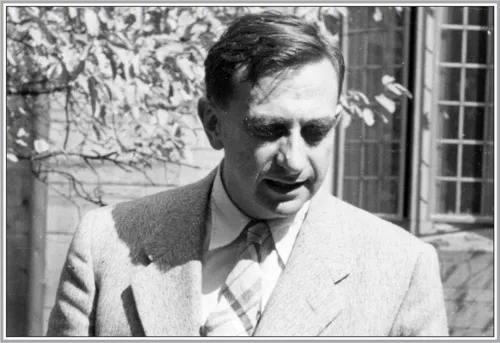

Stanislaw Ulam (always known as Stan) and Edward Teller (always Edward, never Ed) had some things in common. They were both émigrés from Eastern Europe—Stan from Poland, Edward from Hungary. They were both brilliant. They both had great curiosity about the physical world. And they were both a bit lazy. But oil and water also have some things in common. Stan and Edward differed more than they were alike. Stan, a mathematician with a gift for the practical as well as the abstract, was—to use current slang—laid-back. He had a droll sense of humor and a world-weary demeanor. He longed for the Polish coffee houses of his youth and the conversations and exchanges of ideas that took place in them. Edward was driven—driven by fervent anticommunism, by a desire to excel and be recognized—driven, it often seemed, by internal demons. Edward was too intense to show much sense of humor. Stan had an abundance of humor. Stan and Edward did not care very much for each other (which may help to explain why a “Heterocatalytic Detonation II” report never appeared).

page 3

Edward Teller, 1951. Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gift of Carlo Wick.

I was a twenty-four-year old junior physicist on the H-bomb design team at Los Alamos when the Teller-Ulam report was issued. I saw Stan and Edward every day. I liked them both, and continued to like them, and to interact with them now and then, for the rest of their lives. Stan and I later wrote a paper together, on using planets to help accelerate spacecraft (the so-called “slingshot effect”). Edward and I later worked together as consultants to aerospace companies in California.

page 4

Not everyone at the lab had equal affection for these two men. Carson Mark, the Canadian mathematician turned research administrator who headed the Theoretical Division during the H-bomb period, could scarcely abide Edward. He liked Stan, even if Stan didn’t care much for bureaucratic nice-ties and even if Stan sometimes wanted to chat when Carson wanted to work. John Wheeler, my mentor, although a straight-arrow quintessential American (he was born in Florida and raised in California, Ohio, and Maryland), was Edward’s soul mate. They were completely in tune in their anti-Communism and their fear of Soviet aggression. Balancing their pessimism about world affairs, they shared an optimism that nature would, in the end, abandon all resistance and yield her secrets if they just pressed hard enough. They had done some joint research together back in the 1930s (on the rotational properties of atomic nuclei) and their wives, Mici (MITT-cee) Teller and Janette Wheeler, were friends. It was Edward’s persuasion, in large part, that led Wheeler to interrupt a sabbatical in France and take a leave of absence from his academic duties at Princeton to spend the 1950-51 year at Los Alamos. Wheeler didn’t exactly dislike Stan, he just didn’t resonate with him. (There were, in fact, very few people whom Wheeler didn’t like, and he tried hard to mask whatever negative feelings he had toward those few.) For Wheeler’s taste, Stan was just a bit too laid-back, a bit too nonchalant.

Looking back, the odd thing to me now is that the Teller-Ulam idea, at the time it was advanced, didn’t shake the Earth under our feet. There were vibrations, but no earthquake. There was a new sense of cheer, but no parties or toasts or flag waving. We didn’t take the trouble to analyze, as so many have since, who exactly had what part of the idea and who deserves the greater credit. Years later, Edward said to me (I paraphrase), “Stan had a dozen ideas a day. They were almost all crazy. He himself had no idea which ones were valuable. It took me to pick out of the jumble the one good idea and exploit it.” Also years later, Stan said to me (again, I paraphrase), “Edward just couldn’t bring himself to admit, after his years of effort, that the idea on how to make the H bomb work was mine. He just had to take it and call it his own.”

page 5

The Teller-Ulam idea landed in the midst of numerous other ideas, of varying complexity and varying chance of succeeding. These included “boosting” (having a small container of thermonuclear fuel at the center of a fission bomb to “boost” the fission bomb’s yield); “Swiss cheese” (having numerous pockets of thermonuclear fuel scattered throughout fission fuel); the “alarm clock” (a name Edward Teller and Robert Richtmyer had coined in 1946 [2] [3] for alternating layers of fission and fusion fuel,* and which Andrei Sakharov in the Soviet Union, as we later learned, had separately envisioned and separately christened a “layer cake” in 1948[5]); and the “Yule log” (John Wheeler’s macabre name for a cylinder of thermonuclear fuel with no limit on its length or on its explosive power). Behind these lay the basic idea that had been around for nearly a decade and on which we were working assiduously at the time. That idea, known as the “Super” (and later as the “classical Super”) was simple in concept but maddeningly difficult to model mathematically, so that there was no sure sense of its potential. At the time of the Teller-Ulam idea, however, there were more reasons for pessimism than optimism about the prospects of the classical Super. Calculations† kept suggesting that igniting the fuel, even with a powerful fission bomb, and even with a good deal of highly “combustible” tritium mixed in, would not be easy, and that even if it were ignited, it would probably fizzle rather than propagate. A homeowner trying to get a fire started in a fireplace with wet logs and inadequate kindling can relate to the difficulty.

page 6

So the Teller-Ulam idea landed in our midst not as “just” another idea—it was special—but also not as a lone idea where there were none already. It was like a new sapling introduced into a nursery, not like a palm tree miraculously delivered into the desert. We thought, “Now there is an idea with merit,” and we started exploring its consequences at once—without immediately abandoning other ideas. As it turned out, the more we calculated, the more promising the new idea looked. Within three months, it had become the idea and was endorsed by the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission as the route to follow.

Up until February 1951, when Ulam approached Teller with an idea about imploding thermonuclear fuel and Teller realized (or, as he later claimed, recalled[6]) that radiation was the best thing to do the imploding, everyone working on H-bomb design in the United States assumed that the Super would have to be a “runaway” Super, a device in which the temperature of the material would have to “run away from” the temperature of the radiation. Otherwise, it seemed, the radiation would soak up too much of the energy and there wouldn’t be enough left to ignite the thermonuclear fuel and keep it burning. What could change this bleak prospect, Ulam and Teller realized, would be great compression of the material. It was this February meeting and its insight that led to the Teller-Ulam report of March 1951 and to the new direction in H-bomb design.

page 7

There were two insights that flowed from the Teller-Ulam discussion. The first was that thermal equilibrium—that is, having the matter and the radiation at the same temperature—could be tolerated if there was enough compression. Occupying less volume, the radiation would soak up less of the total energy. More energy would be left to heat the matter and stimulate its ignition and burning. Up until then, those of us working on the Super accepted the idea that thermal equilibrium would be intolerable because of the excessive “loss” of energy to radiation. And we accepted an argument Teller had made[7] that compression would not help. Teller had pointed out that although compressing the thermonuclear fuel increases its reaction rate, it also increases, and by the same factor, the rate at which the matter radiates away energy. So there was no net gain, he had argued, from compression. But that argument posits a runaway Super, which was our mindset at the time. Once equilibrium is established, matter is not “losing” energy to radiation, it is just exchanging energy with radiation, gaining as much as it is losing. If you jump into the North Atlantic, you lose energy because your temperature is higher than that of the water, and you will soon be drained of your energy. If instead you jump into a hot tub, energy flows equally back and forth between you and the water as you remain in equilibrium, and you can bask there all afternoon.

I have not found in the written record any sure evidence that Stan Ulam had in mind this insight about equilibrium when he came up with the idea that the thermonuclear fuel should be compressed. Nor do I remember him explicitly mentioning it at the time. Yet I have to assume that he did have it in mind. Otherwise there would have been no good reason to argue for compression. He had already done quite a lot of work on the runaway Super and knew its disconcerting inability to hang onto enough energy to keep a reaction going. He most likely knew, also, the Teller argument that for a runaway Super, compression would not help.

page 8

Teller, in the now-famous conversation with Ulam, apparently did realize very quickly, despite his earlier arguments to the contrary, that compression could be a key to success. In his memoirs, written many years later [8] (from which I quote in the next chapter), he says that Ulam’s idea was “far from original” and that, for the first time he [Teller] didn’t object to it.[9] He doesn’t tell us why he didn’t object, an odd omission given his previous rejection of the idea. In the same paragraph, in a further put-down, Teller says that Ulam did not actually understand why compression was a good idea.

Our understanding of this meeting is murky indeed despite the clarity of the conclusion that flowed from it. Did Ulam come in with a full understanding of why compression might be the key to success in designing an H bomb? We don’t know. Had Teller ever seriously entertained the idea of compression before? We don’t know. (In later writings, Teller claims to have had the idea before Christmas 1950 [10] and also about February 1, 1951.[11] These claims are dubious, especially in light of his own account of the meeting with Ulam,[12] and in light of my own recollection that no breakthrough idea occurred before late February 1951.) What we do know is that out of the meeting came the successful idea of the “equilibrium Super,” in which compression is so great that the huge amount of energy soaked up by radiation in equilibrium with matter is tolerable.

The second insight that came from the Ulam-Teller meeting was that radiation, at sufficiently high temperatu...