![]()

Section 1 —

Clinical Occupational Medicine

![]()

Chapter 1

Work and Health

David Koh∗ and Aw Tar Ching†

Occupational Health, Occupational and Environmental Medicine

The International Labor Office (ILO) and World Health Organization (WHO) define occupational health as ‘the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations.’ Occupational health service provision is a means to achieve this objective.

Occupational and environmental medicine, as defined by the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, is ‘the medical specialty devoted to the prevention and management of occupational and environmental injury, illness and disability, and promotion of health and productivity of workers, their families, and communities.’

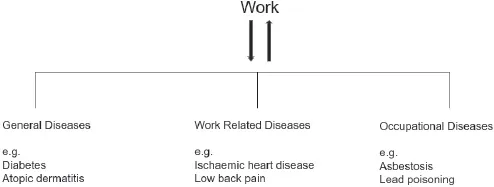

A crucial concept in occupational health is the recognition of a two-way relationship between work and health.

WORK HEALTH

Work may not only have an adverse impact on health, but it can also be beneficial to health and well-being. The health status of the worker will have an impact on work. The worker who is healthy is more likely to be productive than an unhealthy worker. Workers with impaired health are not only less productive but could also be a danger to themselves as well as other workers, the community and the environment. Hence the development of the ‘Total Worker Health’ concept recently proposed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (NIOSH, 2016).

Case Study 1

An oil company has known for years that the captain of one of its oil tankers had a serious drinking problem, but nonetheless left him in command of oil tankers. On one of the tanker journeys, the captain was drunk on duty and left an inexperienced officer in charge of navigating the tanker through hazardous icy conditions. The tanker ran aground on a reef and spilled millions of liters of crude oil, which coated thousands of kilometers of coastline and killed thousands of birds and marine mammals. Early detection of this captain’s drinking problem by an effective occupational health service could have prevented this incident.

History of Occupational Medicine

The discipline of occupational medicine is a relatively recent development in the history of modern medicine. In comparison to modern medicine which evolved from Hippocratic times over 2,500 years ago, occupational medicine only became a recognized discipline from the time of Ramazzini in the 18th century. Certain historical features in the development of occupational medicine have had a major impact on health and work.

First, its developmental direction was influenced by the fact that it was intimately linked to the legislative process, with legislation such as the Factories Act and Compensation Act in Great Britain, requiring greater consideration of measures to reduce injury and ill-health from workplace factors. Legislation remains an important component of occupational medicine practice today, and is a driver for change and implementation of preventive measures at workplaces.

During the Industrial Revolution from the mid-18th century, much attention was focused on workers in mines and factories, as these were situations where workers were at obvious health risk as a consequence of their work. This led to the discipline in the early days being known as Industrial Medicine or even Factory Medicine. With the recognition of other hazards in the workplace, however, the focus was enlarged to include all persons at work, and the term Occupational Medicine came into being.

The specialty has since evolved to be known as Occupational Health, for the reason that it is not only concerned with preventing disease but also promoting health among people who work. This also extended recognition to the contribution of non-medical professionals who made major contributions to health and safety in the workplace. The term occupational health recognizes the multidisciplinary nature of the specialty, as well as covers the provision of health services for working populations.

Work and Health

All workers may suffer from a spectrum of diseases, including (i) diseases that affect the general population that are not caused by occupational factors, although prevalent in the community; (ii) work-related diseases; and (iii) occupational diseases (Fig. 1).

Any physician or clinician seeing an individual patient must recognize the possible relationship between work and disease. Non-occupational diseases may be worsened by work activities or workplace exposures, or can occur mainly or solely because of workplace exposures. As an example of the former, many people who have diabetes mellitus may remain in the workforce. Their health condition could have an impact on work performance (as illustrated in Case Study 2) and equally, work may adversely affect the progression and/or prognosis of the diabetes.

Fig. 1. Categories of disease at the workplace.

Case Study 2

Mr. B is a factory supervisor who has to be placed on shiftwork after the restructuring of his company’s production and work processes. In addition, the recent acquisitions of new factories in overseas locations required him to travel abroad frequently.

Mr. B is an insulin-dependent diabetic and is concerned about his diabetic control in relation to the changes in the work situation. He rightly expresses concern about the diabetic control with regard to travel through several time zones, access to medical care in the developing countries where the new factories are located, and vaccination requirements for the travel. Familiarity with the requirements and schedules of the job will facilitate sound advice on diet and occupational health to Mr. B regarding his control of blood sugar.

Overt occupational diseases are often more commonly recognized in developing nations where the more hazardous occupations such as mining and traditional forms of agriculture are predominant, whereas work-related diseases generally become increasingly important as a country becomes more industrialized and phases out industries which are linked to an increased risk of the “traditional” occupational diseases. There is also a group of countries that underwent rapid economic growth in a short span of time, termed the newly industrializing countries (NICs). Such countries face a unique blend of traditional occupational diseases, emerging occupational diseases as well as work-related diseases.

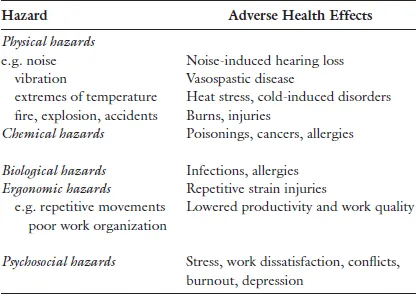

Occupational Diseases

Occupational diseases occur as a result of exposure to physical, chemical, biological or psychosocial factors in the workplace (Table 1).

These factors in the work environment are necessary in the causation of occupational diseases. For example, exposure to lead in the workplace is essential for lead poisoning, and exposure to silica is necessary for silicosis to occur. Other factors such as individual susceptibility may play a varying role in the development and progression of disease among exposed workers (i.e. workplace exposures are necessary but not necessarily sufficient as the sole cause of an occupational disease).

Occupational diseases occur exclusively among workers exposed to specific hazards (Figs. 2 and 3) and are cause specific. However, in some situations these diseases may also occur among the general community as a consequence of contamination of the environment from the workplace, or from secondary exposure through contaminated work clothes brought home to cause exposure among family members, e.g. asbestos, lead, and pesticides.

Table 1. Occupational Health Hazards and Adverse Health Effects

Fig. 2. A pregnant female laboratory technologist may be exposed to various chemicals (e.g. organic solvents) in her workplace.

Fig. 3. This worker who has to repeatedly lift cartons above shoulder height may develop neck and shoulder complaints.

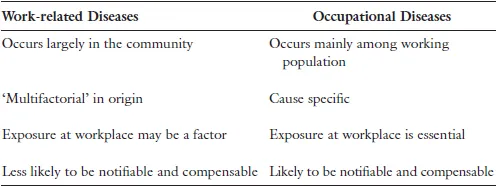

Table 2. Differences between Occupational and Work-related Diseases

Work-related Diseases

The WHO categorizes work-related diseases as ‘multifactorial’ in origin. These are diseases in which workplace factors may be associated in their occurrence but need not be a risk factor in each case, and are frequently seen in the general community. Such work-related diseases include (i) hypertension, (ii) ischemic heart disease, (iii) psychosomatic illness, (iv) musculoskeletal disorders, (v) chronic non-specific respiratory disease, and (vi) chronic bronchitis.

In these diseases, work may be associated in their causation or may aggravate a pre-existing condition. The main differences between occupational diseases and work-related diseases are shown in Table 2.

Clinical History Taking

It was only in 1700s that Bernadino Ramazzini (Fig. 4), physician and professor of medicine in Modena and Padua, Italy, recommended that physicians enquire about a patient’s occupation. Previous to this, the standard three questions recommended by Hippocrates were to enquire of the patient’s name, age and residence.

Fig. 4. Statue of Ramazzini at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Kitakyushu, Japan.

The routinely asked question “What is your job?” often provides inadequate information. It is important to obtain an adequate occupational history for the following reasons.

First, to assess the extent to which the illness has been caused or is related to the patient’s job. For example, the patient’s anemia may be consequent to exposure to lead, or the “malingering” patient may be in some way related to a highly stressful or hostile work environment.

Has Work Caused, or Is It in Some Way Associated with the Disease?

Another reason for taking a good occupational history is to assess the patient’s fitness to return to work. In this regard, the following four factors need to be considered:

(a)What are the long-term effects of the disease?

(b)What is the nature of the job the patient is returning to?

(c)Is the return to work likely to cause a recurrence of disease or is it likely to aggravate the disease? and

(d)Is returning to work likely to cause damage or ill-health to other work colleagues or the general community?

For instance, if the patient was seen for a condition which was clearly the result of occupational exposure, e.g. occupational asthma, occupational dermatitis, and musculoskeletal disorders due to poor ergonomic factors, then returning to the same work situation will only result in a recurrence of the condition. In this situation, corrective measures need to be taken at the workplace to prevent such recurrences.

There are other situations where return to some work may aggravate illness. For instance, a diabetic patient’s regular meal times and medication may be adversely affected if he returns to shift work, particularly as a diurnal variation exists with medication and insulin. Similarly, a patient after suffering from a myocardial infarction may not be able to return to work requiring heavy physical exertion or returning to a high-stress environment.

Return to work may also have an impact on work colleagues or the general community. For example, a patient with chronic infectious disease returning to work, such as a healthcare worker with hepatitis B or HIV may pose a risk to colleagues and patients. Another example is where the worker’s residual clinical condition may be a danger to himself and fellow workers, such as an epileptic (with poorly controlled seizures) working at a conveyor belt or at heights or alone at the worksite. Examples of ill-advised return to work affecting the public could be a worker with an infected wound on his finger returning to work as a food vendor, an airline pilot with psychological problems returning to fly, or the Case Study 3 below.

Case Study 3

Mr. C has just been discharged from the hospital after a cerebrovascular accident. He has responded well to treatment and has only a mild residual left-sided paresis. He decides to return to work as a taxi driver after a further two weeks of rest. This is not in contravention of any law, as there are no legislative requirements f...