![]()

CHAPTER1

Dragon Babies, There Are So Many of You

It was at the crack of dawn when the first jab of pain came. “Could this be it?” the first-time mum wondered, a quizzical look panning across her face. Her heart skipped a beat. Perhaps she had overeaten. After all, she did have a heavy dinner the evening before — hard-boiled egg with pork belly and toufu braised in dark soya sauce.

The contractions came again. This time, Moi was more certain. The bundle of joy that she and Hong had been looking forward to would soon be here. Both anxiety and joy flitted and danced in her heart.

Having a baby was a carefully planned affair. Their firstborn had to be a Dragon baby. After all, according to the Chinese zodiac, the year of the Dragon is especially fortunate for babies, marriages and businesses. Those born as Dragons are believed to be smart, lucky and magnanimous.

For this family in particular, having a Dragon baby was not only auspicious for the child but also for the father. According to the fortune teller at the wet market, a baby born the following year, which would be a Snake, wouldn’t get along well with Hong. Their personalities would qiong (meaning ‘clash’). If Moi didn’t have a baby that year, she would have to wait for another five years for a child to be compatible with Hong’s zodiac sign. That would be too long a wait.

[A]ccording to the Chinese zodiac, the year of the Dragon is especially fortunate for babies, marriages and businesses. Those born as Dragons are believed to be smart, lucky and magnanimous.

And the scan had shown it would be a boy. How propitious! The grandparents from both sides would be thrilled to have a Dragon grandson. Especially Hong’s parents. He would be the first grandchild for Ah Kong and Ah Mah (meaning ‘grandfather’ and ‘grandmother’ respectively).

Hong and Moi didn’t want to name their son Leng or Loong (meaning ‘dragon’). There would be many boys born that year called that. They wanted their son to be special and not one of many. Instead, they named him Teng (

meaning ‘to fly, rise, soaring like a dragon’ and suggestive of a bright future).

And so it was. Teng came into this world with feisty cries. Ah Mah said that meant Teng was ambitious.

Moi and Hong had become Ma and Pa.

Growing Up

Teng grew up feeling like a princeling. Not that the family was well to do. But being born in the year of the Dragon had, as one might expect, its benefits.

His father, a clerk, and his mother, a shop assistant at the hardware store near the market, doted on him — what he wanted was what he got. Nothing was too much for their precious Dragon son.

Ah Kong and Ah Mah showered gifts on him too and always gave him the benefit of the doubt whenever there were skirmishes between him and his siblings.

When it was time to register for a primary school, Ma and Pa found that getting into a good school was tougher than they had anticipated. Although they had read in the newspapers that there was a spike of some 8 percent in Dragon births compared to other years, they had misjudged the intensity of competition for school places. After all, the government did announce that to cater for the larger number of incoming Primary One students, they had opened additional new primary schools.

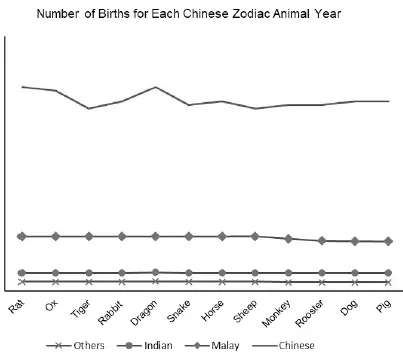

The newspapers had even writeups on the number of births in Singapore for each of the Chinese zodiac animal years and there was always a spike when it came to the year of the Dragon.

Teng went to a school within walking distance from his three-room HDB (Housing & Development Board) flat in Jurong. Not the best school in the neighbourhood, but the 200-metre distance meant that Teng could walk there on his own, not to mention the extra snooze he got compared to friends who lived farther away. And that short, leisurely walk stirred his interest in cars.

While the flats surrounding him seemed monotonously homogenous with no distinctive feature, the myriad of cars zooming by as Teng walked to school fascinated him, adding a spring to each of Teng’s steps.

Class sizes in his cohort were a little larger than usual to accommodate the Dragon babies. And more often than not, like Teng, his classmates were spoilt for choice by over-indulgent parents and grandparents.

Competition was stiff too. Teng had just mastered spelling and writing his full name in both English and Chinese. He thought it was an achievement, judging by the encouragement he received from Ah Mah, Ah Kong, Ma and Pa. But amongst his peers, it seemed to be anything but that.

During the first week of school, his form teacher was already reeling off her list of expectations — all homework must be handed in on time, multiplication tables must be memorised, each child was expected to read at least one English and one Chinese story book a week. The list went on.

To top it off, his form teacher would write on the side of the blackboard two sets of names — the names written in white chalk were the top three students who excelled in spelling; those written in red chalk were those who fared poorly. And with 45 students in the class, more than the usual size of 40, it was even harder to be in the top three.

Competition was everything. Some of his classmates were competitive on all fronts — they fought to be the first to raise their hand to answer a question; jostled to get the best seat when the teacher called the class to come forward during story time; and strived to be on the better team when it came to PE (Physical Education). They had their game face on at all times.

He remembered when Ma accompanied him to school to buy his textbooks. He didn’t understand why Ma wanted two sets of books. There was only one of him — why two books each for Chinese, English, Maths and even Music?

It turned out that many parents were kiasu (meaning ‘scared to lose’). They had bought two sets so that one could be kept in school, while the other was kept at home for self-study or for private tutors.

So even though they came from a humble background, Ma and Pa would spend less on themselves to make sure that Teng was not put at a disadvantage.

There were some 43,000 Dragon babies born that year and apparently, the textbook publisher had printed 50,000 copies, thinking it was more than enough. They had misjudged. Most of the parents were clamouring to buy more — the books were soon out of stock.

Teng had never felt such intense pressure before. After all, he had always been the favoured child and the thought that others were just as special as he was, was just quite discouraging.

The Cohort Size Effect

Once, Teng and his best friend Peter were comparing their largesse from Lunar New Year. They had amassed quite a large sum of money from their hong baos (meaning ‘red packets’).

“Teng, why study so hard?” lamented a naïve Peter in Singlish or Singapore’s English. “Born in the year of Dragon can give so much headache. So many Dragon babies. There’s so much competition.

I think just collecting hong bao is good enough. Aunties, uncles, grandfather, grandmother — they can give hong bao every year and we’re set for life.”

“Why are you complaining? Competition is good,” responded Teng.

“I thought so too. But that day, I saw someone on TV say something called the ‘kor-hot’ size effect or something like that. What a very cheem (meaning ‘difficult’) word,” said Peter, scratching his head. “Something like the more people there are in one age group, the harder it is to get a job or do well. And the man on TV said Dragon people suffer from this.”

“Hah? Got like that one meh?” exclaimed Teng, as he sat up straight on hearing this.

He had always been told by Ah Mah that as a Dragon baby, he would always be blessed with good fortune, and that life would be smooth sailing. So what is this about not doing well?

Teng never had problems with money. What he wanted, his parents provided, especially since he had been diagnosed with asthma. On the days the air got a little bit hazy, Teng would be wheezing away with an itchy nose. But the doctor had reassured Ma that he would probably outgrow his asthma.

Once, he had gone to a scouts’ campfire event at a school in the Bukit Timah area. He drooled as he saw the fleet of polished Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs waiting to pick up the kids. Wouldn’t it be nice to be chauffeured around in a spanking new set of wheels and show it off to his friends?

Another time, after Ah Mah had bought his favourite Van Houten almond chocolates, he had proudly boasted to her, “Ah Mah, next time when I grow up, I will become my own boss. Then, I will blanjah (meaning ‘treat’) you to the best restaurant in Singapore.”

Yes, Teng had dreams of making it big.

Now this ‘kor-hot’ size effect may well dash his big dreams. Where is the good fortune he was supposed to have? Teng was puzzled and troubled.

“Let’s go ask Miss Aishah. Maybe she knows what ‘kor-hot’ means,” he suggested to Peter.

Miss Aishah Explains

Miss Aishah was their English teacher. And their favourite too. Not only was she pretty, she was also young — unlike the old draconian Science teacher the boys had.

Pleasantly surprised at the two rambunctious boys’ question, she explained, “Ah . . . I know what you mean, Peter. That was the study reported on Channel 5 News the other evening.

“Spelt C-O-H-O-R-T, ‘cohort’ means the group of people similar to you — for example in age. So you can say that people born in the year of the Dragon, like you, belong to the same cohort.”

“So that means we have a big cohort lah, since got so many of us Dragon babies?” interrupted Peter eagerly. He tried to speak in better English but the truth of the matter was everyone in his family and almost all the students in school spoke Singlish.

“Yes, the Dragon year babies belong to a larger cohort than, say, those born in the year of the Tiger, which usually see fewer births,” explained Miss Aishah.

“But why big cohort means we suffer?” interjected Teng anxiously.

Getting a little annoyed at the frequent interruption, Miss Aishah sat both boys down and explained to them what she had heard over the TV News and read in the newspapers.

“Research has shown that as cohort size increases, there is lower productivity and wages. Unemployment is also higher. People from larger cohorts are also more likely to commit crime. They tend to form higher material aspirations during childhood. But because opportunities are limited, there is a gap between aspiration and reality. Does this make sense to you?”

[A]s cohort size increases, there is lower productivity and wages. Unemployment is also higher. People from larger cohorts are also more likely to commit crime. They tend to form higher material aspirations during childhood.

“You mean we have big dreams. And being Dragon babies, even bigger dreams. But because there are so many of us, and opportunities are fewer, more will be disappointed?” Teng asked, trying to put what Miss Aishah had said in the kind of English he understood.

“Yes, you’ve gotten it right,” smiled Miss Aishah. She continued, “That news report was from a study done by a group of professors from the National University of Singapore (NUS). They studied people born in the year of Dragon as well as those born in other years.

“They found that the number of Chinese births is 8.4 percent higher in Dragon years and 7.3 percent lower in Tiger years. You know why, right? Chinese parents like their children to be born in the year of the Dragon because it means good luck, while babies born in the year of the Tiger, especially females, may be too fierce. So they want babies in the Dragon year but not in the Tiger year.

“That is why when schools are admitting children born in the Dragon year, we have to open more classes to cater for the larger intake.

“Do you want to know more about what the professors found?” asked Miss Aishah.

The boys nodded their heads eagerly.

Education and Salary

Miss Aishah continued, “The professors were very detailed in their research. They collected data from people entering the local universities, as well as birth, financial and property data from different sources. They also searched bankruptcy records.

“They were also mindful that Singaporean men had to do National Service and enter the university two years after girls born in the same year.

“After accounting for this, the profs found that as a cohort, people born in the year of the Dragon had lower admission scores than people born in other years. This means they are about 3 percent less likely to be admitted to the university than people born in other years.”

“But why? We are supposed to be smart and lucky,” fumed an upset Peter, agitated at this bad news.

“Well,” explained Miss Aishah, “the professors explained that there are at least two possible reasons. The first is what they call selection effects. This means that perhaps families from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, with poorer financial management skills, are more likely to practise zodiac birth timing. And such family circumstances might put their Dragon babies at a disadvantage. But the NUS professors found little evidence of this.”

“Oh! Then what is the reaso...