![]()

PART I

CAPTIVES

BY the 1740s, merchants and slave traders along the Biafran littoral and their connections in the interior succeeded in consolidating long-existing trade networks while aggressively forging new ones. In the resulting commercial transformation, the trading men and women of Bonny and Elem Kalabari (also known as New Calabar) in the eastern Niger Delta and Old Calabar in the Cross River began funneling more captives toward the Americas than at any other time in the region’s history. By the second half of the eighteenth century, traffic from these three Biafran towns accounted for a greater share of Great Britain’s total transatlantic traffic in slaves than any other three ports in western Africa.1

Each of these seaports was remarkable in its own right. Bonny may have been established as a trading town as early as 1500. In Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, a sixteenth-century summary of Portuguese maritime knowledge, Duarte Pereira described a bustling town of some two thousand inhabitants at the mouth of the Rio Real that may have been one of Bonny’s early incarnations. Enormous trading canoes, some large enough to ferry eighty men, piloted the waterways surrounding the settlement, facilitating a brisk up-river trade in salt, yams, cows, goats, and sheep. In addition to this trade in foodstuffs and livestock, a vigorous market in slaves was carried on as well.2

The Bonny of the late 1700s, though its economy and society had no doubt changed dramatically since first visited by Portuguese caravels, could still be described commercially in much the same language as used by Pereira. At the end of the eighteenth century, the town consisted of a “considerable number” of small houses framed with supporting poles and covered with mats—the whole plastered together with the red earth of the eastern delta. Most were built close to the river, so water frequently washed their foundations, turning the surrounding ground into a swampy morass.

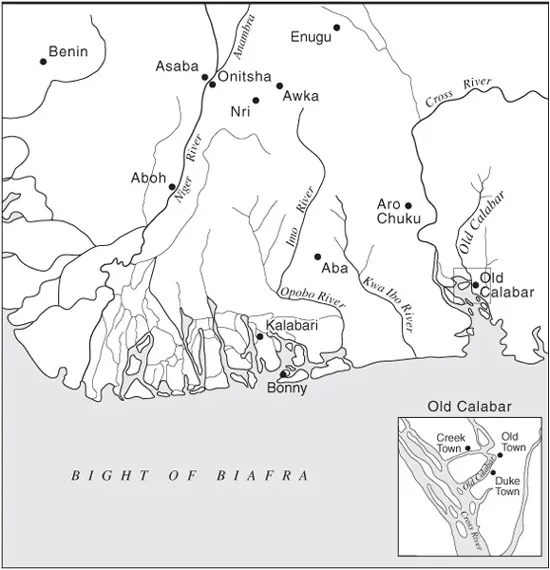

Figure 2. Bight of Biafra and Biafran interior

Source: Map drawn by the Cartographic Laboratory, Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin

As many as fifteen Guineamen might anchor off Bonny at a time—some ships beginning, others ending, and a number in the middle of the tedious business of taking in slaves. Telltale signs of the town’s integration into the Atlantic and upriver trades were evident throughout the community: Bonny’s cityscape was shot through here and there with the trading complexes, warehouses, and canoe landings of trade-rich aristocrats, merchants, and their retinues. Evidence of the town’s peculiar commercial orientation even carried through the very air of the place: now and again the murmuring of merchants, traders, and slaves, the calls of livestock and wildlife, and the sounds of the river itself were drowned out by the cannon of slave ships announcing their coming or going, or by the fanfare of canoe traders who burst into song and music, and hoisted their colors before paddling to upstream markets to trade for slaves. And over the whole place hung a pall of death: The stench of rotting bodies emanated from the burial grounds of European seamen who had expired while waiting for slaves and were interred in shallow graves opposite the town proper.3

Behind Bonny, accessible from the Rio Real estuary, lay the trading town of Elem Kalabari—referred to by Europeans as New Calabar. In the seventeenth century, the settlement was described by British slave trader James Barbot as being very similar to Bonny, its larger neighbor farther toward the coast. “The town,” wrote Barbot, “is seated in a marshy island often overflow’d by the river, the water running even between the houses, where there are about three hundred in a disorderly heap.” In 1699, Barbot’s trading voyage to the eastern delta consisted, in the main, of sailing back and forth between Bonny and New Calabar gathering nearly six hundred slaves for the three hundred-ton frigate Albion.4

Decades later, at the height of the Atlantic slave trade, the place of trade slaves in the town’s economy had expanded significantly, but the general processes remained the same as when Barbot had sailed there three generations earlier. British traders to the eastern delta still ran between Bonny and New Calabar drawing slaves from canoe traders who had in turn transported them in parcels from upriver markets. Only, by the late eighteenth century New Calabar was almost wholly oriented toward the sea. The Atlantic and its trade mattered there to more people and for more reasons than it ever had before.5

The third major eighteenth-century slaving port in the Bight of Biafra was not in the Niger Delta proper, but farther east in the estuary of the Cross River. Old Calabar lay about thirty miles up the river and was really three settlements founded one after the other during the early seventeenth century: Creek Town, Old Town, and Duke Town. Anachronistically, Old Calabar was much younger than New Calabar (and Bonny as well for that matter), and in all likelihood did not develop into a regional Atlantic entrepôt until the mid-1700s. Still, as early as 1668 there was enough general knowledge among Europeans about the towns that the English sailor John Watts, in a fictionalized account of his ordeal in the Cross River, assumed that his audience had already heard a great deal about the geography and folkways of the area. In discussing the people, landscape, trade, and manners of Old Calabar and environs, Watts admitted that the information he would offer on those heads was “no more than others have spoken formerly, who have been in the same Country.”6

In the late eighteenth century, however, it is clear from the descriptions offered by British slave traders that Old Calabar was different from its counterparts farther west. British mariners painted New Calabar and Bonny as water-logged trading towns given over almost entirely to the Atlantic trade in slaves.7 The approach to Old Calabar, in contrast, betrayed a diversified economy. “The Banks of the rivers, till you come near the Towns, are covered with Mangrove Woods,” reported one British captain, but nearer to the settlements themselves, “the Land is cultivated, and produces Rice and Guinea Corn; and there appeared to be a great Quantity of Cattle.” In a travelogue of the west African coast, the Briton John Adams added that Old Calabar exported a significant quantity of palm oil and barwood in addition to participating in the lucrative trade in human beings. To distinguish the town further from its neighbors, Adams added, “Many of the natives write English, an art first acquired by some of the traders’ sons, who had visited England, and which they have had the sagacity to retain up to the present period.”8

The journal of one such African trader, recounting the death of a town oligarch named Edem Ekpo, provides a telling glimpse of Old Calabar and of some of its most unfortunate inhabitants, its slaves.9 Old Calabar teemed with slaves. At any moment, hundreds were confined aboard European Guineamen in the Cross River or at the houses of traders in preparation for sale to waiting ships. Many others were integrated into the fabric of Old Calabar society as domestic and agricultural laborers. Of these, some were little more than chattel, others carried on with great privilege, and a few were among the most powerful men on the river. But at moments such as the death of a great man, the subjugation at the base of every slave’s experience came to the fore—as it were slaves, almost exclusively, who perished during the funeral celebrations that followed.

At Edem Ekpo’s interment, the principal men of Old Calabar murdered nine slaves in the dead man’s honor. Weeks later, the residents of a settlement at the northern edge of the town “cutt one women slave head.” Six days later “3 head cutt of[f] again.” The next day a Taeon town man brought the head of a stranger in honor of Duke’s death. But the apogee of mourning came during a torrential rain in the early hours of November 6, four months after Ekpo’s demise, when a crowd of slaves was led into the great hall of the Ekpe Society—the fraternity of ruling men—to be decapitated by the gentlemen of the town: “5 clock morning we begain cutt slave head of[f] 50 head of[f] by the one Day. . . .”10

For enslaved Africans at Old Calabar, this kind of violence was ordinary, and the violence to slaves that punctuated the funeral celebrations of Edem Ekpo was of a kind that characterized all of the Atlantic slave trade.11 Whether in the Bight of Biafra at the emigrant center of the British empire or on Jamaica at the empire’s complimentary black immigrant core, captives forced to navigate such conditions emerged changed people.

![]()

ONE

THE SLAVE TRADE FROM THE BIAFRAN INTERIOR

Violence, Serial Displacement, and the Rudiments of Igbo Society

Who were they and where did they come from, the thousands of slaves who perished, passed through, or were integrated into the social fabric of Old Calabar, Bonny, and Elem Kalabari? Coming to terms with these two fundamental questions focuses attention on the matter of how enslaved migrants from the emigrant heart of the British empire were affected by their journeys. Contemporaries tended to speak of these unfortunates in ethnic national terms. Eighty percent of the slaves sold at Bonny, and a robust majority of those loaded at Elem Kalabari and Old Calabar, calculated slave trader John Adams, “are natives of one nation, called Heebo.” American planters engaged in the Africa trade and slaves knowledgeable about the trade in and around Biafra adapted a similar descriptive nomenclature. Gustavus Vassa, the eighteenth-century slave turned British abolitionist, described himself and the area in which he apparently lived as a boy as “Eboe,” and in a telling turn of phrase concerning the British slave trade, Jamaican planter Simon Taylor designated Guineamen that arrived at Kingston from Biafran ports as “Eboe Men.”1

Understandably, this has become the language of slave trade historians, too, and recent African diaspora scholarship has explored in detail the significance of various African nations in the Americas. Work on Igbo slaves in the New World describes what Igbo came to mean and represent in the Americas, and how Igbo slaves shaped and contributed to their new societies.2 But a foundational issue remains: Though Igbo slaves abounded on American plantations in the eighteenth century, there is very little evidence that there were people who understood themselves as such in the Biafran interior of the same time. Most students of Igbo migrants in the African diaspora acknowledge this point. Accounting for the apparent anomaly, however, and grappling with the issues it raises concerning the nature of Igbo society and the history of African nations in the diaspora remains largely undone. To date, African nations in the diaspora, Igbo among them, are generally understood as “the locus for the maintenance of those elements of African culture that continued on American soil.”3 This is undoubtedly true, but this is not all the nation was. Indeed, as far as the Igbo nation in the diaspora is concerned, this is more a description of one aspect of the nation’s potential as a social formation than it is an account of its origins. The origin of the Igbo nation in the diaspora was not simply a cultural imperative. At its base, it was also a social imperative born of migration—in particular the violent, alienating dislocation that characterized slave trading in the Biafran interior. In ways too important to ignore, the Igbo of the Americas were made so through their migrations.

The majority of slaves cast away from the Niger Delta, and a preponderance of those shipped from the Cross River estuary, originally hailed from a vast hinterland behind the Bight of Biafra, located in the southeast quadrant of present-day Nigeria. In the eighteenth century, society and culture across this region was as diverse as the landscape itself.4 Historically, the area was dotted with hundreds of independent polities, best referred to as village groups. In the main, these village groups were arrays of smaller settlements where ties of kith, kin, and proximity informed political and economic cooperation, as well as a certain corporate feeling and identification. Village groups themselves divided into smaller settlements, which were in turn sets of individual, patrifocal compounds physically connected one to another by series of paths. Spatially and politically, the internal organization of individual village groups varied throughout the region. Some were rather compact units led by congresses of leading men distinguished by their age and experience. Others were far-flung affairs governed collectively by the prominent men of certain titled societies. Yet others resembled small kingdoms, with political power concentrated into the hands of a single ruler.5

The inhabitants of the region spoke a group of related dialects. Yet language in the Biafran interior, as with forms of political power, was significantly localized. Linguistic patterns varied—sometimes slightly, sometimes quite significantly—from village group to village group. The dialect spoken at Onitsha in the late eighteenth century, for example, probably prevailed scarcely twelve miles to the south and a scant five miles east. Traveling west, it survived only in the talk of traders. Frontiers of dialect and language could be even more extreme farther east, particularly along the Cross River. Nevertheless, with mutual adjustments in grammar, tone, and locution, men and women from different locales could often make themselves understood to one another. But the feat was not transparent. It often could not be effected without conscious effort or recourse to some experience in such matters; neither could it be accomplished without revealing degrees of social and cultural differentiation between the speakers. And sometimes, for all intents and purposes, cross-dialect communication was simply impossible.6

An abiding localism centered on the village group characterized society and culture in the eighteenth-century Biafran interior: No manifest institutional authority exercised control over any significant part of the region; a plethora of locally focused aesthetic ideas flourished the area over; and a mosaic of dialects colored various corners of the whole expanse. The village group—its land, its politics, its rituals, and its dialect—was often the largest corporate unit.7

This is not to say that there did not exist general principles that informed life and labor the region over. Yam cultivation, for instance, predominated throughout the region, and the dialects of the Biafran interior were just that, dialects of a larger tongue. And some political and philosophical ideas possessed a wide currency. An imperialism of ideas centered on titles of personal achievement and rituals associated with the fertility of the land, for instance, radiated from the Nri village group in the Anambra River basin out toward many other settlements in the region. Neither was the localism of the Biafran interior akin to stagnation or isolationism. Village groups were connected by extensive ties of trade, marriage, conflict, and consultation, and every village group was itself something of a growing, living, social organism—colonizing new ground, acculturating new members, breaking off from previous concerns, and sometimes dying out altogether.8

Nonetheless, the expansion and transformation of various village group-based polities informed rather than mitigated against the essential localism of the area as a whole. Village groups, for instance, did not so much expand as segment, and hegemony was a more common outcome of conflict than was actual conquest.9 Political and cultural expansion in the Biafran interior invariably resulted in new or transformed localisms rather than real imperialisms. Similarly, the cultural and political principles preeminent across the region did not so much inform broad generalization as enforce the importance of particularism, for the cultural and political notions that were perhaps most widespread and deeply rooted throughout the Biafran interior were ones that undermine normal generalization: namely, individualism and personal achievement.10

Accordingly, it should come as little surprise that the peoples of the Biafra...