![]()

1

Signs of the Times

People were always on the watch for “signs” which, according to the prophetic tradition, were to herald and accompany the final “time of troubles”; and since the “signs” included bad rulers, civil discord, war, drought, famine, plague, comets, sudden deaths of prominent persons and an increase in general sinfulness, there was never any difficulty about finding them.

—Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium

There would be no search for the meaning of history if its meaning were manifest in historical events. It is the very absence of meaning in the events themselves that motivates the quest.

—Karl Löwitth, Meaning in History

UNDERSTANDING HOW a set of stories told by three small shepherds from a rural village so greatly affected modern Portuguese history involves tacking back and forth between micro- and macrolevel processes, between individual and collective visions, between inherited pasts and hoped-for futures. It also entails recognizing that the apparition drama was surrounded by a range of related dramas and personae that both shaped and were shaped by it. In this chapter, I discuss some fragments of Portuguese history that communicate something about the affective climate and field of social concerns that characterized the opening decades of the Portuguese twentieth century. The full relevance of the vignettes that follow may not be immediately apparent, but some of the characteristics that link them will, I hope, suggest themselves in advance of a more complete analysis.

The Good Doctor

On August 18, 1897, Dr. Sousa Martins, Portugal's best-known and most beloved physician, died of pulmonary tuberculosis. Sousa Martins was an internationally recognized expert on tuberculosis and nervous disorders who spent the bulk of his professional career battling disease in Lisbon's working-class ghettos. The population of Lisbon had more than doubled during the nineteenth century. One of the many consequences of rapid urban immigration was a public health crisis. Impoverished rural residents who migrated to the city frequently found themselves living in overcrowded slums with inadequate sanitation. There they were particularly susceptible to diseases such as pellagra, typhus, viral gastroenteritis, measles, and tuberculosis. Worse still, those most at risk were often the least capable of securing professional medical help, especially during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, when relations between labor and management in Portugal's urban centers became increasing hostile and food and lodging prices climbed beyond the reach of the urban underclass. Sousa Martins chose to become a physician in this rapidly changing social and epidemiological climate, and his commitment to serving those most in need, regardless of whether they could afford to pay, earned him a reputation as a folk saint as early as 1881 (Machado Pais 1994, 58). Even those who eventually protested the linkage of the “great man of science” with folk religious beliefs acknowledged that Dr. Sousa Martins was a friend to the poor who made great personal sacrifices to improve the lives of others.

In death, Sousa Martins became an object of cult devotion several times over. Some revered him as a miracle worker, magician, and martyr of sorts. Within a decade after his death, scores of pilgrims were petitioning the doctor to intervene on behalf of ill friends and relatives, and lapidaries and other ex-votos were being deposited at the foot of the statue constructed in his honor at do Campo dos Mártires in Lisbon and at his mausoleum in the cemetery at Alhandra. In the imaginations of at least some of the poor and mostly illiterate patients Dr. Sousa Martins had touched in life, he had become a “saint” or “spiritual guide” who specialized in killing microbes and safeguarding patients during surgeries.

Dr. Sousa Martins's professional colleagues and admirers, however, refused to recognize anything supernatural in the doctor's being or exploits. Many of these men were affiliated with the Republican Party and were intellectuals committed to the promotion of scientific knowledge and the creation of a more modern, rational society. Still, this group was no less interested than Dr. Sousa Martins's patients in forging a cultlike devotion to their departed friend and everything they believed his life had stood for.

By and large, members of the political and scientific intelligentsia revered Dr. Sousa Martins as a medical researcher who had served Portuguese society as a progressive political activist and reformer, and they were right to do so. A self-declared “Jacobin of medicine,” Sousa Martins had fought for the standardization and regulation of pharmaceuticals in Portugal during an era when homemade and even some mass-produced remedies caused public harm. He had attempted to improve sanitation in some of the poorest areas in the city and had supported numerous public works projects designed to improve the lives of the Lisbon masses. Additionally, he was the author of medical textbooks and a professor at the city's medical school. He was one of Portugal's few internationally recognized scientists. He was also an ardent patriot and a pseudosociologist who conceived of society as a superorganism whose inner workings needed to be rigorously studied and better understood. This ultimately led to his being celebrated as a modern, secular, and democratic role model by Republican activists at the turn of the twentieth century.

In his analysis of the two very different ways Sousa Martins has been remembered over time, Machado Pais contends that “these two different forms of consecration are themselves associated with two distinct processes of social recreation around Sousa Martins; two distinct imaginary universes centered on the same man; two distinct forms of belief” (1994, 13). Machado Pais's claim is correct, and he has done a fine job documenting the ways followers from the two camps created and maintained distinct hagiographies for the good doctor—a phenomenon I observed firsthand in 1997 during the centenary celebration of Sousa Martins's death. However, I want to go a bit further and suggest that the ongoing struggle over the memory of Dr. Sousa Martins bears a close family resemblance to other schisms and conflicts of vision that plagued Portuguese national society at the turn of the twentieth century.

Beyond this, the case of Dr. Sousa Martins is instructive in that it shows how ordinary Portuguese people defied institutional pressures to create meaning or value on their own terms during this period. The Catholic Church, like the self-consciously modern reformers just mentioned, resolutely refused to recognize Dr. Sousa Martins as a saint after his death in 1897. However, this did not deter some devout Catholics from “beatifying” the doctor and developing votive relationships with him. This situation is reflective of the acute breakdown of institutional authority that began in 1890 and the urgent need to update conventional strategies for coping with various forms of crisis during the difficult period that followed. After all, saints are intermediaries who petition for and deliver God's grace on behalf of the suffering. New saints, especially those not sanctioned by the Church, are often recognized by the laity as being worthy of devotion because of their apparent ability to invoke power and influence outcomes where and when more conventional measures have failed. Dr. Sousa Martins was recognized as such an individual by people who were only loosely bound to the orthodoxy of a Church that had been unable to effectively administer to the needs of the rapidly expanding urban population as the turn of the twentieth century came and went. However, it is clear that increased distance from the Church and regular clergy did not amount to a nullification of religious sentiment, even for those with anticlerical leanings. Rather, for many people a set of folk Catholic traditions continued to mediate the assimilation of new, urban, and increasingly secular influences. Thus, during the opening decades of the twentieth century, in Portugal, a modern scientist and his black bag would be incorporated into popular religious systems and be reconfigured as holy things. His works would be looked upon as bridging divine and human domains, guaranteeing God's presence in a rapidly changing world. New social and symbolic relations would be organized around his fabled attempts to ameliorate suffering, and these realities would be created and affirmed by common people without the support of dominant political or religious institutions.

Back to the Future

The Portuguese historian Rui Ramos has noted that in 1880, when the three hundredth anniversary of the death of the epic poet Luis de Camões was celebrated, there were only four public statues in the city of Lisbon, three of which were less than fifteen years old (Mattoso and Ramos 1994, 69). Within just a few decades, however, the city had been radically transformed; it was dotted with monuments celebrating the Portuguese past. Public commemorations of deceased Portuguese culture heroes that included speeches, parades and processions had become commonplace. According to Ramos, this rather rapid transformation coincided with a groundswell of patriotic fervor that reached a zenith in 1890, when the Portuguese plan to create a “rose-colored map” of Africa was foiled by Great Britain and Belgium. However, at this historical juncture, reconnecting with glorious figures and moments from the past was about more than an attempt to forge a coherent national identity in the run-up to the Great War, although this was part of what was at stake. Resurrecting long-dead heroes and creating new bridges between the distant past and the rapidly changing present were part of a larger, collective attempt to cope with an emerging identity crisis. As Cornelius Castoriadis has noted, to survive in a world with its own ways and reasons for being, every society must continue to produce answers to a few fundamental questions: Who are we as a collectivity? What are we for one another? Where and in what are we? What do we want, what do we desire, what are we lacking? (Castoriadis 1998, 147). In the Portuguese case, the commemorations represented attempts to act out much-needed answers to those questions. They were rituals of collective renarration designed to lend a sense of coherence, plausibility, and permanence to the stories Portuguese people wanted to tell themselves about themselves.

Portugal's great seafaring and colonial legacy figured most prominently in the large-scale historical commemorations that were organized during the 1880s and 1890s. In 1880, the three hundredth anniversary of Camões's death was celebrated for three days to promote a “national revival.” This was followed by commemorations marking the four hundredth anniversary of Vasco da Gama's opening of the sea route to India in 1889, and the five hundredth anniversary of the birth of Henry the Navigator in 1894.

By the late nineteenth century, poets, playwrights, and novelists had become international celebrities all over Europe. The epic poet Camões, whose works had been translated into English, was already Portugal's most celebrated author. By 1880, when his commemoration took place, his work served as a testament to the fact that Portugal was, in fact, a “civilized” country with a rich artistic heritage—a country on par with the other great European powers. Henry the Navigator (Infante Henrique) was viewed as the architect of Portugal's Golden Age. He had been responsible for fielding a fleet of capable mariners during the fifteenth century who established trade relations with peoples on both coasts of Africa, eventually sailing to territories as far away as Brazil, India, Japan, and the Indonesian archipelago. Accurately or not, he was remembered as a brilliant cartographer and patron of exploration who helped change the shape of the known world. Vasco da Gama, whom Camões also mythologized in Os Lusiadas,1 had long been configured by the Portuguese as the country's paradigmatic sea-hero and explorer. However, by the end of the nineteenth century he had also come to represent the larger legacy of discovery and imperial expansion that had once made Portugal a great power, and that many hoped would restore its greatness.

Restoration, or resurgence, was an important theme at the time because by the end of the nineteenth century it had become painfully clear that Portugal, once Europe's wealthiest and most expansive empire, had become politically and economically, as well as geographically, peripheral. The country was still struggling to recover from the destructive first half of the nineteenth century,2 and it lacked both the infrastructure and the industry to compete with its more economically developed European neighbors. To remedy this situation, in 1851 the reformed Portuguese government, controlled by members of the two dominant political parties, the “Historicals” and the “Regenerators,” had undertaken a series of massive public works projects designed to modernize the country and ready its population to enter the new century. However, this project was derailed by scandal and economic convulsions beyond the government's control (see Schwartzman 1989). As a result, by the 1880s, when the commemorations in question were being organized, Portugal was once again in search of ways to modernize, grow, and compete with its European neighbors. This in turn gave rise to the dream of reviving the empire by returning to the endeavor that had initially made it great— colonialism. There were clearly nationalist ambitions at stake in the plan to seize control of the Zambezi basin and connect Angola and Mozambique. As Oliveira Marques notes, “the Portuguese were always comparing their country with the most progressive and the wealthiest nations of the world,” and many of those nations also had their eyes on Africa (Marques 1976, 140). It was, therefore, no accident that between 1880 and 1894 the Portuguese chose to commemorate the Age of Discovery. The country seemed to be self-consciously headed back to the future, and the mythical celebration of the origins of empire was an important part of this process.

However, the heroes of the Age of Discovery were not the only figures to be publicly resurrected and re-presented to a late nineteenth-century audience unsure of the past and anxious about the future. In 1882, the newly formed Republican Party used the bicentennial celebration of the death of the Marquis de Pombal (1699-1782) to help define itself.

Pombal had been appointed chief minister in the wake of the terrible Lisbon earthquake in 1755. He became famous for rebuilding the devastated center of the capital city on a rational, geometric grid plan that even today provides a profound contrast to the mazelike medieval sectors of the city that surround it. However, in many ways this reconstruction project served as a spatial metaphor for his introduction of a much broader set of Enlightenment ideals into Portuguese society—ideals that divided the country in lasting ways. In addition to supporting the creation of a fledgling merchant class, Pombal expelled the Jesuit order, dismantled the Inquisition as a separate tribunal, and drastically limited the power of the feudal nobility. It was this legacy, along with Pombal's strong commitment to the importation of foreign cultural, political, and economic models, that the Republican Party identified with when it utilized Pombal's commemoration as a platform for critiquing the constitutional monarchy and promoting its liberal agenda.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese Church was also busy resurrecting one of its long-dead heroes, Nuno Alvares Pereira (1360-1431), sometimes referred to as the “Constable of Portugal” or the “Protector of the Kingdom” (Condestável do Reino), a title he earned in 1384 when John of Aviz effectively made him the commander of the Portuguese military. Nuno is probably best known as the hero of the Portuguese victory at the battle of Aljubarotta in 1388, which Pope Boniface IX (1356-1404) declared a holy miracle in a papal bull in 1391. Nuno Alvares Pereira, who believed that the Virgin Mary had assisted him in battle in exchange for his devotion, went on to build six churches in her honor before taking his vows as a monk under the name Nuno de Santa Maria at the Carmelite Convent in Lisbon.3

John Haffert has claimed that “by 1870, the popularity of Nuno had suddenly become so great again that the Most Reverend Angelus Savini, Vicar-General of the Carmelites, wrote to a Portuguese priest of his Order and told him to prepare all the documents necessary for the approbation of Nuno's cult” (Haffert 1945, 183). Soon thereafter a number of scholarly biographies of Nuno's life appeared, including J. P. Oliveira's The Life of Nun'Alvares, published in 1884. This book, like Renan's Life of Jesus, treated Nuno as an exemplary human being rather than a preordained servant of God, and by doing so it popularized Nuno with an entire generation of both pious and impious Portuguese. In 1909 the cardinal patriarch of Lisbon authorized public veneration of Nuno in the patriarchal see, which resulted in the rapid formation of his cult (ibid., 184). In 1918, Nuno Alvares Pereira was finally beatified by Pope Benedict XV, and two years later the Republican government passed a law making August 14 a national holiday—a celebration of patriotism (Festa do Patriotismo) honoring the memory of Blessed Nuno, who Bernardino Machado said “was one of great patriots of our land” (Castro Leal 1999, 79).4

Although the list is incomplete, it is clear that at the end of the nineteenth century, the poet, the explorer, the rebuilder, and the protector were all resurrected to suggest something to the public about what it meant to be Portuguese. However, these heroic figures were also brought back to life to combat an emerging sense that the world they had helped to create was moving toward extinction. Thus, the time-binding rituals organized around these figures and their deeds were, in many ways, disguised attempts to recover a sense of unity, pride, and security that had largely gone missing.

Postcards, Pestilence, and Politics

Both photographic and cartoon postcards were printed and sold in abundance in Lisbon around the turn of the twentieth century. The cards were produced by small publishing companies and sold along with newspapers and magazines in Lisbon's abundant tobacco shops and kiosks. Early on, portraits and photographs of the past and present monarchs of Portugal and scenes of city life dominated Portuguese postcard imagery. However, cartooned cards enjoyed an explosive popularity during the first decade of the twentieth century as competing political groups employed them as a means to advance their propaganda.

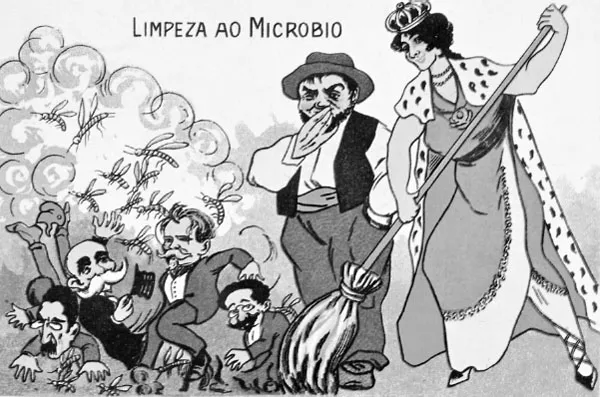

The card shown here was reprinted and distributed as part of a collection released by the Museum and Library of the Republic and Resistance in Lisbon Portugal in 1997. Unfortunately, neither the original illustrator nor the publishers were identified by the collection curators. However, it is known that the card appeared in Lisbon in 1906, the same year that the king of Portugal, Dom Carlos I, appointed the conservative politician João Franco premier, and the card expresses the significance of this event in a somewhat obscure but telling way.

The card depicts a female figure in royal garb sweeping away a prominent cast of republican politicians and activists, the “Microbio”—germs— of the postcard's caption, as a recurrent character in the political postcards of the day known as “Zé Povinho,” the Portuguese Everyman, looks on. The monarchical figure5 likely represents Queen Amelia of Portugal, although it is not immediately clear why she rather than João Franco or the king of Portugal has been portrayed as the agent behind the political extirpation represented in the cartoon. This depiction is emblematic of Republican Party propaganda during this period, which emphasized the queen mother's close ties to her Jesuit handlers and the Catholic Nationalist Party (Robinson 1977). The underlying message of the card seems to be that the queen mother, who was a very devout woman, exerted pressure on her husband to defend the interests of the Catholic Right in Portugal, which led to Franco's appointment and subsequent crackdown on Republican activists. This involved more than five hundred arrests, a total censorship of the press, and the dismissal of the Portuguese parliament to prevent legislators from obstructing his proverbial house cleaning. Thus, the card suggests that the queen and the religious orders rather than King Carlos I were the true executors of state power.

“The Cleansing” (1906). ( Reprinted with...