![]()

1 Fantasy

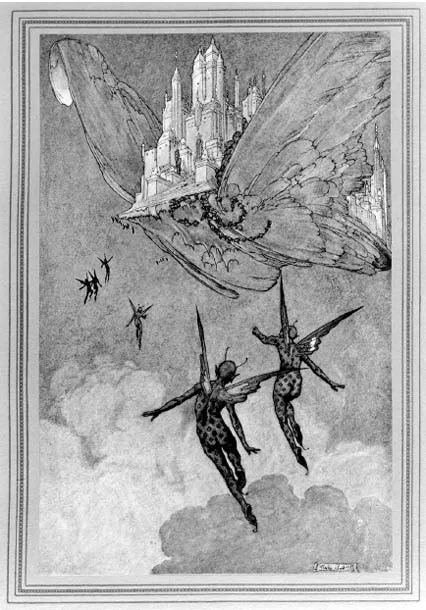

Nineteenth-century fantasy illustration often focused on flight that gave transformed humans the aerial view of raptors.

FANTASY OPENS ON FAERIE. BRITONS LONG IMAGined faerie as the place of enchantment, sorcery, and illusion, the ground itself of visual magic, of glamour. Well into the eighteenth century, rural Britons knew it sometimes as a place and sometimes as pure illusion itself.1 Early nineteenth-century novelists reshaped rural tradition into the foundation of contemporary fantasy fiction; always they emphasized the visual portal between the mundane world and faerie.

In Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre, her protagonist tells Rochester that the men in green forsook England a hundred years before she encountered him in Hay Lane one moonlit night, and that no longer will summer, harvest, or winter moon shine on their revels. Unnerved by “fairy tales” and injured from his fall on the ice-covered lane, Rochester remains unconvinced, and wonders if Jane Eyre is not of faerie herself.2 Thirteen years earlier, Walter Scott assured readers of his Demonology and Witchcraft that some noble families traced their ancestry back to the goblins and nymphs still emblazoned on coats of arms.3 Rural, traditional faerie of the sort Jane Eyre alludes to no more embraces the fairies who trick Shakespeare’s Falstaff than it does the elfin or insect-winged creatures of late-Victorian and Edwardian children’s book illustration. Faerie is precisely what Tolkien called it, the perilous realm.4 Just off the woods or moorland path, especially after dark, faerie is another realm altogether and its ruler is the visual.5 Nowadays fantasy fiction offers the most popular portal opening into it, but glamour photography offers another, one intimately connected with Brontëan glamour.

In college I first glimpsed some tracery connecting Edmund Spenser’s late sixteenth-century The Faerie Queen and The Vision of Piers Plowman with my own glamour photography avocation. In a blaze of light a thousand times the brilliance of the sun, the nature goddess emerges from the woods near the end of The Faerie Queen: Spenser likens her splendor, even the bright and wondrous shining of her attire, to an image seen in a glass or mirror.6 “For thy it round and hollow shaped was,/Like to the world it self, and seem’d a world of glas,” Spenser says of Merlin’s wondrous looking glass in which Britomart scrys afar.7 Britomart is not the wizard, only a first-time scryer, but she uses the glass acutely, and her momentary control intrigued me, the photographer fancying himself in control of planes and arcs of glass.

Other glass made me wonder about the Spenserian vision.8 Colonial-era windowpanes sometimes vary in thickness: the waviness warps seeing.9 Along the Massachusetts coast, centuries-old panes made on Cape Cod now turn yellowish or lavender. At dawn or evening, often when snow covers the ground and the sky is clear, the tints skew ordinary seeing in ways that struck me as peculiarly if elusively evoked in The Faerie Queen.10 Spenser concerned himself with faerie, illusion, and glamour, with what Tolkien calls “sub-creation,” the making of visions beautiful and terrible. Glamour photography seemed a sub-creation akin to the view through the wavy, lavender glass in my old house surrounded by fields.11 Shoved against oblivion by microchips and pixels, this old way of looking at the world along with glass and film cameras, film, paper, and darkrooms now strike almost everyone as obsolete.12 But something lingers in the farewell glimmer.

This book examines those who are not “almost everyone.”13 Such individuals remain sensitive to the glamour implicit in faerie and in traditional photographic image making, see that glamour gaining power unnoticed, and value the images sometimes produced in image making now and then skewed by technical accident.14 Some image makers possess a sort of second sight, and sometimes a film camera records gleams of the vitreous Spenserian world.15

Technique and equipment facilitate accident. In 1953 Franke & Heidecke introduced a graduated filter designed only for black-and-white photography. In distancing the filter from the lens, it makes the Rolleiflex camera even more versatile by acting upon direct and reflected sunlight before the rays reach the vicinity of the lens itself. A glass rectangle, one half dyed yellow, slides up and down through a square frame that fits onto the lens hood. With the Rolleiflex mounted on a tripod, the photographer slips the unit onto the finding lens, moves the yellow area of the glass until its lower edge aligns with the horizon, locks the set screw, then shifts the filter to the taking lens. The yellow zone accentuates clouds but enables full exposure of the landscape below. Given the great sensitivity of orthochromatic film to the blue-violet end of the spectrum, the gradient filter holds back the intense blue of mountain skies while enabling greater (and more precise) exposure of landscape browns and greens. With panchromatic film, the photographer reverses the position of the yellow zone, especially in springtime when high-altitude landscapes are light green against deep blue skies.16 Most Rolleiflex owners contented themselves with one of several ordinary yellow filters, but the expensive Verlauf filter still makes possible the extremely nuanced landscape work implicit in the meaning of its name: it scatters light over time and distance.17 It enables Rolleiflex users to record differences of light above and below horizon lines, and to experiment with optical effects unknown to photographers who simply screw circular filters immediately in front of lenses.18 It makes the Rolleiflex to which it is attached even more likely to well-nigh accidentally record something through glass.19

Despite the best efforts of photographic equipment manufacturers, art school instructors, and above all, mainstream critics of photography-as-art, throughout the twentieth century a minority of photographers savored the risky magic implicit in glamour- or fantasy-based image making.20 Almost never noticed by critics except when scorned or condemned, their efforts skirt the boundaries of propriety, pornography, and the aesthetic and moral standards espoused by corporate visual media, especially those producing images under government license.21 Minority-created images evolve from opposition to establishment standards and find scant place in histories of art, photographic illustration, advertising, even amateur image-making manuals.22 As traditional photography now seems time-consuming, risky, and expensive to people who want to see their electronic images instantly, otherwise self-effacing people, particularly young people condemned by their peers as traditionalist or nerdy, find fantasy fiction addressing issues that fascinate some photographers.23

Most fantasy fiction is trash. Shopping-mall bookstores retail it by the yard, and anyone who delves into it almost always discovers formulaic, awkward prose battered by science-fiction competition. Badly written and worse edited, the bulk of it builds on the late-1950s popularity of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings or older work by Lord Dunsany and H. P. Lovecraft. Castles, ruins, thatched-roof villages, greenways, and windblown seaports materialize in vaguely medieval settings; goblins, dwarfs, trolls, orcs, elves, and humans converge in plots featuring quests, coming-of-age tribulations, erroneous succession to thrones, and, frequently, large dragons guarding treasure. Protagonists often leave humdrum real-world lives by accident: they find the woods out back, the disused commuter train station, the overgrown cart path, the abandoned gas station, the thicket behind the playground as gateways to the perilous realm.24

Place-names, old roads, temples, barrows, standing stones, and assorted other landscape constituents figure largely in Tolkien’s fantasy writing but also in his scholarly work because they help archaic words and concepts endure.25 The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings introduce even young readers to the significance of words, especially those applied to place. “Real names tell you the story of the things they belong to in my language, in the Old Entish as you might say,” Treebeard insists to the Hobbits; he then speaks in his own tongue before asking their pardon. “That is part of my name for it; I do not know what the word is in the outside languages.”26 Once noticed, often by adults rereading the books, Tolkien’s philological didacticism intrigues not least because it typically parallels acute scrutiny of the visual environment.27

Tolkien’s finely developed visual capabilities manifested themselves in his watercolors and the maps he made for his books, but his lifelong commitment to archaic northern language explains his fascination with concepts ranging from how twisting produces both wreaths and wraiths to glimpses of things seen in shadowed woods.28 The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings describe landscape topographically from a pedestrian viewpoint: in many ways, both books work as travel narratives and adventures alike.29 Roads and paths preoccupied Tolkien, who continuously wondered at perceptions of them; the ways Hobbits and others discern paths at twilight or in different seasons of the year order much of the plots.30 One daybreak in October, the Hobbits and Strider discern a military-made path in the foothills of mountains: “It ran cunningly, taking a line that seemed chosen so as to keep as much hidden as possible from view, both of the hilltops above and of the flats to the west.” Strider the ranger eventually explains the reason for the path leading to Amon Sûl, the hill called Weathertop in Common Speech where Elendil watched for Gil-galad returning from Faerie in the West.31 But the path, archaic place-name, and local history in time lead, not only to misadventure away from easily discerned paths and old roads and other greenways long untrodden by long-distance wayfarers and even paths scarcely descried from hilltops at noonday, but to another way of seeing altogether.32

Glimpses open on glamour, especially in dim light, and words often corroborate what the sensitive see, perhaps particularly those sensitives free of advertising-industry goggles and able to descry auras.33

In the late 1960s and early 1970s a handful of writers moved along a slender gray path away from Tolkien’s emphasis on philology toward more than fleeting glimpses of glamour. Susan Cooper published Over Sea, Under Stone, the first book in The Dark Is Rising series, in 1965; three years later Ursula K. Le Guin published the first volume of her Earthsea series, A Wizard of Earthsea. Cooper and Le Guin seconded Tolkien’s exploration of evil and confronted subjects that became dangerous, almost taboo, by the late 1970s, especially the place of individuals capable of making glamour (particularly from nature), the “natural” role of so-called gifted people, and the responsibilities and tribulations of sensitive people who now and then glimpse glamour and its making although they cannot make it themselves.34

Visual realms, faerie, fantasy, and the ways some people make glamour or descry people making glamour order the work of Cooper, Le Guin, Ende, and Pullman. All perhaps owe a debt to the English painter and novelist Mervyn Peake, who began his Gormenghast series with Titus Groan in 1946, followed by Titus Alone thirteen years later, and Gormenghast in 1967.35 Peake’s work and that of the others emphasize envisioning and re-envisioning as th...