![]() Part 1: Introductory Thoughts

Part 1: Introductory Thoughts![]()

1 A Broad Introduction to Social Research

Doing Research and Reading Research

Doing research which involves people – or ‘social research’ – can be very enjoyable. Travelling around, meeting different people, encountering different organizations such as schools or businesses, hearing new accents, meeting employers, seeing ‘how the other half live’ are all part of the fun.

Doing ‘people research’ can involve an almost infinite range of activities: asking people questions; listening and observing; administering performance tests; evaluating resources, schemes, programmes or teaching methods; performing brain scans and monitoring physiological responses (changes in heart rate, blood pressure or dilation of pupils) in response to various stimuli.

Research rarely goes according to plan – it can be messy, frustrating and unpredictable, and we discuss this in our book: conducting focus groups in which only one person turns up; arranging to meet a group of apprentices 90 miles away and arriving to find that their ‘mentor’ had mistakenly sent them home; visiting a school to find it closed for a ‘Baker Day’; arranging to interview a ‘very busy’ employer for half an hour who in the event talks for two hours; a child refusing to complete your carefully constructed test, which she calls ‘boring’ (while her other classmate calls it ‘trivial’). All these things have happened to us.

These are the differences between social research, which deals with humans, their society and culture and their organizations, and research in physics, which deals with inanimate, idealized entities such as point masses, rigid bodies and frictionless surfaces.

These differences also imply a different code of conduct in contrast to the physical sciences, simply because social research involves the study of human beings. The physical sciences do have their own canons and ethics, but social research has additional ethical demands. Concern for ethics should start at the outset of any research project and continue through to the write-up and dissemination stages. Morals and ethics in research are considered at different times in this book.

As well as considering how people ‘do’ research we also look at how one might ‘read’ research. By what standards should we judge the research we read about? How can we distinguish good research from bad, assuming that it is more than simply a matter of taste? Are the conclusions drawn justified from the evidence or data collected? These are issues that we will consider, not least in the vignettes that are included in this book.

Research in the Media

For most people who are not researchers, their most common encounter with research is in the media. Research, of course, is constantly in the media. Research involving human beings, like politics or the selection of the national rugby, tennis or soccer team, is a subject on which everyone feels they are an expert, simply because we are all humans.

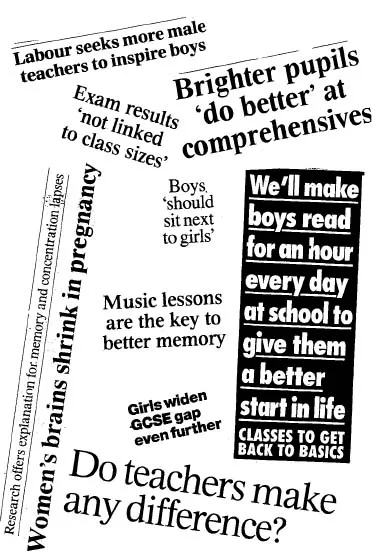

The collage of newspaper cuttings in Figure 1.1 shows some of the old chestnuts which have been media favourites for decades (see Baker, 1994). Some of the other questions and headline statements from social and medical research that have caused considerable media activity are:

• Can MMR cause autism?

• Do teachers make any difference?

• Regular exercise can ward off dementia.

• Drinking wine is good for your heart.

• Inequality in society causes crime.

• Infants are better off if they stay with their mothers.

A more recent controversial topic has been the underachievement of boys, which received a huge volume of newspaper coverage in early-1998 and has recurred regularly since (incidentally, one wonders if the media spotlight would have been as strong if girls’ GCSE results had fallen significantly below boys’).

Figure 1.1 Research in the Media

As well as the usual suspects, the occasional zany or off-the-wall item of research makes headlines. For example, the observation that ‘women’s brains shrink during pregnancy’ was first put forward in 1997 and said by certain newspapers to be based on new scientific evidence. In 1998, music lessons were reported for the first time to be the ‘key to a better memory’ – based on a ‘controlled’ experiment in Hong Kong with 30 female students who had received them and 30 who had not. This topic of research continued to attract wide newspaper interest, with (for example) a Times article in 2006 (20 September, page 9) reporting an experimental study with only 12 children, displaying the headline ‘Why music lessons are good for the memory’. Perhaps, we would speculate, these studies received media interest because they involved a controlled experiment which was perceived to have higher or ‘scientific’ status. As it turned out, the initial findings of the beneficial effects of classical music on memory and learning were not replicated. While the media hype beyond this so-called ‘Mozart effect’ does return occasionally it is fuelled by little evidence – as is much of the media hype about research, generally speaking. This is perhaps inevitable: the media goes for novelty, while establishing scientific consensus takes a great deal of systematic, unglamorous replication and follow-up.

Indeed, a systematic research programme which carried out an in-depth study of current media selection, filtering and portrayal of social research would make an interesting study. It might well reveal a media bias towards research which is seen as ‘scientific’, objective and value-free and against studies which are qualitative and therefore deemed to be value-laden and subjective – but this is speculation.

A Brief History of Social Research: Recurrent Debates

We cannot give a detailed account of the history of social research here but we can trace some of the key features and past definitions which have shaped its history. This brief history will help to highlight some of the recurring debates about research and research methods.

From the Laboratory Approach to the ‘Natural’ Setting

The location of social research has gradually shifted from the laboratory or the clinic to the real-life or ‘natural’ context. For example, one of the hot topics at the end of the nineteenth century was the study of ‘individual differences’ between human beings, most notably with the work of Galton, which was largely laboratory based and dependent on the statistical techniques of that era; this is an area which was to return in 1973 with Arthur Jensen and many other players in this large and diverse field (discussed further in Chapter 8).

Similarly, Thorndike’s work in the first quarter of the last century is often noted as a key influence in the years to come. His famous slogan ‘whatever exists at all exists in some amount’ (Thorndike, 1918, p. 16) inspired and influenced subsequent researchers to mimic the ‘scientific method’ and rely exclusively on quantitative methods. His work on testing and academic achievement was very much laboratory research, divorced from the messy reality of homes, schools and classrooms.

Despite his apparent obsession with the quantitative and distance from a natural setting such as a home or the classroom, Thorndike’s work in one area remains a live issue. He argued that training (or learning) in one situation would not readily transfer to another situation or context. His scepticism over ‘transfer of training’ is ironic in that his own conclusions on the difficulty of transfer have been extended and generalized from the clean, clinical world of laboratory to the complex, unpredictable worlds of school education and youth training. Nowadays, the transfer debate is as live as ever but is studied in natural settings, i.e. in context, rather than in labs. The transfer debate reappeared prominently in the 1970s with the emergence of ‘generic’ or ‘transferable’ skills in both schooling and youth training based on the belief that they would make young people more employable Skills of a similar nature were given further prominence by the ‘core skills’ movement in the 1980s and their rechristening as ‘key skills’ at the end of the last century. Thorndike’s original scepticism about ‘transfer’ reappeared with the ‘situated cognition’ movement of the last era which argued persuasively that skill, knowledge and understanding is context dependent, i.e. ‘situated’. All of this work focused on skills development in real-life contexts such as apprenticeships and the workplace (see Lave’s 1986 work on cognition in practice, and many other books). A similar impulse led to the calls for the ‘ecological validity’ (i.e. real-life relevance) of psychological research.

Ethics, from Jenner to Burt

Debates on social issues or problems, and arguments over how they should be researched, have a habit of recurring. Debates on the code of conduct governing research form one perennial example, though we do seem to have made some moral progress. In 1796, a doctor called Edward Jenner borrowed an 8 year-old Gloucestershire schoolboy named James Phipps and infected him with cowpox. Jenner later infected him with smallpox and (fortunately) James recovered. This ‘scientific’ experiment (incidentally with a sample of one) led eventually to widespread vaccination.

Similar examples have occurred in social research. In the two examples cited briefly below, one involves unethical methods and the second unethical analysis of data:

• The first, like Jenner’s in employing unethical methods, was reported by Dennis in 1941. He was involved in the raising of two twins in virtual isolation for a year in order to investigate infant development under conditions of ‘minimum social stimulation’ (Dennis, 1941).

• A better-known name, Cyril Burt, who is renowned for his testing of ‘intelligence’ and the assessment of ability, has been accused of twisting, manipulating and even fraudulently misrepresenting his data (see Flynn, 1980), and probably also fabricating them, though that is controversial (see Joynson, 1989).

Ethical issues are a common feature in the history of both scientific and social research.

The ‘Jump’ from Data to Theory

Approaches to research have changed and we consider the possibilities now available in a later chapter. One issue that has not changed is the connection between a researcher’s ideas and theories and the data they have collected. In some ways this is still a mystery, mainly because it seems to rely on some sort of ‘creativity’, act of faith or blind leap from data to conclusions in certain cases.

Are the ideas directly derived from their research data by some sort of process of induction? Or do they stem from creative insights, hunches and imaginative thinking? Probably a combination of both, one would suspect. These questions are revisited later when we discuss the meaning and place of ‘theory’ in social research.

There are many other valuable ideas in the history of social research where it is unclear whether they are inferences from the research data, guiding a priori hypotheses, imaginative insights, or creative models for viewing the social world. One is Gardner’s idea of multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1993), which argues that intelligence has many different facets. Gardner went further than other psychologists by claiming that there is not a single thing called intelligence, but a set of as many as eight distinct sets of abilities (multiple intelligences). Guilford’s (1967) model of the human intellect, which distinguishes between ‘divergent’ and ‘convergent’ thinking is another example. It is not clear whether these models of the human mind are based on speculation or on evidence – and this is true of other theories in social science.

The purpose of this brief history, with its limited range of examples, has been to show that none of the major issues discussed in this book are new. The following debates or questions all have a past and will all have a future:

• the relation to, and impact of, research on practice;

• the difference between research in an experimental or a laboratory setting and investigations of naturally occurring situations;

• the range of foundation disciplines which have and have not related (and should or should not relate) to social research: philosophy, biology, history, sociology, psychology, anthropology;

• the importance of ethics in conducting research and analysing the data;

• the nature and role of theory in research and the mystery of where theories come from (we know they come from pe...