![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Cult of Relics

A relic is an object that was once connected with the body of a saint, martyr, or other holy person (see figure 1.1). In Christianity, veneration of relics appeared early in both Eastern and Western church practices (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1960, s.v. “Relics”).

The Origin of Relics

Early Christians believed that the bodies of the dead—or, by extension, objects that had touched them—had special qualities or powers that made them worthy of veneration. This was based on the concept of beneficent contagion:

Its basis is the idea that man’s virtue, or holiness, or protective healing powers, do not die with him; they continue to reside in his body and can be tapped by any believer who in some way makes contact with his corporeal shrine. Mere proximity is enough: the medieval pilgrim was satisfied if he could but gaze on the tomb of his cultobject….

If the body is dismembered, so the belief goes on, the power within it is not diminished; on the contrary, each part will be as full of potency as the whole. The same thing applies to anything that the cult object touched while alive or, indeed, to anything that touches him after he is dead. All these inanimate containers of a supposedly animate force—whole bodies, bones, hair and teeth, clothes, books, furniture, instruments of martyrdom, winding-sheets, coffins and (if the body is cremated) the ashes that are left—are dignified by the name of “relics” and credited with the grace that once resided in their owners. (Pick 1979, 101)

Figure 1.1. A portion of the vast collection of relics of saints kept in the Church of Maria Ausiliatrice in Turin, Italy (photo by Stefano Bagnasco).

The impulse to keep a relic may simply begin as an act of respect for a beloved person. For example, when Buddha died and was cremated, in about 483 B.C., his bones were reputedly saved by some Indian monks. Subsequently, a few pieces were taken to China, where a finger bone was discovered beneath a temple in 1987. In 2004, in what some saw as a “propaganda exercise,” China loaned the relic—displayed in a bulletproof glass container—to Hong Kong Buddhists for Buddha’s birthday celebration (Wong 2004). Primarily, however, the veneration of Buddha’s relics is intended to engender faith and acquire spiritual merit, although legends of miracles have sprung up (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1978, s.v. “Relics, Buddhist”).

The Old Testament makes specific reference to the veneration of relics. The religious character of a saintly person’s remains is acknowledged, for instance, in the burial of Rachel, the wife of Jacob: “And Rachel died, and was buried in the way of Ephrath, which is Bethlehem. And Jacob set a pillar upon her grave: that is the pillar of Rachel’s grave unto this day” (Genesis 35:19–20). There is also a reference to Joseph’s relics: “And Joseph took an oath of the children of Israel, saying God will surely visit you, and ye shall carry up my bones from hence. So Joseph died, being an hundred and ten years old: and they embalmed him, and he was put in a coffin in Egypt” (Genesis 50:25–26).

The Old Testament also refers to the miraculous power of a relic that was employed by Elisha:

He took up also the mantle of Elijah that fell from him, and went back, and stood by the bank of Jordan; and he took the mantle of Elijah that fell from him, and smote the waters, and said, “Where is the Lord God of Elijah?” And when he had also smitten the waters, they parted hither and thither: and Elisha went over.

And when the sons of the prophets which were to view at Jericho saw him, they said, “The spirit of Elijah doth rest on Elisha.” And they came to meet him, and bowed themselves to the ground before him. (2 Kings 2:13–15)

Like the mantle of Elijah, the relics of Elisha would come to work miracles, according to a later passage: “And it came to pass, as they were burying a man, that, behold, they spied a band of men; and they cast the man into the sepulchre of Elisha: and when the man was let down, and touched the bones of Elisha, he revived, and stood up on his feet” (2 Kings 13:21). This portrayal of Elisha as a potent magician—who could use the inherited mantle of Elijah to part Jordan’s waters and whose own bones could miraculously revive a dead man—sets the stage for the later miraculous relics of Jesus. This is not surprising, because in many ways, Jesus was seen as a successor to Elisha. For example, the story of Jesus’ miraculous multiplication of the loaves (Mark 6:34–44) follows a similar feat attributed to Elisha (2 Kings 4:42–44) (Metzger and Coogan 2001, 139).

The Veneration of Relics

Despite these Old Testament examples, there is little justification in either the Old or the New Testament to support what would become a cult of relics in early Christianity. Indeed, according to the New Catholic Encyclopedia (1967, s.v. “Relics”): “In the Apocalypse [or Revelation] the author recommends that the faithful and martyrs be left to rest in peace (11:13). Despite this, although the Apostles inherited Jewish diffidence regarding relics, the new converts in the time of St. Paul disputed about objects that belonged to the Apostles and recognized as miraculous agents clothing that they had touched (Acts 19:12).” This refers to Paul’s healing powers: “And God wrought special miracles by the hands of Paul: So that from his body were brought unto the sick handkerchiefs or aprons, and the diseases departed from them, and the evil spirits went out of them” (Acts 19:11–12).

The earliest veneration of Christian relics can be traced to around A.D. 156, when Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna (later St. Polycarp), was martyred. He was to be burned at the stake, but the fire blazed poorly, so he was stabbed to death instead. His body was then burned, after which his followers sought to take his remains. Although they encountered some resistance, they eventually “took up his bones, which are more valuable than precious stones and finer than refined gold, and laid them in a suitable place, where the Lord will permit us to gather ourselves together, as we are able, in gladness and joy, and to celebrate the birthday of his martyrdom” (Catholic Encyclopedia 1911, s.v. “Relics”; Coulson 1958, 383).

Figure 1.2. The focal point of the relic chapel in the Church of Maria Ausiliatrice in Turin is a lighted cross with a purported piece of the True Cross (photo by author).

Sometime after the death of St. Polycarp (exactly when is not known), the distribution and veneration of tiny fragments of bone, cloth, packets of dust, and the like became common. The practice was widespread in the early fourth century. Sometime before 350, pieces of wood allegedly from the True Cross, discovered circa 318, had been distributed throughout the Christian world (Catholic Encyclopedia 1911, s.v. “Relics”). (See figure 1.2.)

The early church fathers happily tolerated relic worship. As paganism retreated, according to historian Edward Gibbon (17371794):

It must be ingenuously confessed that the ministers of the Catholic Church imitated the profane models which they were impatient to destroy. The most respectable bishops had persuaded themselves that the ignorant rustics would more cheerfully renounce the superstitions of paganism, if they found some resemblance, some compensation in the bosom of Christianity. The religion of Constantine achieved, in less than a century, the final conquest of the Roman Empire: but the victors themselves were insensibly subdued by the arts of their vanquished rivals. (quoted in Meyer 1971, 73)

No less a figure than St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) set forth the doctrinal principles on which relic veneration is based:

It is clear … that he who has a certain affection for anyone, venerates whatever of his is left after death, not only his body and the parts thereof, but even external things, such as his clothes and such-like. Now it is manifest that we should show honour to the saints of God, as being members of Christ, and children and friends of God, and our intercessors. Wherefore in memory of them we ought to honour any relics of theirs in a fitting manner: principally their bodies, which were temples, and organs of the Holy Spirit dwelling and operating in them, and are destined to be likened to the body of Christ by the glory of the resurrection. Hence God Himself fittingly honours such relics by working miracles at their presence. (Aquinas 1273)

From a modern scientific point of view, such an attribute is rooted in superstition—an explanation of both its appeal (to the emotional rather than the rational) and its potential for abuse.

The Dispensation of Relics

In the fourth and fifth centuries, the veneration of the relics of martyrs expanded in the form of a liturgical cult, receiving theological justification. Martyrs’ tombs were opened, and relics were subsequently distributed as brandea—objects that had been touched to the body or bones. These were placed in little cases that were worn around the neck (New Catholic Encyclopedia 1967, s.v. “Relics”).

Christian saints’ relics are divided into four classes:

1. A first-class relic is either the body of a saint or a portion of it, such as a piece of bone or fragment of flesh.

2. A second-class relic is an item or piece of an item that was used by a saint, such as an article of clothing.

3. A third-class relic is an item that was deliberately touched to a first-class relic.

4. A fourth-class relic is anything that was deliberately touched to a second-class relic with the intent of creating a fourth-class relic.

First- and second-class relics were especially revered, whereas third- and fourth-class relics could be given away or sold to individuals.

Relics provided a concise link between tombs and altars. As the saints’ tombs became pilgrimage sites, churches were erected there to enshrine the relics and promote devotion to the local saints. An example is the Vatican’s Basilica of St. Peter, which was built over the apostle’s reputed grave (Woodward 1990, 57).

In the year 410, the Council of Carthage ordered local bishops to destroy any altar that had been set up as a memorial to a martyr and to prohibit the building of any new shrine unless it contained a relic or was built on a site made holy by the person’s life or death (Woodward 1990, 59). By 767, the cult of saints had become entrenched, and the Council of Nicaea declared that all church altars must contain an altar stone that held a saint’s relics. To this day, the Catholic Church’s Code of Canon Law defines an altar as a “tomb containing the relics of a saint” (Woodward 1990, 59). The practice of placing a relic in each church altar continued until 1969 (Christian relics 2004).

Acquisition of an important relic could justify the building of an elegant repository in which to house it. For instance, when the residents of Amiens acquired a piece of John the Baptist’s head in 1206, they resolved to erect France’s largest church. By 1220, they had gathered the necessary resources, and “the noble vault of the cathedral was steadily rising” (Tuchman 1978, 12).

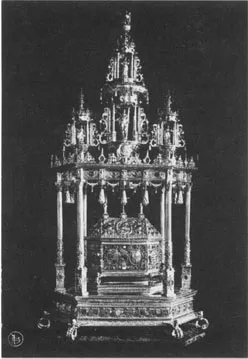

The practice of placing relics on exhibition was authorized during the ninth century, but not until the thirteenth century were reliquaries—containers used to keep or display relics—placed permanently on (or more often behind) the altar (Catholic Encyclopedia 1907, s.v.“Altar”). Reliquaries appear in an impressive variety of forms, including boxes, caskets, shrines, and the like, and they are typically ornate, often made of silver or gold and commonly bejeweled (see figure 1.3). For example, a French casket of the twelfth or thirteenth century depicts a crucified Christ and other holy personages in Limoges enamel on copper, studded with gems. Another reliquary contains the Holy Thorn set in a gemstone and surrounded by an enameled scene of the Last Judgment, with many figures in full relief and bearing the arms of John, duke of Berry (circa 1389–1407). A Venetian glass reliquary, stemmed like a goblet and surmounted with a glass cover, dates from the late sixteenth century. (See Encyclopaedia Britannica 1960, s.v. “Romanesque Art,” “Enamel,” “Glass.”) In the fourteenth century, King Charles V of France collected incredible relics that he kept in gem-studded reliquaries in his royal chapel. These included a fragment of Moses’ rod, a flask containing the Virgin’s milk, Jesus’ swaddling clothes, and other alleged relics, including many related to the Crucifixion (Tuchman 1978, 237).

One type of reliquary, known as a monstrance, typically consisted of a metal-framed, cylindrical crystal case mounted on a stand. It was originally used to expose sacred relics to view, but over time, it became the vessel in which the Host, or consecrated wafer, is carried in processions for veneration by the faithful (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1960, s.v. “Monstrance”). Another distinct type of reliquary took the shape of a forearm and a hand, mounted upright on a base. These hand reliquaries had small glass windows, typically located on the ornately fashioned “sleeve,” that held bits of bone or other relics. Some featured two fingers upraised in the familiar gesture of benediction; these usually represented a bishop or abbot-saint, “since they retained their earthly status along with their healing powers after death” (Piece of the week 2001). Other reliquaries took the form of a leg or a bust. In Naples Cathedral, for example, is a silver bust of St. Januarius that reputedly holds the legendary martyr’s skull (Rogo 1982, 192).

Relic veneration continues within Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, but it was rejected by the Protestant Reformation and by most of today’s Protestants (Christian relics 2004). With the closure of Latin monasteries and convents in 1962, and as relic holders, such as priests, have died, relics have found their way onto the open market. An organization has been formed to reclaim them. Called Christian Relic Rescue (CRR), it was founded in 2002 and “obtains (usually through purchase) as many First and Second Class Relics of Christian Saints as possible from auctioneers, antique dealers, and unauthorized individuals for the purpose of placing the Relics at no cost, in Faith Communities where they receive the Christian veneration for which they were intended” (Relics in Christian faith 2005).

Figure 1.3. Ornate reliquary of the reputed blood of Christ is displayed in a basilica in Bruges, Belgium (from an old postcard).

Authentication

The sale of relics had become so prevalent in the time of St. Augustine (about 400) th...