![]()

1

The empire of Christ

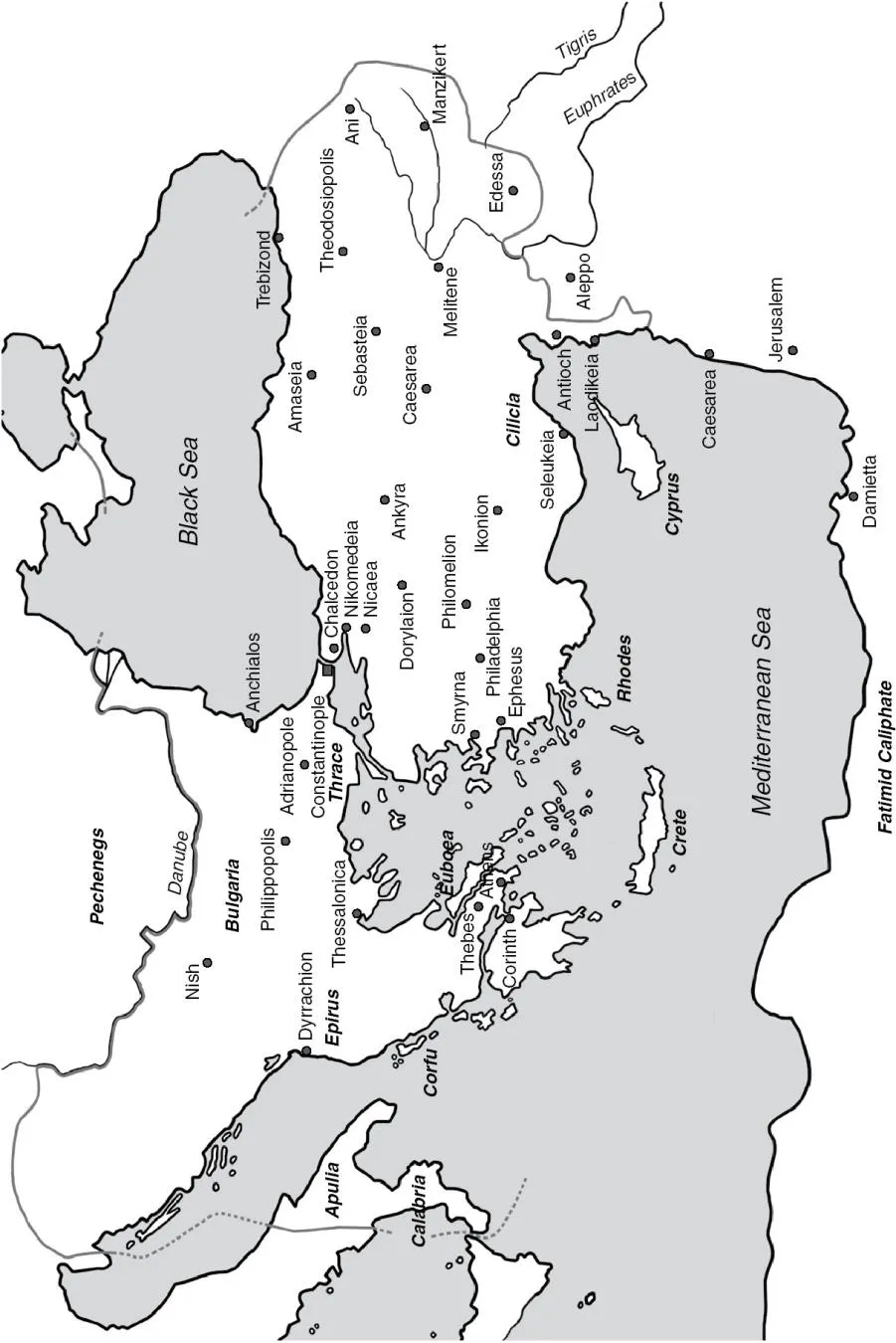

In about the year 1050, the Byzantine empire, known also as ‘Byzantium’, was the largest and most prosperous political entity in the Christian world. On its eastern side, it consisted of Asia Minor or Anatolia, that is to say what is now Turkey, and part of Armenia along with the island of Cyprus. In the west it covered Greece and the Balkans south of the Danube, the Aegean and Ionian islands, and Crete. The empire also retained a few isolated outposts across the Black Sea in the Crimea, most notably the city of Cherson, and part of southern Italy, the provinces of Calabria and Apulia. These borders were the result of a considerable expansion which had taken place over the previous hundred years, especially during the reigns of the emperors Nikephoros II Phokas (963–9), John I Tzimiskes (969–76) and Basil II (976–1025). In the east, the Byzantines had taken advantage of the increasing weakness of their traditional Muslim enemy, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. Crete had been taken from the Arabs in 961 and Cyprus in 965. In the autumn of 969, the great city of Antioch, which had been under Arab rule for over 300 years, opened its gates to a Byzantine army, and Edessa was captured in 1031.1 Further to the east, the Christian rulers of Armenia had been persuaded one by one to yield their territories to the emperor in Constantinople, culminating in the Byzantine annexation of Ani in 1045. The empire had also extended its borders on its western side as it settled old scores with its long-time rival, Bulgaria. In 1018, after many years of intense warfare, Basil II had completed the conquest of the country and incorporated it into the empire. There were plans for further expansion. An expedition to Sicily in 1038 had occupied the eastern side of the island but this foothold was lost within a few years.

One consequence of Byzantine military success was that, especially after 1018, many parts of the empire enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity as the threat of foreign invasion, ever present in previous centuries, now diminished. The frontier districts, particularly newly incorporated Bulgaria, Syria and Armenia, remained vulnerable to raids from neighbouring nomads, so many urban centres such as Adrianople, Philippopolis, Antioch and Theodosiopolis retained their military function and garrisons.2 In the interior provinces, on the other hand, particularly in what is now Greece and western Turkey, towns were flourishing as centres of industry and commerce. Archaeological excavations reveal that areas of Corinth and Athens, which had been deserted for centuries, had now been reoccupied and built over, and important industries had begun to grow up. Corinth produced textiles, cotton, linen and silk, as well as possessing an important glass factory. Athens concentrated on dyes and soap. Thebes was renowned for its high-quality silks, prized above all others for the quality of their workmanship. Thessalonica, the second city of the empire, hosted an annual fair which attracted merchants from all parts of the Mediterranean world, as well as being a centre for the production of silk and metalwork.3 In Asia Minor, wealth lay in agriculture rather than in commerce or manufactures, as peaceful conditions allowed more land to be brought back under cultivation. Here too there were signs of expansion and renewal in the towns. Ikonion, on the flat Anatolian plain, flourished as a market town and Philadelphia, in the fertile lands of western Asia Minor was described by a contemporary as a ‘great and prosperous city’. In the north-west, the chief regional centre was Nicaea, of historic importance as the site of two ecumenical councils of the Church in 325 and 787, but also a staging post on the road east, and a market for agricultural produce and fish from its lake. The new-found wealth of the provinces is reflected in the rich mosaics and interior decoration of the monasteries of Daphni near Athens and Hosios Loukas in Central Greece which bear witness to the availability of wealthy patrons and their readiness to make pious donations.4

MAP 1 The Byzantine empire, c.1050.

In general therefore Byzantium was probably a more prosperous and settled society in the mid-eleventh century than the fragmented and localized countries of western Europe. The contrast should not be overstressed. Modern maps showing the empire with wide borders fail to take into account that central authority was not uniform over the whole area. The further one went from the capital, the more power was devolved into local hands. The aristocracy or archons of eastern Asia Minor or the western Balkans enjoyed a great deal of independence, often leading their own armies into battle. On the frontier district local rulers were often allowed to remain in charge provided that they acknowledged the authority of the Byzantine emperor.5 These everyday realities aside, Byzantium was set apart from other Christian states in the eyes of contemporaries by having a fixed capital city and centre of government. This was Constantinople, the modern Istanbul, strategically situated at the crossing between the empire’s European and Asiatic provinces, and founded in the year 330 by the emperor Constantine I (306–37) on the site of an earlier city named Byzantion. The Byzantines themselves took enormous pride in it: so important a place was it in their eyes that they seldom needed to refer to it by name, preferring to use epithets such as the ‘Queen of Cities’, the ‘Great City’ or just ‘the City’.6 This was not mere local patriotism for foreign visitors to Constantinople were equally extravagant in their praise. A French priest who arrived with the First Crusade in 1097, gushed enthusiastically about the ‘excellent and beautiful city’ and an Arab visitor recorded that the place was even better than its reputation. A Jewish physician marvelled at the ‘countless buildings’. To the Scandinavians, it was known as Micklagard, the great city, and among the Russians as Tsargrad, the imperial city.7

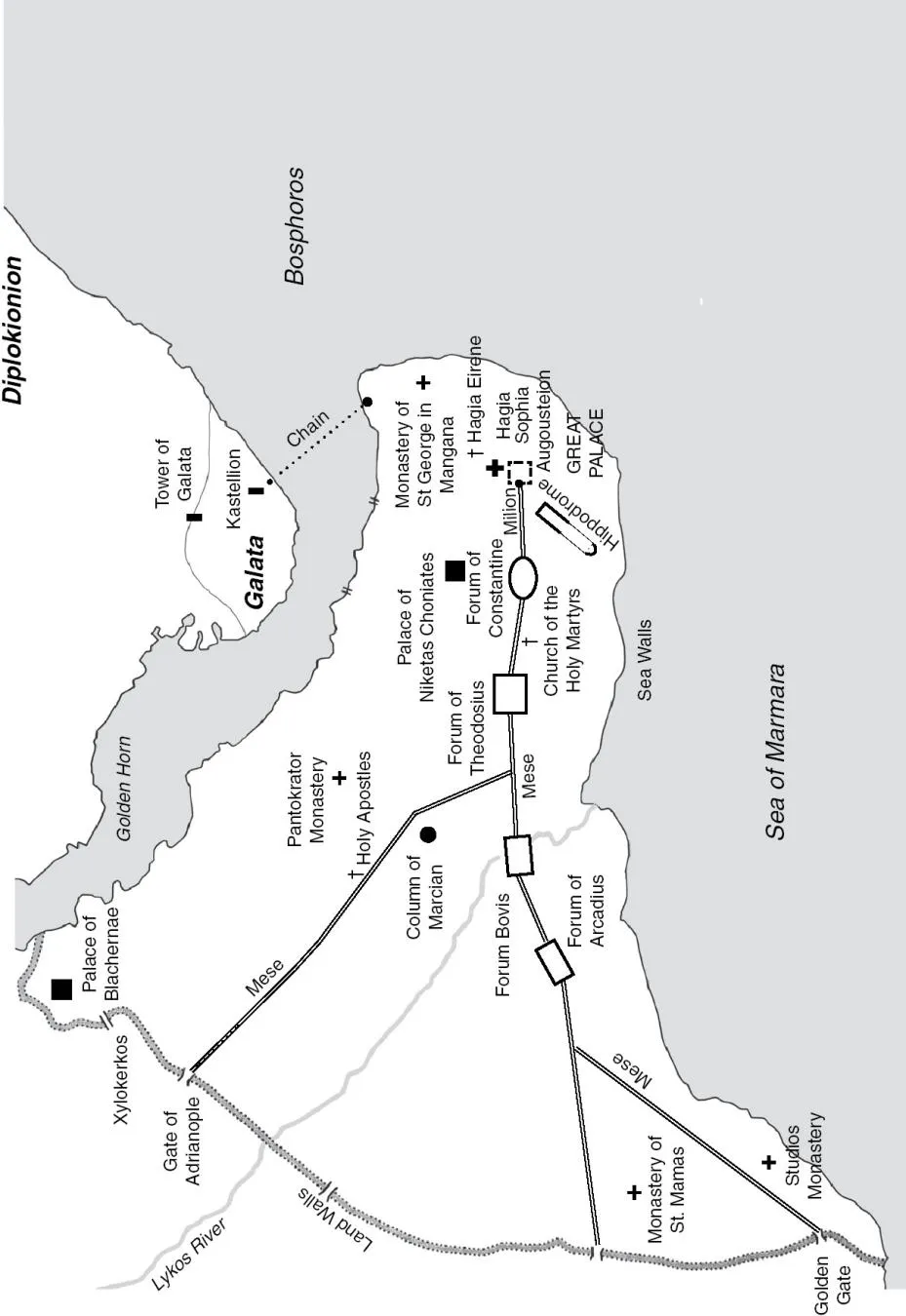

There were a number of reasons for the pride which Constantinople inspired on the part of its citizens, and the awe and astonishment it provoked from outsiders. One was its impregnability. It enjoyed a natural defensive position, placed on a narrow promontory that was bounded by water on two sides, the Golden Horn and the Bosporus to the north and the Sea of Marmara to the south. On the landward side, previous emperors had constructed a colossal, fortified wall stretching from the Golden Horn to the Sea of Marmara, about nine metres high and four and a half metres thick. It was punctuated at intervals by 96 towers, providing broad platforms for archers and catapults. In front of the walls was a wide ditch, which any assailant had to cross while exposed to withering fire from the walls. The fortifications continued along the seaward sides, making assault by sea equally daunting.8 Thanks to these defences, Constantinople had withstood numerous sieges over the centuries. One of the most serious had been mounted by the Persians and Avars in 626, when they had blockaded the city simultaneously from east and west. The Arabs had tried for four years between 674 and 678, with the support of a powerful fleet. Both sieges had to be broken off in the face of the unyielding defences. In later years, the Russians and the Bulgars were also to make the attempt, with similar lack of success. After the last Russian attack, a naval assault in 1043, some 15,000 enemy corpses were counted, washed up on the shores of the Bosporus. The towering defences of Constantinople were the first thing a visitor would have seen when arriving by land or sea. The French cleric Odo of Deuil, who travelled with the Second Crusade in 1147 and who had little good to say about the Byzantines, poured scorn on the walls, claiming that they were in poor repair. The soldiers of the Fourth Crusade, however, shuddered when they saw them.9

The second aspect of Constantinople that marked it out was its size, for by medieval standards it was an enormous city and certainly the largest in the Christian world. Rome, which had once been so vast and powerful, had declined by the eleventh century to a shadow of its former self, with large areas within its walls desolate or uninhabited. London had not yet begun to grow and on the eve of the Norman invasion of 1066 probably had a population of no more than 12,000. Constantinople, by contrast, is believed to have had at least 375,000 inhabitants, making it more 30 times the size of London, and it was estimated at the time that more people lived within its walls than in the whole of the kingdom of England south of the Humber.10 The closest cities of comparable size were to be found in the Islamic world. Cordoba in Spain was probably roughly the same size, while Baghdad was considerably larger. Like many large cities today, Constantinople’s population was multiracial, reflecting both the ethnic composition of the empire as a whole and the world around it. While the majority was composed of Greek-speakers, there were large numbers of Armenians, Russians and Georgians. There was a sizeable Jewish community, concentrated mainly in the suburb of Galata on the other side of the Golden Horn, Italian merchants from the trading cities of Venice, Genoa and Pisa, and mercenaries from western Europe and Scandinavia. There was even a small Arab community in Constantinople, mostly merchants, for whose use a mosque was provided. That pattern was repeated in other parts of the empire. While Greek was its official language, Armenian and Slavonic languages were also widely spoken, especially in the frontier districts. There were also pockets of Slavs in Asia Minor, and of Armenians in the Balkans, as a result of the policy of forced resettlement pursued by the emperors over the centuries.11

MAP 2 The city of Constantinople.

FIGURE 1 The Land Walls of Constantinople, as recently restored, showing the outer and inner walls, some of the 96 defensive towers and the site of the moat, now occupied by vegetable plots. (Vlacheslav Lopatin/Shutterstock.com)

Another aspect of Constantinople frequently commented on by natives and visitors alike was its wealth. It was the boast of Constantinople’s citizens that two-thirds of the riches of the world were concentrated in their city, and newcomers were astonished by the sheer opulence that they saw around them, especially the abundance of gold, silver and silk.12 Part of this was generated by manufacturing for Constantinople was famous for its metalwork. The city’s gold and silversmiths had their own area around the main square, the Augousteion, and much of their work was exported, particularly to Italy. Other industries based in the imperial capital were silk dressing and dyeing, manufacture of silk garments, and soap, perfume and candle making. Banking and money lending also flourished, though they were strictly regulated.13 The main reason for Constantinople’s wealth, however, was trade. Thanks to its geographical position between Europe and Asia, Constantinople was an obvious entrepôt where goods from one part of the world could be exchanged for those of another. Merchants gathered in the commercial quarter, along the Golden Horn. The Arabs brought spices, porcelain and jewels, the Italians tin and wool, the Russians wax, amber, honey and fur. These were then sold on or exchanged for products to ship back to their home markets. Although much of this activity was in the hands of foreign merchants, the Byzantine authorities benefited by charging a customs duty, the Kommerkion, of 10 per cent on all imports and exports, and the city as a whole grew rich on the commercial opportunities presented by the influx of merchants, goods and raw materials.14

The prosperity of Constantinople was most visible in its buildings, whether public, private or ecclesiastical. It was unusual among medieval cities in being a deliberately planned city, rather than a random jumble of buildings, with space set aside for public events and ceremonies. Most of this space was concentrated at the eastern end, but it was linked to the walls in the west by the long main street known as the Mese. The Mese began at the far south of the Land Walls, at the Golden Gate, an imposing entrance surmounted by four large bronze elephants, which was traditionally used to enter the city by emperors returning from a successful campaign.15 From there the Mese ran east through a series of public squares before terminating at the Augousteion, which was dominated by the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and by a huge bronze equestrian statue of the emperor Justinian (527–65). The figure of the emperor faced east, holding in one hand an orb surmounted by a cross, his other raised in warning to his enemies.16

FIGURE 2 The cathedral of Hagia Sophia as it is today, with minarets dating from after the Turkish conquest in 1453. (Saida Shigapova/Shutterstock.com)

To the south of the Augousteion stood the 400 metre long Hippodrome, which could seat up to 100,000 people. It had originally been designed for the staging of chariot races which a central spine, around which the contestants would career at high speed. The spine was decorated with ancient statues and sculptures brought as trophies by earlier emperors from all over the Mediterranean world, a rich profusion that served no other purpose other than adornment.17 By the ele...