![]()

Chapter 1

KOREA AND THE COLD WAR WORLD

March 1951 opened with UN forces on the move across the Korean peninsula. Two months earlier the situation was much different. The success of the Inch’on landing in September 1950 and the subsequent destruction of much of the North Korean army and its equipment had turned to stunning failure for UN forces with the massive Chinese intervention in November. Battlefield defeat and a hasty withdrawal from North Korea in late November and early December were costly in terms of manpower and material losses. Even more important, potentially, was the effect on morale among soldiers and their leaders at all levels, from the battlefields in Korea to Washington. The Chinese intervention dramatically changed the nature of the war. What had been termed a “police action” in June 1950, indicating a measured response to an unlawful but limited threat by North Korea, had now become a full-scale war, with the potential for escalation to a Third World War between the United States, its allies, and the Communist world.1

Almost from the beginning, the conflict in Korea had been of secondary concern to the United States and many of its allies, who saw the greatest threat in Europe, not in the Far East. The Soviet Union, which had exploded a nuclear device in September 1949, seemed poised to invade the almost defenseless Western European countries from its Eastern European satellite states. National Security Council (NSC) paper 68, a wide-ranging study of the global situation facing the United States completed shortly before the North Korean invasion, concluded that the Soviet Union was a direct threat to United States interests, especially in Europe, and that substantial increases in military forces and expenditures were required. United States defense policy prior to NSC 68 had rested on the assumption that its monopoly of atomic weapons would lessen the need for conventional forces. Consequently, air, ground, and naval forces were weak, not only in numbers, but also in terms of training and equipment. President Harry S. Truman was embroiled in domestic economic problems, and his administration was fighting off accusations from Republicans, such as Senator Joseph McCarthy, that Communist traitors in the United States government had contributed to the loss of China to the Communists. Truman did not see where money could be found for increases in defense spending. Consequently, the administration’s priority of balancing the budget meant a one-third decline in projected Army spending for 1950.2

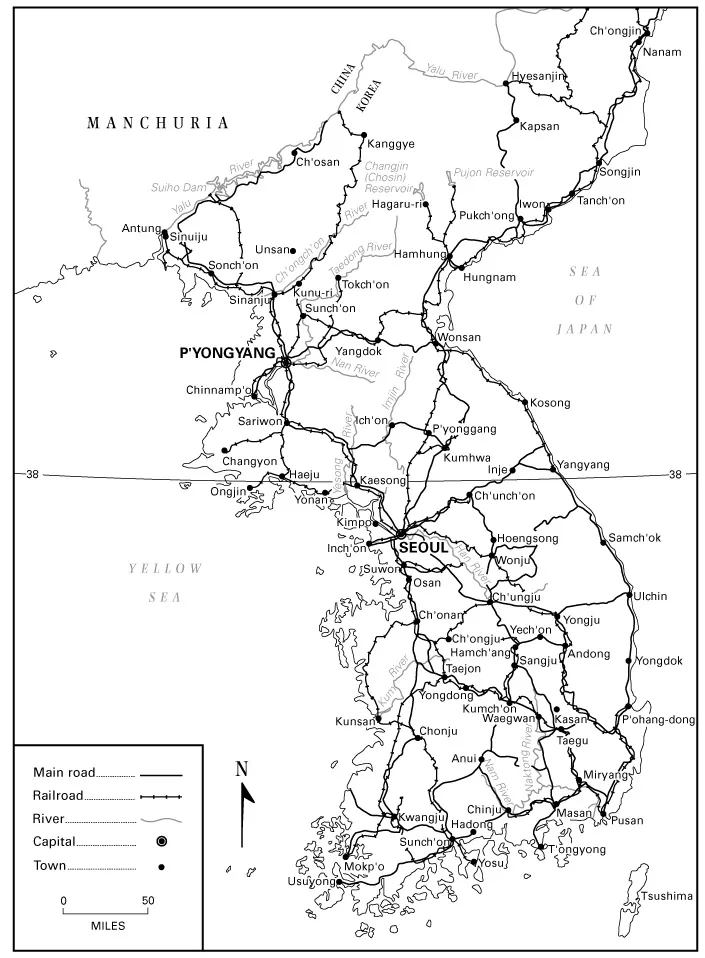

Korea (based on U.S. Army Center of Military History map).

Truman was shocked in June 1950 when North Korea attacked South Korea, an area considered outside the range of vital United States strategic interests. Incensed with this flagrant example of naked aggression, Truman was also mindful of how the failure to deal swiftly with German, Italian, and Japanese aggression in the 1930s had led to World War II. To Truman, the surprise attack of North Korea offered an opportunity to mobilize the American people and obtain congressional backing to respond to a Communist threat and support the increases in defense spending called for by NSC 68. Truman ordered a rapid reaction to the North Korean attack, both in military and diplomatic terms. Understrength American divisions in Japan were quickly moved to Korea and reinforced with soldiers and units from the United States, including one Marine and two Army divisions. United States air and naval units began attacking North Korean forces, and the U.S. Seventh Fleet moved ships to the Formosa Strait to support Nationalist China against the threat of a Chinese Communist invasion. On the diplomatic front, the United States introduced a resolution in the United Nations, which was passed on 27 June, calling on its members to assist South Korea in repelling the North Korean attack. Eventually, fourteen nations provided combat support to United States and South Korean forces, and five others sent medical assistance.3 But America’s allies were greatly concerned with the possibility of an expansion of the war outside of the Korean peninsula, and, to some extent, allied contributions to the fighting in Korea were designed to give them some influence in American decisions.

By September 1950 the ability to immediately reinforce Korea with additional forces from the United States was exhausted. The draft was expanded to fill depleted troop units in the States, and four National Guard divisions were called into federal service, but several months would be needed before these forces would be ready for combat. The outbreak of the Korean War and the pressing defense demands it created seemed to confirm the conclusions of NSC 68. In early September President Truman announced that defense expenditures would balloon from an estimated $13 billion per year in June 1950 to $287 billion over five years and that American forces in Europe would be increased by several divisions and two corps headquarters.4

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the American commander in the Far East and the Commander in Chief of the United Nations Command, was told that no additional forces would be sent to him. With the collapse of the North Korean army after the Inch’on landing in September, Truman directed MacArthur to cross into North Korea and move to the North Korean–Chinese border along the Yalu River, but to ensure that only South Korean forces entered the border area. Planning proceeded for withdrawing the bulk of United States forces from Korea, and one division, the 2d Infantry, was to be shipped to Europe. America’s European allies reluctantly supported the United States’ decision to turn from a policy of defending South Korea to occupying North Korea. As UN forces moved into North Korea, Soviet-built MIG jet fighter planes began to appear in the area, soon followed by Chinese Communist ground troops, which attacked United States and South Korean units in late October. Diplomatic signals by China, as well as intelligence reports, were disregarded, and the UN advance continued. MacArthur demanded and received permission from Washington to attack the bridges over the Yalu River, over which Chinese troops were crossing into North Korea. But on another matter, MacArthur disregarded his instructions and acted unilaterally by ordering United States forces to move directly to the Chinese border. After the fact, Washington approved this decision.

The Chinese attack in late November and the subsequent withdrawal of UN forces from North Korea greatly affected MacArthur and Truman. MacArthur’s unrestrained optimism before the attack turned to deep pessimism. He requested massive reinforcements and said that without them he would likely be forced to withdraw to a beachhead around Pusan at the southern tip of the peninsula, hinting that complete withdrawal was possible. In contrast, Truman’s fighting spirit was raised, and, at a news conference on 30 November, he told reporters that the United States would use every weapon in its arsenal, including the atomic bomb, to deal with the situation in Korea. The seriousness of the situation was apparent, with the danger of the fighting spreading to China and the Soviet Union and with the potential for the use of nuclear weapons.

Truman’s public threat to use nuclear weapons drew an immediate response from America’s closest ally, Britain. Prime Minister Clement Attlee immediately flew to Washington for meetings with the president. They reconfirmed that Europe remained the top priority and that they would strictly limit the scope of the war in Korea. Truman, however, refused to allow Britain a veto over the use of nuclear weapons, stating only that they would be informed before American use. MacArthur was told that no additional reinforcements would be sent to Korea. Truman then proceeded with a series of steps to mobilize the country. On 16 December he declared a state of national emergency. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Allied Commander for the military forces of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). European allies began to build up their military forces, including a limited rearmament of West Germany. Planning proceeded to move two corps headquarters (V and VII) and four divisions (2d Armored and 4th, 28th, and 43d Infantry) to Europe in 1951 to reinforce the U.S. Seventh Army, which had been activated in late November 1950 in Heidelberg, West Germany. The forces destined for Europe were to receive substantial training and the most modern equipment before their deployment.

In the midst of these measures, American public opinion, influenced by large casualty lists and a war with no clear end in sight, turned against the conflict in Korea. Criticism rose in Congress regarding the manner in which the Truman administration was prosecuting the war. There was little enthusiasm for the draft, for increased taxes, or for what seemed to be a greatly expanded activist role for the United States throughout the world. Reservists, many of whom were combat veterans of World War II, complained loudly that in Korea they were fighting their second war while new draftees were being readied for service in Europe. Because of pressure on Congress and the Army’s desire to maintain morale in Korea, a troop rotation system was established that would permit frontline soldiers to leave Korea after serving nine months in a combat unit.

The Soviet Union and Communist China proceeded cautiously after the defeat of the UN forces in North Korea. In early December, China informed the United Nations that it would agree to an armistice in Korea if the following conditions were met: UN forces withdraw from the peninsula, United States naval forces move out of the Formosa straits, Nationalist China be expelled from the UN, and Nationalist China’s UN seat be given to Communist China. The Soviet Union restricted its effort to logistical support of China and North Korea, and limited its participation in the air war over Korea, taking no steps to interdict American supply lines from Japan or to introduce its own forces into the ground war. China moved its forces forward toward the South Korean border, but it would take a number of weeks to build up the necessary logistical support for a renewed offensive to drive the United States and its allies from the peninsula.

On 23 December 1950, Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker, the American commander in Korea, was killed in a traffic accident. His replacement, Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, then the chief of operations on the Army staff in Washington, faced a formidable challenge. He was fully aware of the restrictions under which the war in Korea must be fought. There would be no reinforcements, although losses would be replaced; the war would not be expanded outside of Korea, effectively providing a sanctuary for enemy airfields and supply bases in China; and if defeats in Korea continued, in all likelihood a decision would be made to withdraw because Europe was the priority. En route to South Korea, Ridgway stopped briefly in Tokyo. MacArthur provided a pessimistic assessment: he was concerned that the UN lacked the capability to defend South Korea or even to erect a defensive line across the peninsula because of difficult terrain and a shortage of troops; air power could not be counted on to effectively interdict enemy supplies and forces; the Chinese must not be underestimated, for they were expected to renew their attacks in overwhelming force at any moment.5

Arriving in Korea on 26 December, Ridgway sensed defeatism from the moment of his initial briefings at Eighth Army headquarters. The only planning taking place was for further withdrawals to Pusan and evacuation from the Korean peninsula. Information on enemy locations, strength, and intentions was almost nonexistent. Over the next four days, a series of visits by Ridgway to corps and division headquarters provided additional signs: men were exhausted; morale was low; many seemed to have an exaggerated idea of enemy capabilities. In American units, many of which had been hastily assembled and shipped to Korea to deal with the crisis in the summer of 1950, too many soldiers and their leaders lacked fundamental combat skills; Republic of Korea (ROK) forces, which held two-thirds of the UN line, were largely untrained and unreliable; and reserve forces consisted only of newly raised, untrained ROK units and the U.S. X Corps and 2d Infantry Division, which had sustained heavy casualties in North Korea and were in need of time to absorb replacements. There was a noticeable lack of aggression in all commanders, except Maj. Gen. Ned Almond, commander of X Corps. But to balance this, there were reports that Almond was reckless, and the Marines, who had served under him in the harsh fighting around the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea, were firmly opposed to being part of Almond’s X Corps in the future. To complete the picture of a desperate situation, the Chinese and the rebuilt North Korean army began their new offensive the night of 31 December.

Ridgway was a capable combat commander, who had proven his skills leading first the 82d Airborne Division and then the XVIII Airborne Corps through tough and extensive combat operations in the Mediterranean and Europe in World War II. He was confident that, with time, the morale and fighting abilities of the UN forces could be restored. But now there was no time. The main enemy blow fell on the U.S. I and IX Corps north of Seoul, but the greatest potential danger was pressure building in the mountainous center of the UN line held by the ROK II and III Corps, where a breakthrough by the enemy would endanger UN lines of supply and of retreat extending south from Seoul to the port of Pusan on the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula. As the fighting erupted in the New Year, there was a real question whether the UN forces would be able to hold back the enemy and retain their position in South Korea.

The initial enemy attacks were successful. In the west, UN forces conducted a fighting withdrawal to the Han River but could not stop the enemy onslaught. Seoul was abandoned on 4 January. With pressure building to the front and the threat of envelopment from the east, Ridgway ordered the U.S. I and IX Corps to withdraw to a new defensive line some fifty miles south of Seoul. This move was designed to keep United States forces intact and to stretch Chinese logistics, which did not have the capability to sustain lengthy offensive actions. Ridgway planned to slowly withdraw while inflicting maximum damage on pursuing enemy forces; at the appropriate time he would counterattack.

The day before the fall of the South Korean capital, to deal with a threatened breakthrough in the central mountains, Ridgway ordered Almond’s X Corps to move into the area and take over a forty-mile front from the ROK II and III Corps, which had been badly mauled at the opening of the enemy offensive. With the U.S. 7th Infantry Division reorganizing from its withdrawal from North Korea, only the U.S. 2d Infantry Division was immediately available. On 7 January, North Korean forces attacked the 2d Division at Wonju, and over the next ten days fierce fighting took place just south of the town. To the east of the 2d Division, the enemy took advantage of a gap in the ROK lines to move the North Korean II Corps into the UN rear area between Yongwol and Andong, where it operated as a guerrilla force. Ridgway gave Almond the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (RCT) to deal with this threat, while the U.S. 7th Infantry Division joined ROK units to close the gap in the UN defensive line. The 1st Marine Division was also sent into the area to systematically eliminate the North Korean guerrillas. Late in January, the North Koreans pulled back to the Hongch’on area to regroup.

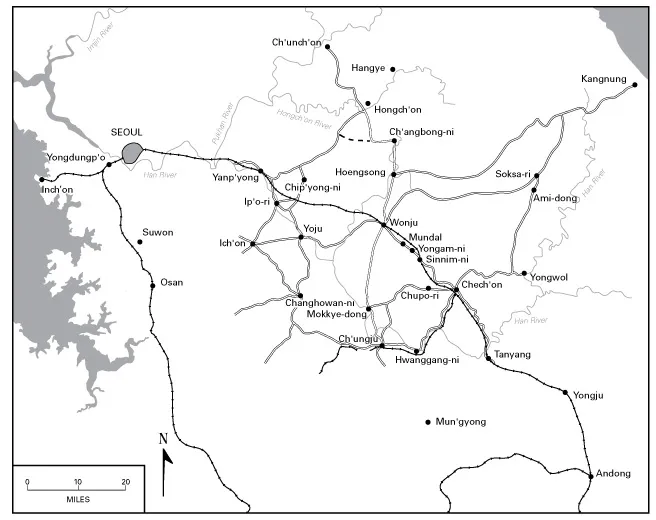

Area of operations, January–February 1951 (original map by author, based on U.S. Army Center of Military history map).

Meanwhile, south of Seoul, the Chinese had sent only patrols forward to follow the U.S. I and IX Corps. Ridgway was dissatisfied with the way his American units had conducted their withdrawal from Seoul; they had ignored his orders to maintain contact with the enemy and to inflict casualties whenever possible. To regain contact with the enemy and to restore a spirit of aggressiveness among his troops, he ordered a series of carefully planned reconnaissances in force. These actions began on 15 January; on 25 January Ridgway converted them into a deliberate coordinated advance called Operation Thunderbolt, which was designed to push north to the Han River to seek out and destroy enemy forces. On 29 January, Ridgway ordered X Corps to join the advance of I and IX Corps to protect their eastern flank.

General Almond planned to send ROK divisions assigned to his X Corps forward against the North Koreans reorganizing near Hongch’on. The ROKs were to be reinforced by American tank and artillery units and backed up by the U.S. 2d and 7th Infantry Divisions. Almond termed this eastward extension of Thunderbolt, Operation Roundup. The UN Command was unaware that the Chinese had moved into the central mountains to reinforce the North Koreans. Strong resistance developed along the IX and X Corps boundary. The IX Corps right flank unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, fought sharp engagements west of Ich’on at Hill 312 and elsewhere in late January. On 29 January and again on 1 February, the Chinese attacked elements of the U.S. 2d Infantry Division along the corps boundary just south of the key crossroads town of Chip’yong-ni. Despite indications of an enemy buildup and an awkward command control arrangement between the ROK divisions and their American artillery and tank support units, Ridgway allowed Almond to proceed with Operation Roundup. The ROK divisions began their advance on Hongch’on on 5 February.

Initially, the continuation of the UN advance proceeded smoothly. On the left, I Corps met little opposition as it reached the southern outskirts of Seoul. On the right, IX Corps advanced slowly against stiffening opposition and, by 9 February, had come upon a strong enemy defensive line along the high ground four to seven miles south of the Han River. Led by the 5th and 8th ROK Divisions, X Corps’ advance moved north from Hoengsong along the roads running through the mountains to Hongch’on. The 23d Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 2d Infantry Division occupied Chip’yong-ni to maintain contact between IX and X Corps.

By 11 February, Ridgway was concerned. He ordered Almond to halt his advance toward Hongch’on until the enemy bridgehead between the Han River and Ich’on in the IX Corps sector was eliminated. Intelligence reports indicated that, in addition to the North Koreans, the Chinese had concentrated four armies, some 110,00...