![]()

1

Classical Burlesque and Homeric Epic

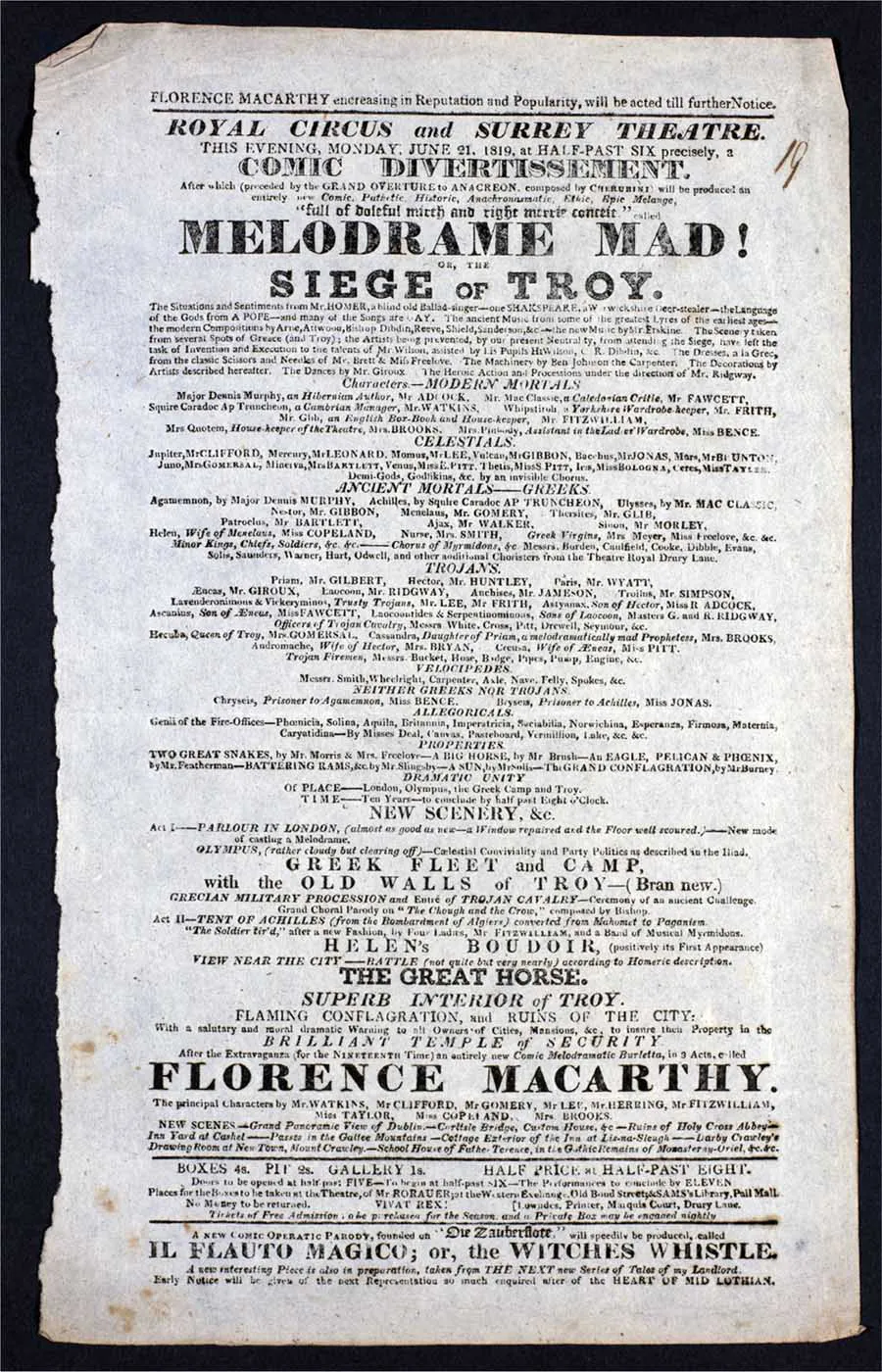

On 21 June 1819, exactly four weeks after the birth of Queen Victoria, London’s most prolific dramatist was eagerly anticipating an epic success. He had been raking in the profits with his burlesque versions of Sir Walter Scott’s bestselling novels, hot off the press. But now, Thomas John Dibdin was fed up. As he would bitterly recall in his memoirs, as soon as he advertised his latest adaptations, they were scooped by rivals.1 In some chagrin, this ever ‘resourceful and alert’ owner-manager of the Surrey Theatre produced a trump card.2 From repackaging the newest fiction, he turned to Western literature’s oldest and most revered poem: Homer’s Iliad. Only a few days after his latest novel dramatization was emulated by his newest competitor, the Royal Coburg Theatre (now the Old Vic), Dibdin’s advertisements triumphantly announced ‘an entirely new Comic, Pathetic, Historic, Anachronasmatic, Ethic, Epic Melange’ (Fig. 1). Despite the haste of its composition and rehearsal, newspaper critics praised Melodrama Mad! or, the Siege of Troy as ‘the best burlesque we ever witnessed’.3 Thanks in large part to the success of Dibdin’s adaptation of this most canonical of poetry, his minor venue in Lambeth – usually packed with sailors, office-clerks and mechanics4 – became the unexpected hit of the fashionable season: Melodrama Mad! was repeatedly requested by royalty for special ‘command performances’, as well as mimicked by schoolboys for their privately published amateur dramatics, and would be recalled by newspaper pundits four decades later as the yardstick by which to measure Victorian epic burlesques.5 At the same time, Dibdin’s title and description pilloried the current state of popular drama, which censorship restricted to a ‘miscellaneous collection of illegitimate genres’ (such as melodrama), but then denounced for ‘theatrical decadence’.6

Burlesques – comedies which aim ‘to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects’ (OED) – were extremely fashionable and highly lucrative in nineteenth-century Britain; especially in London, where the rapidly rising population inspired ever more entrepreneurs to open their doors for public entertainment. Adverts clearly show that burlesques were most often the central segment in a whole evening’s entertainment, which could be enjoyed quite cheaply and would end late (Vestris’ innovatively early end time of 11 p.m. at the Olympic was welcomed by her respectable clientele).7 These plays were dynamic, highly energetic and consistently humour-driven. They mostly adapted well-known plots using ‘slang, topical allusions, and domestication of character and situation’.8 Written for a traditional proscenium stage with theatrical orchestra and stage effects including transformation scenes, trapdoors and panoramas, they could consist of many scenes, which each showcased different backdrops and ended in a breakdown dance. Most burlesques would take around 60–90 minutes to run, although the multiplicity of non-verbal components make it difficult to estimate timings.9 The Morning Post’s praise of Dibdin’s incorporation of ‘A Superb additional Military Band, and the Choral strength of Drury-lane’ as well as the ‘grandeur of style, highly creditable to the Artists’ evident in the ‘conflagration of Troy, and the appearance of the gigantic horse’ demonstrates how integral such elements were to burlesque’s popular appeal.

Figure 1 Playbill of Thomas Dibdin’s Melodrama Mad! at the Surrey Theatre (1819) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

However, legislation did not keep pace with demand. From 1737 until 1843, only two venues in London which held Royal patents (Drury Lane and Covent Garden) were allowed to stage uninterrupted spoken drama: in fact, in the few years prior to Melodrama Mad!, a flurry of spies for these two royally endowed venues spitefully reported excessive unaccompanied and unsung dialogue at several ‘illegitimate’ theatres including the Surrey; such bitter claims and counter-claims escalated over the next decade as Covent Garden and Drury Lane fought to protect their exclusive stranglehold on traditional drama.10

Ironically, the censorship imposed by the Licensing Act of 1737 not only preserved many burlesque scripts which are now available to study at the British Library and Huntington Library, CA. In addition, these constraints motivated the creation and popularity of different sorts of performance, which consisted of more than spoken dialogue and were therefore not classified as plays. Rebelling against this ban on continuous spoken drama, the ‘illegitimate’ or ‘minor’ theatres combined song, dance and slapstick pantomime with wide-ranging allusions to topical talking-points, and wholesale parodies of the banned dramas. The resultant entertainments, labelled burlesques, burletta and extravaganza – which Planché simply defined as ‘whimsical treatment of a poetical subject’ – were often indistinguishable:11 in 1824, when he became Examiner of Plays, the ‘successful and highly experienced playwright’ George Colman the Younger struggled to decide, along with the Lord Chamberlain, the precise ratio of songs, verse and speech to enforce in burlettas.

Classical antiquity dominated the cultural and political landscapes and so it is unsurprising that many of these entertainments presented classical characters and stories, drawn from mythology, literature and history. Dibdin’s choice of epic subject was commercially driven – to reclaim the impatient crowds of spectators who flocked to successive performances of Scott’s Waverley novels. As such, he capitalized on the popularity of the Trojan War myths and the cultural prestige of antiquity in nineteenth-century Britain, as well as the long-standing tradition of satirizing canonical literature (especially the Iliad). The success of Melodrama Mad! in 1819–20, and the excitement engendered by the other three burlesques in this anthology, underscore the profitability of Homeric epic.

At the same time, critics throughout the century would question the...