Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), as developed by A. T. Beck and others, is built on the assumption that thinking processes both influence and are influenced by emotional and behavioural responses in many different psychological problems. Therapy therefore aims to modify cognitive, emotional and behavioural processes in an experimental way to test whether modification has positive effects on the client's difficulties. While clients may come to therapy asking for help with their negative thoughts, more often they come because they are feeling bad. Despite its focus on thinking, CBT is actually all about reaching and working with emotion. Cognitions and cognitive processes are emphasised because they can often provide direct and useful paths to relevant emotions. Furthermore, understanding specific thoughts, styles and processes of thinking can go a long way to explain negative feelings to clients, who may well have been experiencing them as incomprehensible and frightening. The way in which cognition influences emotion and behaviour is at the heart of CBT and the basis of both the early models, developed in the 1970s, and current theory and practice.

Since the first models evolved, both the theory and practice of CBT have been subject to continual and accelerating change and development. In this chapter, we look first at the foundational model of theory and practice and then at the subsequent developments leading CBT to what it is today. Such developments are now multifarious and include integration of the interpersonal and the therapeutic relationship within both the theory and practice of CBT. In addition, contributions have come from behavioural and cognitive theorists that have added new dimensions through increased understanding of the role of cognitive and emotional processes in psychological disturbance (Wells, 2009) and mindfulness in psychological change (Segal et al., 2002). After almost 50 years, the theory and practice of CBT are still developing, with what has been called the ‘third wave’ hitting the beach (Hayes et al., 2004). The chapter ends by looking at some of these new contributions, the ‘third wave’, bringing an experiential focus, mindfulness and acceptance to the practice of CBT.

Foundations of CBT

With his two major publications of the 1970s, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (1976) and Cognitive Therapy of Depression (Beck et al., 1979), Beck, and his colleagues, established what many now regard as the original model of CBT. The model contained a theory of how people develop emotional problems; a model of how they could heal disturbance; and a model of how further problems might be prevented. The links between emotion and cognition were initially most clearly demonstrated in the treatment of depression; opportunely because depression is often regarded as one of the most frequently presented psychological problems. The model was also supported by what was, for the psychotherapy field, an impressive range of research validation for both its underlying constructs and its outcomes.

The Thought–Emotion Cycle

A key aim in CBT is to explore the meanings that clients give to situations, emotions or biology, often expressed in the client's ‘negative automatic thoughts’ (NATs). The valuable concept of cognitive specificity (see www.sagepub.co.uk/wills3 for material on this and related definitions) demonstrates how particular types of thoughts appraise the impact of events on the ‘personal domain’ (all the things we value and hold dear) and thereby lead to particular emotions, as shown in Table 1.1. It is then possible to discern the influence that such thoughts and feelings have over behaviours – especially ‘emotion-driven behaviours’ (Barlow et al., 2011a). The appraisal of ‘danger’ to our domain, for example, raises anxiety and primes us for evasive, defensive or other reactions. The appraisal of ‘loss’ is likely to invoke sadness and mourning behaviour. An appraisal discerning ‘unfairness’ is likely to arouse anger and may lead to an aggressive response.

In themselves, responses to negative appraisals are not necessarily problematic and indeed are often functional: for example, we all know that driving carries certain risks and being aware of those risks may, hopefully, make us better drivers. Our specific appraisals of events may begin to be more problematic, however, as they become more exaggerated. If we become preoccupied with the risks of driving, and see ourselves as likely to have an accident, then the emotion of slight, functional anxiety becomes one of unease or even panic. Furthermore, if this feeling increases, the chances that driving ability is adversely affected also increase. Similarly, we may feel a certain comforting sadness about a loss in our life, but if we begin to see the loss as a major erosion of our being, we could then feel corrosive depression rather than relatively soulful melancholy. If the depression cycle goes on, we tend to become lifeless, lacking energy and enthusiasm, and are thereby less likely to engage in things that give our life meaning; as a result we become even more depressed. In another example, appraising meeting people as ‘worrying’ raises anxiety and primes evasion and defensiveness. If we become preoccupied with the risks of meeting people and making faux pas, then a sense of reasonable caution can become unease or even panic. Furthermore, if this feeling increases, the chances of our making faux pas may increase, which further increases our anxiety and so maintains the problem.

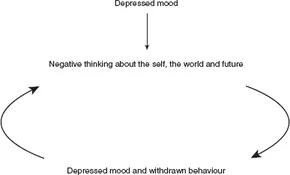

The essence of the model is that there is a reciprocal relationship between emotional difficulties and seeing events in a way that is exaggerated beyond the available evidence. These exaggerated ways of seeing things tend to exacerbate negative feelings and behaviour, and may constitute a vicious cycle of intensifying emotionally driven thoughts, feelings and behaviours (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 A Vicious Cycle of Thoughts, Feelings and Behaviour

Critics sometimes wrongly regard CBT as being based on generalised formulae that claim people are disturbed by their thoughts. In fact, good CB therapists understand each client in a highly individualised way. Rather than reducing clients’ mediating cognitions to formulaic sets of ‘irrational beliefs’, a CBT approach aims to understand why clients are appraising events in particular ways and why they feel the way that they do. In Epictetus’ famous dictum – ‘People are disturbed not by events themselves but by the view they take of events’ – external and internal (i.e., thinking about something) events are important because they are usually the triggers that set off the whole cycle of reaction. The same event, however, may impact differently on different people because, first, each individual has a different personal domain on which events impinge. Second, each person has idiosyncratic ways of appraising events because cognitions, perceptions, beliefs and schemas will have been shaped by that individual's unique personal experiences and life history. The aim of CBT is to understand both the client's personal domains and their idiosyncratic way of appraising events. Additionally, when we look to modify cognitions, it is probably impossible to completely erase negative thoughts. Pierson and Hayes (2007) make a valuable point when they say that it is not so much that clients have to replace a negative thought with a more functional one, but they are able to follow it with a more balanced thought – learning to allow the thought ‘I am a failure’ to be followed by another thought like ‘Hang on, that's not the whole story!’. Another account of the process of cognitive change comes from Brewin et al. (2006), who suggests that different cognitions are available at any one point in time but some – the more functional ones – are often difficult for depressed clients to retrieve. In this account CBT does not directly change cognitions but rather changes the relationship between different cognitions in such a way that more helpful ones are retrieved.

While, on a simplistic level, a person's thoughts and emotions about an event may appear ‘irrational,’ the response may be entirely rational, given his way of seeing the world. As we look at new developments in CBT, we will see that it may be that the content of the thinking itself is not so problematic. It turns out that, perhaps in a good, democratic fashion, ‘irrational’ content is by no means confined to people with psychological problems. For example, the thoughts that are problematic for clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are shared by 90 per cent of the population (Rachman, 2003). OCD sufferers, however, pay attention to these thoughts in a different way. Non-sufferers can let them go: OCD sufferers cannot. Similarly, it seems that most people at times have the kind of intrusive thoughts that are a problem for ‘worriers’ (Leahy, 2005). People vulnerable to worry, however, will focus more time and attention onto the worries and will be less able to let them go (Wells, 2009).

Cognitive Distortions: Negative Thoughts

Cognitive themes are expressed in specific thoughts. Rather than thinking in literal sentences, such as ‘There is a loss to my personal domain’, such themes are expressed in situationally specific cognitions (e.g., ‘He finds me dull’) that, when added together, amount to a theme (e.g., ‘People find me tedious’). These themes become elaborated and maintained by the day-to-day ‘dripping tap’ effect of the client's ‘negative automatic thoughts’ (NATs). Often the client is barely aware of these thoughts until they are highlighted. Beck (1976/1989) discovered the constant commentary of negative thoughts when a client became anxious while talking about past sexual experiences. The client, however, revealed that it was not the fact of describing these experiences that was causing the emotional pain but rather the thought that Beck would think her ‘boring’. In depression, thinking has a characteristically negative and global tone centred on loss – not just of loved objects but of a sense of self-esteem and, crucially, for depression, a sense of loss of hopefulness about the world and the future. The triangle of negative views of self, of the world and the future comprise Beck et al.'s (1979) ‘cognitive triad’, in which the dynamics of depression operate.

In an early publication Beck (1976/1989) described a range of cognitive distortions, shown in Table 1.2. For example, the thought, ‘I'm stupid’, a common negative automatic thought in emotional disturbance, betrays ‘all-or-nothing’ thinking because it usually refers to a narrower reality – that people occasionally do some things which, with the benefit of hindsight, may be construed as ‘stupid’. Depressed clients, however, will often go on to the globalised conclusion that this makes them a ‘stupid person’. In this type of dichotomous reasoning, there are only two possible conditions: doing everything right and being ‘not stupid’ or doing some things wrongly and being ‘stupid’. Thus the negatively biased person uses self-blame, thereby depressing mood even further in a vicious cycle.

In CBT, clients and therapists work collaboratively to identify and label negative thoughts and to understand how thoughts interact with emotions to produce ‘vicious cycles’. These are the first steps that enable clients to understand their emotions. When clients detect specific thoughts, it can be useful to ask them what effect these repetitive thoughts will have on their mood. Many clients will conclude that such thinking is bound to get them down. Thus the simplest form of the cognitive behavioural model links thoughts and emotions most relevant – salient – to clients’ situations. Therapists can then look at the degree of ‘fit’ between thought and feeling – does the thought make sense of the feeling? Looking at Table 1.2, if you had the thought, ‘I will lose my job’, would you be likely to feel anxious and worried? Clients may also have ‘favourite distortions’ – and this may allow them to take the helpful ‘mentalisation’ (being able to understand the mental state of oneself or others) step whereby they can say to themselves ‘There I go – personalising things again!’ As we will describe later such steps may be part of a wider ability to look at, defuse or decentre from negative thoughts from a new, more mindful position.

From Thoughts to Schemas

NATs are unhelpful cognitions closest to the surface of consciousness and may refer only to a limited range of situations. Beck recognised, however, that there were also deeper cognitions that incline the person to interpret wider ranges of events in relatively fixed patterns. Originally Beck used the term ‘constructs’ (Kelly, 1955) to describe deeper cognitive processes but then preferred the term ‘schemas’ used by earlier psychologists (Bartlett, 1932) to describe them.

Schemas are not, of course, all problematic. For example, Bowlby (1969) describes how children who have experienced satisfactory attachment and bonding to primary caregivers will develop a basic set of rules or schemas that contain the inner working model that ‘people can generally be trusted’. If people with ‘trust schemas’ meet untrustworthy behaviour in others, they are likely to think ‘Something went wrong there, I may have to be more cautious in future’, which is an adaptive response. When people with ‘mistrust’ schemas encounter untrustworthy behaviour, however, they are likely to conclude ‘I was right. You can't trust anyone. I won't do so again’, which is an overgeneralised and, therefore, less adaptive response.

Negative schemas are seen as underlying NATs. Unhelpful assumptions – conditional core beliefs – are operationalised into ‘rules of living’ and sometimes termed ‘intermediate beliefs’. They are contained within schemas, are triggered by events and lead to NATs. Sometimes the assumptions persist after NATs and the other symptoms of depression have abated and may then be targeted as a method of preventing later relapse back into depression. Whilst these different levels of cognition are conceptually clear, in practice they are usually identified from client self-reports and therefore it is not always easy to know if the thought ‘I am a failure’ is truly a core belief or a thought that applies to only limited situations.

As CBT developed, schemas were given a more significant and autonomous role in therapy. It is important to remember when working with schem...