![]()

PART I

THE PART PLATED BT SOIL

FERTILITT IN AGRICULTURE

![]()

2

THE OPERATIONS OF MATURE

THE INTRODUCTION to this book describes an adventure in agricultural research and records the conclusions reached. If the somewhat unorthodox views set out are sound, they will not stand alone but will be supported and confirmed in a number of directions—by the farming experience of the past and above all by the way Nature, the supreme farmer, manages her kingdom. In this chapter the manner in which she conducts her various agricultural operations will be briefly reviewed. In surveying the significant characteristics of the life—vegetable and animal—met with in Nature particular attention will be paid to the importance of fertility in the soil and to the occurrence and elimination of disease in plants and animals.

What is the character of life on this planet? What are its great qualities? The answer is simple: The outstanding characteristics of Nature are variety and stability.

The variety of the natural life around us is such as to strike even the child’s imagination, who sees in the fields and copses near his home, in the ponds and streams and seaside pools round which he plays, or, if being city-born he be deprived of these delightful playgrounds, even in his poor back-garden or in the neighbouring park, an infinite choice of different flowers and plants and trees, coupled with an animal world full of rich changes and surprises, in fact, a plenitude of the forms of living things constituting the first and probably the most powerful introduction he will ever receive into the nature of the universe of which he is himself a part.

The infinite variety of forms visible to the naked eye is carried much farther by the microscope. When, for example, the green slime in stagnant water is examined, a new world is disclosed—a multitude of simple flowerless plants—the blue-green and the green algae—always accompanied by the lower forms of animal life. We shall see in a later chapter (p. 127) that on the operations of these green algae the well-being of the rice crop, which nourishes countless millions of the human race, depends. If a fragment of mouldy bread is suitably magnified, members of still another group of flowerless plants, made up of fine, transparent threads entirely devoid of green colouring matter, come into view. These belong to the fungi, a large section of the vegetable kingdom, which are of supreme importance in farming and gardening.

It needs a more refined perception to recognize throughout this stupendous wealth of varying shapes and forms the principle of stability. Yet this principle dominates. It dominates by means of an ever-recurring cycle, a cycle which, repeating itself silently and ceaselessly, ensures the continuation of living matter. This cycle is constituted of the successive and repeated processes of birth, growth, maturity, death, and decay.

An eastern religion calls this cycle the Wheel of Life and no better name could be given to it. The revolutions of this Wheel never falter and are perfect. Death supersedes life and life rises again from what is dead and decayed.

Because we are ourselves alive we are much more conscious of the processes of growth than we are of the processes involved in death and decay. This is perfectly natural and justifiable. Indeed, it is a very powerful instinct in us and a healthy one. Yet, if we are fully grown human beings, our education should have developed in our minds so much of knowledge and reflection as to enable us to grasp intelligently the vast role played in the universe by the processes making up the other or more hidden half of the Wheel. In this respect, however, our general education in the past has been gravely defective partly bcause science itself has so sadly misled us. Those branches of knowledge dealing with the vegetable and animal kingdoms—botany and zoology—have confined themselves almost entirely to a study of living things and have given little or no attention to what happens to these units of the universe when they die and to the way in which their waste products and remains affect the general environment on which both the plant and animal world depend. When science itself is unbalanced, how can we blame education for omitting in her teaching one of the things that really matter?

For though the phases which are preparatory to life are, as a rule, less obvious than the phases associated with the moment of birth and the periods of growth, they are not less important. If once we can grasp this and think in terms of ever-repeated advance and recession, recession and advance, we have a truer view of the universe than if we define death merely as an ending of what has been alive.

Nature herself is never satisfied except by an even balancing of her processes—growth and decay. It is precisely this even balancing which gives her unchallengeable stability. That stability is rock-like. Indeed, this figure of speech is a poor one, for the stability of Nature is far more permanent than anything we can call a rock—rocks being creations which themselves are subject to the great stream of dissolution and rebirth, seeing that they suffer from weathering and are formed again, that they can be changed into other substances and caught up in the grand process of living: they too, as we shall see (p. 85), are part of the Wheel of Life. However, we may at a first glance omit the changes which affect the inert masses of this planet, petrological and mineralogical: though very soon we shall realize how intimate is the connection even between these and what is, in the common parlance, alive. There is a direct bridge between things inorganic and things organic and this too is part of the Wheel.

But before we start on our examination of that part of the great process which now concerns us—namely, plant and animal life and the use man makes of them—there is one further idea which we must master. It is this: The stability of Nature is secured not only by means of a very even balancing of her Wheel, by a perfect timing, so to say, of her mechanisms, but also rests on a basis of enormous reserves. Nature is never a hand-to-mouth practitioner. She is often called lavish and wasteful, and at first sight one can be bewildered and astonished at the apparent waste and extravagance which accompany the carrying on of vegetable and animal existence. Yet a more exact examination shows her working with an assured background of accumulated reserves, which are stupendous and also essential. The least depletion in these reserves induces vast changes and not until she has built them up again does she resume the particular process on which she was engaged. A realization of this principle of reserves is thus a further necessary item in a wide view of natural law. Anyone who has recovered from a serious illness, during which the human body lives partly on its own reserves, will realize how Nature afterwards deals with such situations. During the period of convalescence the patient appears to make little progress till suddenly he resumes his old-time activities. During this waiting period the reserves used up during illness are being replenished.

THE LIFE OF THE PLANT

A survey of the Wheel of Nature will best start from that rather rapid series of processes which cause what we commonly call living matter to come into active existence; that is, in fact, from the point where life most obviously, to our eyes, begins. The section of the Wheel embracing these processes is studied in physiology from the Greek word φύσις, the root øύω meaning to bring to life, to grow.

But how does life begin on this planet? We can only say this: that the prime agency in carrying it on is sunlight, because it is the source of energy, and that the instrument for intercepting this energy and turning it to account is the green leaf.

This wonderful little example of Nature’s invention is a battery of intricate mechanisms. Each cell in the interior of a green leaf contains minute specks of a substance called chlorophyll and it is this chlorophyll which enables the plant to grow. Growth implies a continuous supply of nourishment. Now plants do not merely collect their food: they manufacture it before they can feed. In this they differ from animals and man, who search for what they can pass through their stomachs and alimentary systems, but cannot do more; if they are unable to find what is suitable to their natures and ready for them, they perish. A plant is, in a way, a more wonderful instrument. It is an actual food factory, making what it requires before it begins the processes of feeding and digestion. The chlorophyll in the green leaf, with its capacity for intercepting the energy of the sun, is the power unit that, so to say, runs the machine. The green leaf enables the plant to draw simple raw materials from diverse sources and to work them up into complex combinations.

Thus from the air it absorbs carbon-dioxide (a compound of two parts of oxygen to one of carbon), which is combined with more oxygen from the atmosphere and with other substances, both living and inert, drawn from the soil and from the water which permeates the soil. All these raw materials are then assimilated in the plant and made into food. They become organic compounds, i.e. compounds of carbon, classified conveniently into groups known as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats; together with an enormous volume of water (often over 90 per cent of the whole plant) and interspersed with small quantities of chemical salts which have not yet been converted into the organic phase, they make up the whole structure of the plant—root, stem, leaf, flower, and seed. This structure includes a big food reserve. The life principle, the nature of which evades us and in all probability always will, resides in the proteins looked at in the mass. These proteins carry on their work in a cellulose framework made up of cells protected by an outer integument and supported by a set of structures known as the vascular bundles, which also conduct the sap from the roots to the leaves and distribute the food manufactured there to the various centres of growth. The whole of the plant structures are kept turgid by means of water.

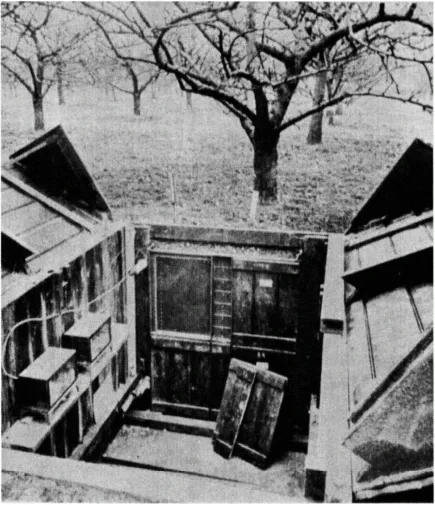

PLAIE I. OBSERVATION CHAMBER FOR ROOF SIUDIES

AT EAST MALLING

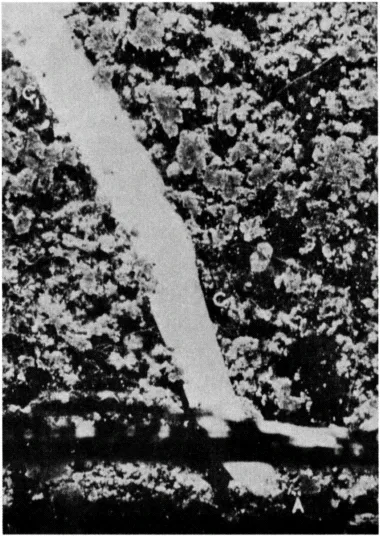

PLAIE II. THE BEGINNINGS OF MYGORRHIZAL

ASSOCIAT ION IN THE APPLE

Root-tip (x 12) of Lane’s Prince Albert on root-stock M XV7at sixteen inches below the surface, showing root-cap (A), young root hairs (C), and older root hairs with drops of exudate (Cj). The cobweb-like mycelial strands are well seen approaching the rootlet in the region marked (C).

The green leaf, with its chlorophyll battery, is therefore a perfectly adapted agency for continuing life. It is, speaking plainly, the only agency that can do this and is unique. Its efficiency is of supreme importance. Because animals, including man, feed eventually on green vegetation, either directly or through the bodies of other animals, it is our sole final source of nutriment. There is no alternative supply. Without sunlight and the capacity of the earth’s green carpet to intercept its energy for us, our industries, our trade, and our possessions would soon be useless. It follows therefore that everything on this planet must depend on the way mankind makes use of this green carpet, in other words on its efficiency.

The green leaf does not, however, work by itself. It is only a part of the plant. It is curious how easy it is to forget that normally we see only one-half of each flowering plant, shrub, or tree: the rest is buried in the ground. Yet the dying down of the visible growth of many plants in the winter, their quick reappearance in the spring, should teach us how essential and important a portion of all vegetation lives out of our sight; it is evident that the root system, buried in the ground, also holds the life of the plant in its grasp. It is therefore not surprising to find that leaves and roots work together, forming a partnership which must be put into fresh working order each season if the plant is to live and grow.

If the function of the green leaf armed with its chlorophyll is to manufacture the food the plant needs, the purpose of the roots is to obtain-the water and most of the raw materials required—the sap of the plant being the medium by which these raw materials (collected from the soil by the roots) are moved to the leaf. The work of the leaf we found to be intricate: that of the roots is not less so. What is surprising is to come upon two quite distinct ways in which the roots set about collecting the materials which it is their business to supply to the leaf; these two methods are carried on simultaneously. We can make a very shrewd guess at the master principle which has put the second method along-

side the first: it is again the principle of providing a reserve—this time of the vital proteins.

None of the materials that reach the green leaf by whatever method is food: it is only the raw stuff from which food can be manufactured. By the first method, which is the most obvious one, the root hairs search out and pass into the transpiration current of the plant dissolved substances which they find in the thin films of water spread between and around each particle of earth; this film is known as the soil solution. The substances dissolved in it include gases (mainly carbon dioxide and oxygen) and a series of other substances known as chemical salts like nitrates, compounds of potassium and phosphorus, and so forth, all obtained by the breaking down of organic matter or from the destruction of the mineral portions of the soil. In this breaking down of organic matter we see in operation the reverse of the building-up process which takes place in the leaf. Organic matter is continuously reverting to the inorganic state: it becomes mineralized: nitrates are one form of the outcome. It is the business of the root hairs to absorb these substances from the soil solution and to pass them into the sap, so that the new life-building process can start up again. In a soil in good heart the soil solution will be well supplied with these salts. Incidentally we may note that it has been the proved existence of these mineral chemical constituents in the soil which, since the time of Liebig, has focused attention on soil chemistry and has emphasized the passage of chemical food materials from soil to plant to the neglect of other considerations.

But the earth’s green carpet is not confined to its remarkable power of transforming the inert nitrates and mineral contents of the soil into an active organic phase: it is utilized by Nature to establish for itself, in addition, a direct connection, a kind of living bridge, between its own life and the living portion of the soil. This is the second method by which plants feed themselves. The importance of this process, physiological in nature and not merely chemical, cannot be over-emphasized and some description of it will now be attempted.

THE LIVING SOIL

The soil is, as a matter of fact, full of live organisms. It is essential to conceive of it as something pulsating with life, not as a dead or inert mass. There could be no greater misconception than to regard the earth as dead: a handful of soil is teeming with life. The living fungi, bacteria, and protozoa, invisibly present in the soil complex, are known as the soil population. This population of millions and millions of minute existences, quite invisible to our eyes of course, pursue their own lives. They come into being, grow, work, and die: they sometimes fight each other, win victories, or perish; for they are divided into groups and families fitted to exist under all sorts of conditions. The state of a soil will change with the victories won or the losses sustained; and in one or other soil, or at one or other moment, different groups will predominate.

This lively and exciting life of the soil is the first thing that sets in motion the great Wheel of Life. Not without truth have poets and priests paid worship to “Mother Earth,” the source of our being. What poetry or religion have vaguely celebrated, science has minutely examined, and very complete descriptions now exist of the character and nature of the soil population, the various species of which have been classified, labelled, and carefully observed. It is this life which is continually being passed into the plant.

The process can actually be followed under the microscope. Some of the individuals belonging to one of the most important groups in this mixed population—the soil fungi—can be seen functioning. If we arrange a vertical darkened glass window on the side of a deep pit in an orchard, it is not difficult to see with the help of a good lens or a low-power horizontal microscope (arranged to travel up and down a vertical fixed rod) some of these soil fungi at work. They are visible in the interstices of the soil as glistening white branching threads, reminiscent of cobwebs. In Dr. Rogers’s interesting experiments on the root systems of fruit trees at East Mailing Research Station, where this method of observing them was initiated and demonstrated to me, these fungous threads could be seen approaching the young apple roots in the absorbing region (just behind the advancing root tips) on which the root hairs are to be found. Dr. Rogers very kindly presented me with two excellent photographs—one showing the general arrangement of his observation chamber (Plate I), the other, taken on 6th July 1933, of a root tip (magnified by about twelve) of Lane’s Prince Albert (grafted on root stock XVI) at sixteen inches below the surface, showing abundant fungous strands running in the soil and coming into direct contact with the growing root (Plate II).

But this is only the beginning of the story. When a suitable section of one of these young apple roots, growing in fertile soil and bearing active root hairs, is examined, it will be found that these fine fungous threads actually invade the cells of the root, where they can easily be observed passing from one cell to another. But they do not remain there very long. After a time the apple roots absorb these threads. All stages of the actual digestion can be seen.

The significance of this process needs no argument. Here we have a simple arrangement on the part of Nature by which the soil material on which these fungi feed can be joined up, as it were, with the sap of the tree. These fungous threads are very rich in protein and may contain as much as 10 per cent of organic nitrogen; this protein is easily digested by the ferments (enzymes) in the cells of the root; the resulting nitrogen complexes, which are readily soluble, are then passed into the sap current and so into the green leaf. An easy passage, as it were, has been provided for food material to move from soil to plant in the form of proteins and their digestion products, which latter in due course reach the green leaf. The marriage of a fertile soil and the tree it nourishes is thus arranged. Science calls these fungous...