![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE

The aim of Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror expedition was to find a North-West Passage – a sailing route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific across the top of North America. By the early nineteenth century the British Navy had explored nearly all the oceans of the world and the discovery of a North-West Passage was one of the greatest challenges that still remained.

1.1 Globe of the world

Malby & Co, 1845

This globe, claiming to show ‘all the recent geographical discoveries’, was published on 1 June 1845, less than two weeks after Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror voyage began. The unexplored areas appear to be free of obstructions, giving the impression that completing the North-West Passage should be quite straightforward. Comparison with the NASA image opposite reveals what was still unknown at that time.

Captain James Cook, during his third voyage, had been attempting to discover a North-West Passage by entering from the Pacific and sailing east. Cook was killed in Hawaii in 1779, three years into the expedition, and before long the Royal Navy was fully occupied with the American and French revolutionary wars. In 1817, less than 40 years after Cook’s death, when Greenland whalers reported that the Arctic ice had thawed to an unusual extent, the British Admiralty decided to resume the search for the passage for a number of reasons.

There was some hope that it might be useful for trade or for moving naval vessels around the world during the brief Arctic summers, with the potential to cut months off the time it took ships to sail from Europe to the west coast of America or China by going all the way round Cape Horn or through the straits of Magellan. It was also thought that the North-West Passage might provide quicker access to the coastal regions of the vast territory held by the Hudson’s Bay Company (a fur-trading organisation) on behalf of the British government. National prestige was another motive, since at this time the Hudson’s Bay Company ran up against the territory of the Russian-American Company (which operated in Alaska before Russia sold it to the United States later in the nineteenth century), and Britain wanted to show Russia that it was the dominant power in the region. Britain was also keen to enhance its reputation as a world leader in scientific and geographical discovery.

Before Sir John Franklin set out with Erebus and Terror in 1845, the British Admiralty had sent out a series of expeditions to investigate the Arctic coasts and navigable channels over a period of more than 25 years. The explorers’ tracks seemed so tantalizingly close to joining up that Franklin’s expedition was confidently expected to make the final breakthrough.

John Franklin had taken part in the very first of the new series of Arctic exploration voyages in 1818. He was commander of one of the ships sent to sail past Spitsbergen, an island in northern Norway, towards the North Pole, while another expedition went to Baffin Bay to explore routes leading west. The Spitsbergen voyage was disappointing. Captain David Buchan in HMS Dorothea, accompanied by Lieutenant Franklin in HMS Trent, encountered an ice sheet not far north of the island. Although they forced their ships into narrow channels in the ice and made painful progress by using their anchors and windlasses to drag their ships along, the mass of ice ultimately made their mission impossible. Both ships narrowly escaped being wrecked when they were driven against pack ice in a gale.

1.2 NASA satellite image of summer Arctic ice coverage

The satellite image reveals landmasses at the south-west end of Lancaster Sound (the main channel entering from the east) that had not been discovered by 1845. It also shows that, even after the dramatic shrinkage of the Arctic ice sheet since Victorian times, any attempt to sail north from Lancaster Sound would be blocked by ice.

Meanwhile, Commander Ross in HMS Isabella and Lieutenant Parry in HMS Alexander charted Baffin Bay. Ross then entered Lancaster Sound on its west side, and sailed westwards for part of a day, with Parry’s ship following several miles behind. In the afternoon Ross thought he could see mountains blocking the way ahead and, with the weather deteriorating, he decided to turn back without investigating thoroughly. However, others on board the ship were less convinced that it was a dead end and made their views known to the Admiralty when they returned. As a result, Edward Parry was sent out again the following year to settle the matter. After entering Lancaster Sound, his two ships, HMS Hecla and HMS Griper, were able to sail right through the charted locations of the mountains that Ross thought he had seen, proving that they did not exist. Parry’s expedition continued westwards, passing the meridian of 110 degrees west of Greenwich and claiming the parliamentary reward of £5,000 for having done so. As winter approached, Parry found a natural harbour for his ships so that they could stay in the Arctic rather than returning home – the first time that British naval vessels had done this. The expedition was therefore in a good position to make an early start in the spring, and the ships succeeded in progressing further westwards before being blocked by ice and having to go back the way they came.

While Edward Parry was exploring by sea, the Admiralty sent John Franklin, along with four other members of the Royal Navy, on an immense overland journey to the shore of the Arctic Sea in order to survey the coast. They set out from Hudson Bay in 1819, walking and travelling by canoe along waterways towards the Coppermine River. The distance was so great that the party took two years to reach the river as it was impossible to travel in winter and they had to spend several months of each year under cover, waiting for the snow to thaw. In summer 1821 Franklin’s men, assisted by voyageurs (French-Canadian boatmen) and indigenous guides, worked their way downstream and arrived at the mouth of the Coppermine River, where they launched two large canoes onto the sea. They headed east and succeeded in charting about 550 miles of new coastline. Their return journey was disastrous: at least nine of the 20 men died of starvation and two others were shot dead.

Franklin eventually arrived back in England in 1822, the year after Edward Parry returned to the Arctic on a second voyage with HMS Hecla and HMS Fury. The aim this time was to enter the Arctic Sea further south than through Lancaster Sound, by finding a passage through the north of Hudson Bay that led to the Arctic coast of North America. The ships found the entrance to a channel, which Parry named Hecla and Fury Strait, but although they overwintered twice they found that it was frozen all year round and they were unable to go through.

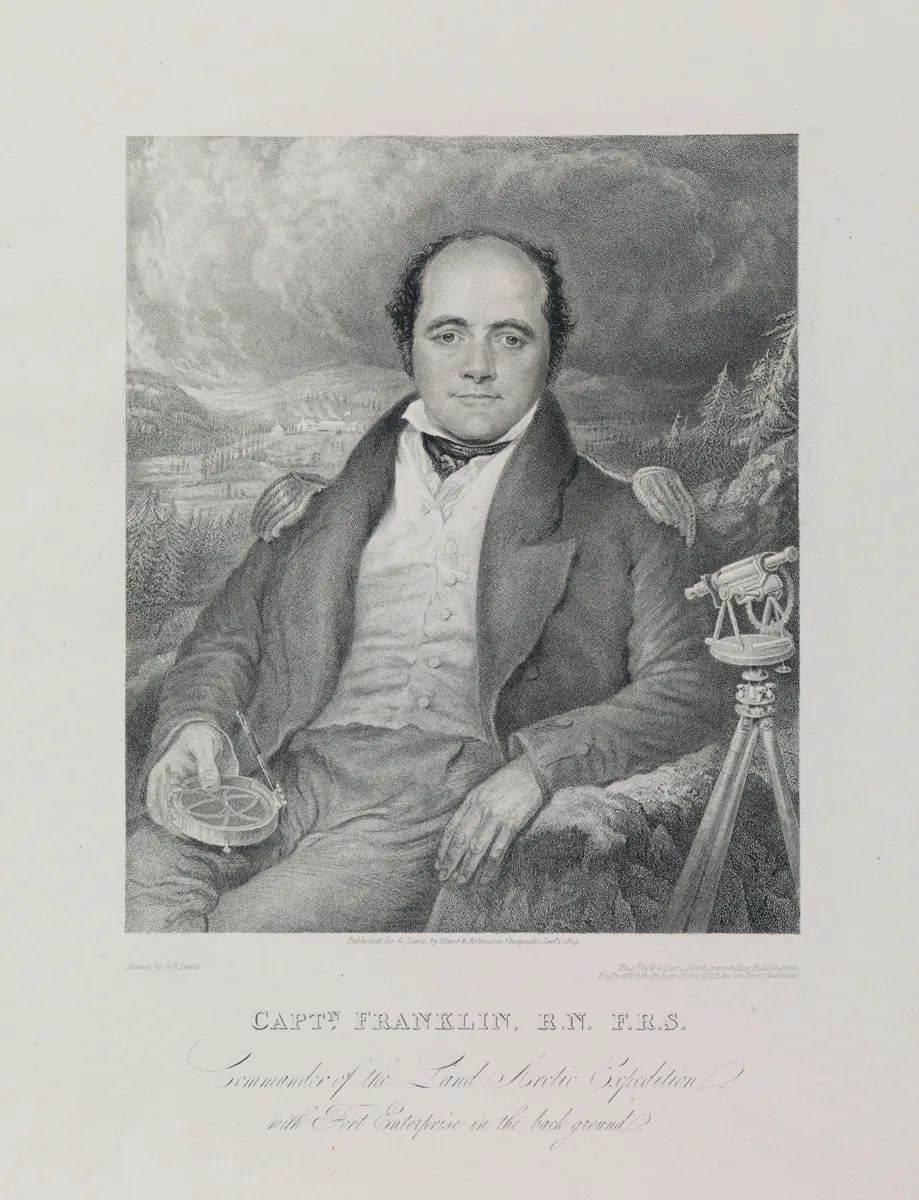

1.3 Captn Franklin RN, FRS Commander of the Land Arctic Expedition with Fort Enterprise in the background

Frederick Christian (engraver), after George Robert Lewis, 1824

John Franklin took part in his first Arctic voyage in 1818 and then, in 1819–22 and 1825–27, led two immensely long and arduous overland expeditions to chart the north coast of mainland of North America. In this picture Franklin is shown with surveying instruments, with the winter camp he built in 1820 in the background.

1.4 Captain Sir William Edward Parry (1790–1855)

Charles Skottowe, c.1830

William Edward Parry (always known as Edward) made three voyages in search of the North-West Passage, of which the first was the most successful, sailing west beyond 110 degrees of longitude and so winning a parliamentary prize. He was the first to plan for overwintering in the ice so that his ships could take advantage of more than one sailing season.

In 1824 Parry made a third voyage, again with Hecla and Fury. He aimed to enter Lancaster Sound then turn south down the first navigable channel, named Prince Regent Inlet. Bad ice conditions prevented the ships from entering the inlet in the first season and the crew had to saw them out of the ice the following July. The ships then made some progress south, but gales and drifting ice drove Fury aground and the ship was abandoned, damaged beyond repair. With the crews of both ships now on board Hecla, Parry sailed further south and saw clear sea ahead, but decided to turn back to be sure of a safe return.

As Parry was returning home in 1825, Franklin was beginning his second overland expedition to chart the north coast of the mainland. This time he reached...