![]()

1

Painting in action

Ben, aged two, stands at a low table on which there is a sheet of paper and two pots of paint, one green and one blue. In each pot stands a paintbrush. First of all, Ben picks up the blue brush with his right hand and paints with it, using a vigorous fanning or arcing action from side to side across the surface of the paper. This action creates an elongated curved blue patch, like an arc of a large circle. His whole body seems involved in this energetic painting action.

The brush never leaves the surface of the paper but every now and then Ben abruptly changes his sideways fanning action to a pushing and pulling movement, to and from his chest. The paintbrush therefore moves in two opposing directions, from side to side, creating the blue arc, and this new, back and forth movement, crossing it at approximately 90 degrees, giving it a jagged contour.

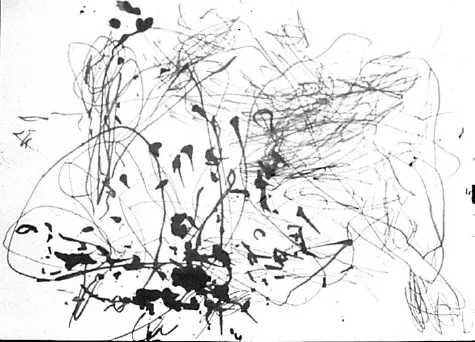

Ben then puts this blue brush back in the pot and picks up the green brush. As he carries it over the painting, paint drips from it, leaving a trail of green spots across both the table and the painting. He notices this and immediately shakes the brush above the painting, making more green spots fall onto the white paper. In the meantime, Linda, his mother, has prepared a pot of red paint for him and has placed it, with a brush inside, on the table next to the other two pots. Picking this red brush he makes further arcing movements over the blue patch. The red mixes with the blue to make a brownish colour. He momentarily stops painting, and points with his left index finger to a particular part of the painting. The focus of his attention appears to be a section of the painted patch’s irregular edge which his paintbrush has just produced. ‘There’s a car there’, he says (see Figure 1).

Ben stops only for a moment, however, returning to his painting to make variations and combinations of the actions he has already produced. Arcing movements now flow into zigzag movements. The brush remains in contact with the paper, even when, for a moment, he looks up at me and smiles.

Figure 1 ‘There’s a car there’, by Ben, aged two

Figure 2 ‘It’s going round the corner’, by Ben, aged two

Quickly turning back to his painting, Ben suddenly makes a quite different painting action. His brush describes a series of continuous, clockwise rotational movements. The first revolution runs right through the patch to which he had just referred as the ‘car’. Each succeeding rotation almost coincides with the previous one. As he makes this continuous rotation he says, ‘It’s going round the corner … It’s going round the corner … It’s gone now’ (see Figure 2). He then dips the brush into the red pot again and aims it into the roughly circular closed shape he has made. He repeatedly plonks the brush down with a quick, rhythmical stabbing motion. This makes red blobs appear in and around the centre of the closed shape (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Ben, aged two, makes marks inside a closed shape

Ben then vigorously smears these red blobs with the same brush, using that same horizontal arcing motion again. Very soon, the rotational shape and the small sector of white paper, which up to now remained within it, are obliterated under this energetic side-to-side movement of the brush.

Some questions

The above painting episode is typical of a kind practised by many two- to four-year-olds (Matthews, 1983; 1984; 1999). What does it mean? Is it a haphazard, random sequence of actions, without meaning? Is it mindless ‘scribbling’? Many people would say that Ben is just messing around with paint. They might feel that this is neither an organised abstract design nor a drawing. Drawing, they might argue, is about making recognisable pictures or ‘accurate’ representations of objects, scenes and people. This child surely cannot be representing anything, since his painting is not a ‘picture’ of anything which we can recognise.

Even seeing Ben in the process of painting and hearing what he says about it would still fail to impress many people that anything significant was happening. They might agree that Ben enjoys this impulsive activity, but argue that it is just the clumsy beginnings of a long apprenticeship towards ‘correct’ drawing and painting. True, they might say, his actions seem intense, but surely much of his body movement is completely irrelevant to what drawing and painting are really about?

It is also true to say that he talks excitedly about the painting, but what is he talking about? Surely the only accurate term he uses is ‘round’ and we might expect young children to name a few shapes which accidentally occur in their paintings. How do we know that his words correspond to his painting? He mentions a ‘car’ but where is the ‘car’? There does not appear to be a shape which accurately corresponds to a shape of a car. Surely his words are inappropriate and only have meaning for him?

This, after all, is the message given to us by the vast majority of books about the ‘stages’ of children’s drawing development. Some writers on children’s art acknowledge early mark-making as having emotional importance, or importance in terms of finding out about art materials, or in terms of the co-ordination of body movements and being able to use a paintbrush or pencil, but very few of them consider it to be the beginnings of visual representation or expression. Usually, it is called the ‘scribbling’ stage. One theory claims that scribbling is important only in so far as the child notices, and perhaps speaks about, accidental – or ‘fortuitous’ – likenesses appearing in the marks he or she has made. This theory continues with the child supposedly trying to purposely repeat what was initially the product of accident. This, in itself, is a startling idea, because, unlike what we know of any other aspect of intellectual development, the move to representation, from no representation at all is, according to this notion, simply a matter of accident. We will see later that accident does indeed play an important part of children’s expression and representation, as it does in development overall, but not in the way it is described in the traditional theory.

A variation of this approach also starts with the notion that scribbling is important only in so far as it accidentally supplies a vocabulary of shapes out of which the child will, later on, make designs and pictures (Kellogg, 1969). According to this approach then, Ben’s present painting actions, his actions in the here and now, are not in themselves important. They have significance only in terms of their supposed use later on in development. The explanation here would be that Ben stumbles upon the ‘round’ shape, recognises it as round (even uses the word ‘round’) and uses this and other shapes also discovered by happenstance as ‘building blocks’, put together to make designs and pictures of various kinds, perhaps months later. Although commonly accepted as an explanation, no one seems to have evidence that this process actually occurs (Cox, 1992; 1993; 1997). Ben uses the term ‘round’ as a verb, and as part of a sentence which describes an event. This is inexplicable in terms of either ‘fortuitous realism’ (accidental resemblances to things in the real world) or the theory that scribbling supplies a pool of geometric shapes for later compositions.

If people generally think the beginnings of drawing are disordered scribbling without meaning, then later drawings fare little better with many writers. Although children gradually learn to make pictures which adults think they recognise as attempts to represent views of objects, these images are at best regarded, in an uncritical, sentimental way, as charming or, worse still, thought to be full of errors. They are measured against a sort of checklist to see how well they conform to a notion of ‘accurate representation’.

Sometimes, these attitudes are biased towards a restrictively Western European approach to representation originating from the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century. Although the terms ‘visual realistic’, ‘accurate representation’ and ‘stages’ trip off many a researcher’s tongue, they are notoriously difficult to define and study.

The notion of ‘visual realism’ is not the only exemplar against which children’s representation is measured. Other sorts of prejudices about representation are implicit in many accounts of children’s drawing and influence the way people provide for the child to draw and paint. For instance, different societies might have different expectations of their children and these expectations will influence how children’s visual representation is received. What these different exemplars have in common is that they define and measure development against a presumed end point in terms of a representational norm sanctioned as ‘correct’ by society.

At times, the ways in which we look at children’s drawings and paintings conceals, rather than reveals, the meaning of painting episodes like Ben’s. Jerome Bruner (1990) has commented that some kinds of research simply go round and round in circles, merely supporting the assumptions they are supposed to investigate. This happens when we emphasise how near to ‘visual reality’ children’s drawings are, or compare them with some other notion of what makes for a ‘good’ or ‘accurate’ representation.

I believe that my research, over the last quarter of a century, in both London and Singapore, shows that children’s drawing has organisation and meaning all the way from the beginning, when many people consider infants to be scribbling (see front cover illustration (top row, 2nd from left) and Figure 3a).

The way we understand and provide for children to draw and paint needs to be rethought. This does not just apply to art education. Children, as they begin to draw and paint, make an intellectual journey which has musical, linguistic, logical and mathematical as well as aesthetic aspects. All these are endangered if we do not understand the development of drawing. The familiar, positive clichés about children’s art – that it contributes to cognitive development – are true. The problem has been that, as we shall see, with some notable exceptions (Smith, 1983; Wolf and Fucigna, 1983; Athey, 1990; Willats, 1997; Kindler, Eisner and Day, 2002 in press), few people have been able to say what this contribution actually is.

Figure 3a A drawing by Ben, aged two years and three months

Visual representation and expression

Most people would accept that early mark-making is one aspect of a baby learning the skills of handling and using materials. We have to decide whether we are justified in claiming that this is also the beginning of visual representation and expression. Some writers suggest that, given what we know about other aspects of development, it would be strange if drawing had no meaning for the child, right from the start (Wolf and Fucigna, 1983; Athey, 1990). For example, recent research strongly suggests that right from birth, the baby develops a range of communicative and representational possibilities in actions and vocalisation. We know that newborn babies seem to be able to take part in shared acts of meaning with caregivers (Stern, 1977; Trevarthen, 1980; 1995). They also seem quickly to develop understandings about events and objects. Their mastery of objects seems to emerge from meaningful relationships with people, especially the first caregiver (Trevarthen, 1975; 1995). We shall return to this later.

Drawing and language

Language development is often seen as a continuous process which has meaning and organisation all the way through from its beginnings. Although there are many contrasting theories of how we learn to speak, many linguists would agree that the development of language is a creative process which cannot be explained as a process of imitation, by the infant, of adult speech. The work of Noam Chomsky (1966; 1994) shows that, even though young children’s early speech might seem strange, it is the result of their active generation of language ‘rules’ which change as they grow older. We will see later the important analogy here to drawing development. Whether or not the notion of ‘rule-making’ is perfectly appropriate (for either language or drawing), and whether Chomsky’s idea that these ‘rules’ are represented in the brain in some way, is controversial. Nevertheless, Chomsky’s theory of the language acquisition as an essentially, creative process, in a technical sense, is very pertinent to drawing development. Children neither make sentences by copying older speakers, nor do they learn to draw by merely imitating adult pictures.

On the other hand, neither is development, in either language or drawing, completely idiosyncratic. Resolving the apparent contradiction between processes which seems to be at the same time both creative yet universal has been a perennial problem in describing development (Wilson and Wilson, 1985; Wilson, 1997). In any aspect of development, for example, learning to walk, children seem to move through similar sequences of development. We therefore expect children to start to walk around the first year, give or take a few months. Yet we each of us actually achieve our first steps in a unique way. The developmental route from crawling, or bouncing along on our bottoms, to cruising, to finally taking our first unsupported steps, is always individual and never predestined. How can these two aspects be simultaneously true? How can development in drawing, or in anything else, appear neat and orderly from a distance (to use Esther Thelen’s and Linda Smith’s apt way of putting it), yet messy and individualistic when viewed more closely (Thelen and Smith, 1994)? We clearly need better explanations than either the predictable ‘stage-by-stage’ theory, the imitation model or the notion that it is all totally individualistic. None of these are right.

Recent work in the origins of language also strengthens a link between language and other forms of representation. A long tradition in linguistics has been the notion that speech is a wholly arbitrary and conventional system of signs (unlike pictures, which resemble, in some way, the objects they represent). However, recent language studies offer evidence which suggests the origin of visual representation in a gestural language developed in infancy (Allott, 2001). This idea is very important for our later discussions about the beginnings and nature of visual expression and representation.

Scribbling and babbling

How then are we to understand what Ben is doing as he paints? When babies learn to speak, it might be the case that the rhythm, intonation and communicative patterns in babbling, along with the individual sounds, are carried over into the first true sentences (de Villiers and de Villiers, 1979; Allott, 2001; Thelen and Smith, 1994). I will argue that painting episodes like that of Ben, are grammatically articulated. He is obviously very involved in the painting at a level of communication and meaning. His whole manner suggests a commitment which would not be conveyed by mindless scribbling. What he is doing seems to be emotional. Perhaps it reflects or conveys his mood. Alternatively, it may help create a mood or, at least, intensify an existing one.

He seems to bring some understanding to the art materials he uses, and it is clear that he already knows a great deal about paint. He knows something about paint pots and brushes. He knows how to transport a paint-laden brush from the paint containers to the painting surface. He knows to reload the brush at intervals. Some kinds of knowledge, however, have been acquired in situations common to many children: investigating and playing with food and drink; studying the behaviour of water at bath-time. Ben knows a significant amount about contained liquids. It appears that drawing and painting actions are discovered from other actions previously explored. These earlier actions form a background upon which new actions are constructed. In turn, these new actions create further opportunities for more new actions, and so on. Drawing actions are members of a family of interacting expressive and representational actions formed against a history of earlier actions.

Ben has already learnt about the uses of the confines of the paper. For instance, he restricts most of his mark-making to this sheet. Arranging one’s attention and actions towards a blank sheet of paper in readiness for the act of painting might be taken for granted by an adult. Yet even a blank sheet of paper is a product of a theory about space and representation developed over many years by a society. Before brush has been set to paper, Ben, in his attitude and stance, is doing something just as intelligent as using painting tools. This means that he has already acquired some insights into a particular mode of expression and representation. There is nothing extraordinary about Ben in this regard. Many children aged between two and three years will be introducing themselves to, or be introduced to, painting, writing and drawing media. It does suggest, however, that the way in which children discover, or are introduced to, these media, is important and aff...