eBook - ePub

Slavery and American Economic Development

A Novel

Gavin Wright

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Slavery and American Economic Development

A Novel

Gavin Wright

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Through an analysis of slavery as an economic institution, Gavin Wright presents an innovative look at the economic divergence between North and South in the antebellum era. He draws a distinction between slavery as a form of work organization—the aspect that has dominated historical debates—and slavery as a set of property rights. Slave-based commerce remained central to the eighteenth-century rise of the Atlantic economy, not because slave plantations were superior as a method of organizing production, but because slaves could be put to work on sugar plantations that could not have attracted free labor on economically viable terms.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Slavery and American Economic Development an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Slavery and American Economic Development by Gavin Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Slavery, Geography, and Commerce

In recent decades, economic historians have rediscovered both the centrality of African slavery for the eighteenth-century expansion of commerce known as the Rise of the Atlantic Economy, and the importance of overseas markets for the industrial and technological breakthroughs known as the Industrial Revolution. The number of Africans transported to the Americas between 1700 and 1820 was five times larger than the number of free European migrants, and slave-based products dominated the long-distance markets of that era. To invoke another phrase from an older generation of economic historians, slavery was at the heart of the Commercial Revolution, which set the stage for the modern era of economic growth. The process of coming to terms with these historical relationships has barely begun and will no doubt occupy us for some time into the future.

This chapter assuredly does not undertake a full historical accounting, but it addresses a question often neglected in the literature. What was it about slavery that made it so vital to the emerging commercial economy? The weight of the evidence suggests that the rise of African slavery in the Americas was not primarily attributable to its advantages in production, but to the features identified in the introduction as property rights. Propositions about the “relative productivity of slave and free labor” are usually ambiguous for this simple reason: most of the time, slaves were working at tasks and in locations that could not attract free workers on commercially viable terms, so that we can never keep “other things equal” in making such comparisons. Labor relations and work performance varied widely, but this distinctive feature of slavery—the assignment of workers to tasks and geographic settings they would not voluntarily have chosen—was enduring and explains why slavery was crucial to the rise of the Atlantic economy.

WHAT HAS BECOME OF THE WILLIAMS THESIS?

Since its publication in 1944, Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery has stood as a benchmark or reference point around which discussions on the economics of the British slave trade and Caribbean slavery have revolved. In briefest summary, Williams maintained that the profitability of Britain’s slave colonies caused or at least helped to establish conditions favorable to the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century. As a corollary, Williams saw the movement to abolish the slave trade as driven by economic rather than humanitarian motives, reflecting the decline of the sugar economy and the emergence of new industrial economic interests. “Great mass movements,” Williams concluded, “and the anti-slavery mass movement was one of the greatest of these, show a curious affinity with the rise and development of new interests and the necessity of the destruction of the old.”1 How has this provocative thesis fared in the wake of subsequent scholarship?

For a full generation, the Williams thesis was dismissed by Anglo-American writers as an exaggerated caricature, a reflection primarily of underlying hostility toward both the British and capitalism. But research of recent decades has gone far to confirm the essential accuracy of that portion of the argument putting slavery at the center of the commercial revolution that laid much of the foundation for the industrial revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. African slavery was essential for Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch trade in sugar, spices, and precious metals. In light of the high mortality rates of indigenous populations and the great difficulties experienced in recruiting European labor voluntarily, it was only African slavery that made it possible to exploit the commercial potential of colonial conquests. Barbara Solow points out that early transatlantic commerce was dominated by sugar, extending a pattern of slave-based tropical export agriculture that predated Columbus, referred to by Philip Curtin as the “plantation complex.” British colonization efforts were essentially failures from a commercial standpoint until Britain’s entry into the slave-sugar network of the Caribbean in the seventeenth century.2

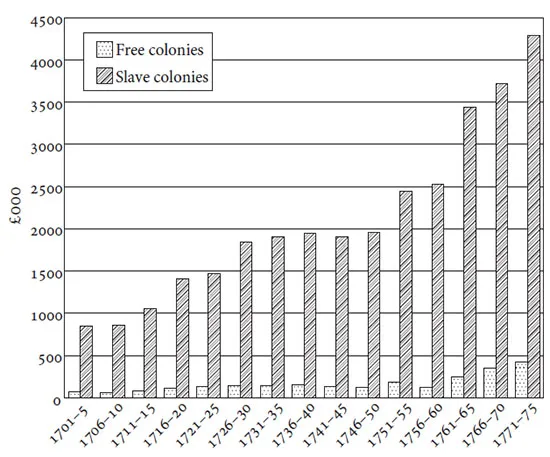

FIG. 1.1. British American exports to England (£000), 1701–75

Sources: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1176–77; Schumpeter, English Overseas Trade Statistics, 18.

Prior to the nineteenth century, the “wealthiest and most dynamic regions of the Americas” were worked and populated primarily by slave labor. Figure 1.1 divides the exports to England from British North America into those from “slave” and those from “free” colonies, defining those terms retroactively according to the political choices made regarding slavery after the American Revolution. It is obvious at a glance that slave-produced commodities were predominant and that their relative importance continued throughout the eighteenth century. If anything, figure 1.1 understates the matter, because it does not include the exports of Chesapeake tobacco to Scotland, which flourished from midcentury onward. At the time of the Revolution, total and per capita wealth levels of the slave colonies were far greater than those of their protofree counterparts.3

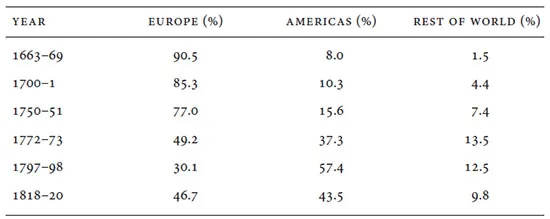

Long-distance trade was a leading sector for the British economy of the eighteenth century, growing more than twice as fast as national income. There is no economic magic in long distance per se: in the abstract, domestic demand may serve just as well as a stimulus for new industries. But in the mercantilist world of the eighteenth century, overseas markets lent themselves much more readily to rapid expansion through imperial linkage, and perhaps as much as 95 percent of the growth in the volume of British commodity exports went to imperial markets. In turn, the largest share of this growth was in trade with the Americas, as shown in table 1.1.4 These British exports were exchanged for American goods, more than 80 percent of which were produced by African slave labor, as estimated by Joseph E. Inikori.5 The result was, in the words of mercantilist Malachy Postlethwayt, writing in 1745, “a magnificent superstructure of American commerce and naval power on an African foundation.”6

Taken together, the evidence suggests that there are more than a few grains of truth in the Williams thesis, long considered moribund. It was not that “slave trade profits” flowed through some fiendish channels into the dark satanic mills. But the burgeoning Atlantic trade of the eighteenth century derived its value from the products of slave labor and would have been much diminished in the absence of slavery. As sugar became an item of common consumption in Britain, the sugar trade provided a powerful stimulus for a diverse range of occupations and ancillary activities, especially in London.7 The efficiency of ocean shipping improved markedly across the eighteenth century, not primarily through technological advances, but as a result of gains in economic organization and reductions in risk: a “revolution of scale” in the words of Jacob M. Price and Paul G. E. Clemens.8 Two round-trips per year became the norm as opposed to one. The importance of overseas trade for institutional development in shipping, finance, and marketing can scarcely be exaggerated. According to Price, the most striking and distinctive peculiarity of British commercial organization in this period was the extension of long credits by warehousemen and wholesalers to exporters, contracts that depended on the scale of trade for their viability.9

TABLE 1.1 Destination of English exports, 1663–1820

Source: O’Brien and Engerman, “Exports and the Growth of the British Economy,” 186.

Ultimately the Industrial Revolution was defined by the discontinuities in production technology that accelerated in the latter part of the eighteenth century. A full review of this venerable subject is well beyond the scope of these essays. But it is not inappropriate to observe that in recent decades both economists and historians have developed renewed appreciation for the role of expanding markets in encouraging innovations. In economics, the emerging body of thought known as “new growth theory” associates an expansion of market scale with an environment conducive to innovation.10 Among economic historians, detailed accounts portray an endogenous transition from midcentury Smithian innovations in products and marketing to the more famous Schumpeterian inventions of the 1780s and 1790s, featuring many of the same industries and entrepreneurs. Even before 1800, the cotton textiles industry had reached a scale large enough to support specialized machine makers, whose ongoing innovations and marketing efforts served to spread the technologies of the Industrial Revolution around the globe in the nineteenth century.11

Can we say, therefore, that African slavery was the cause of the industrial revolution? One may argue with some justification that it is anachronistic to assign pivotal causal significance to one element (African slavery) in a larger structure, when that element was itself an endogenous outgrowth of centuries of seafaring, conquering, and planting by aggressive, expansionist Europeans.12 We are in effect asking a hypothetical thought-question: whether the rise of the Atlantic trading economy could have occurred as it did if slavery had somehow been abolished centuries earlier. But why single out that necessary condition, as opposed to any number of others? Even if we do, if the objective is to explain the Anglo-American economic successes of the nineteenth century, its slave origins are clearly only a necessary and not a sufficient explanation. Whatever Britain had that Spain, Portugal, and Holland did not, access to slavery was not the differentiating factor. David Eltis has shown that Britain became the world’s leading shipping nation by 1650, well before its involvement with the slave trade, a superiority that he attributes to superior credit facilities, lower cost of services, and the impact of the Navigation Acts in excluding Dutch competition. In turn, the productivity advantage in shipping allowed the British to dominate the African slave trade by 1800, supplying not only its own colonies but those of Spain and other nations as well.13 As the international economist Ronald Findlay argues, “slavery was an integral part of a complex intercontinental system of trade in goods and factors within which the Industrial Revolution, as we know it, emerged. Within this system of interdependence, it would make as much or as little sense to draw a causal arrow from slavery to British industrialization as the other way around …”14

How this history might have looked without slavery is not a question that arises naturally from known forks in the path of history. Such a question acquires its bite only from the perspectives of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when slavery had come to be an unthinkable barbarity and the institutional forms of England had come to be identified with something called capitalism. Slavery was somehow a central and integral part of the process, yet its effects became enduring and historically significant only in conjunction with other fundamental developments in the economic and technological world. Stanley Engerman points out that England’s more dynamic development relative to France was not based on superior performance of the British sugar colonies compared to that of the French.15 Evidently the critical ingredients lay elsewhere, or perhaps in the British imperial package taken as a whole.

It may be beyond us to say precisely the extent to which African slavery was indispensable to the rise of the modern economic world. What we can do is pose a question that is often not asked in this burgeoning literature: What was it about slavery that made it so central to commerce in the premodern world?

THE GAINS FROM SLAVERY:

PRODUCTIVITY VERSUS PROPERTY RIGHTS

Central to the rise of African slavery in the Americas were the features identified in the introduction as property rights, specifically, the right of a slaveowner to employ the slave in a location and at an activity of the owner’s choosing, ignoring any preferences on the part of the slave. Robin Blackburn has proposed a counterfactual history in which slavery had been banned very early, suggesting that the need to recruit free labor would have set development on a more positive social, political, and economic path. But other scholars reject this scenario as utterly anachronistic. David Eltis, who has devoted years to analyzing the evidence on transatlantic migration, concludes that more than 60 percent of all transatlantic migrants were African slaves prior to 1700, the share rising to 75 percent in the eighteenth century. It was not until the 1840s that voluntary European migration first exceeded the volume of the slave trade, and those Europeans who did come “generally stayed well away from the tropical zones.” Similarly, Seymour Drescher writes that, for the kinds of enterprises in which slave labor predominated, “other forms of labor would have been available only at much higher prices.”16

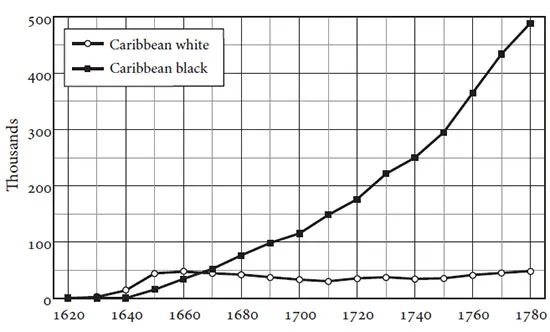

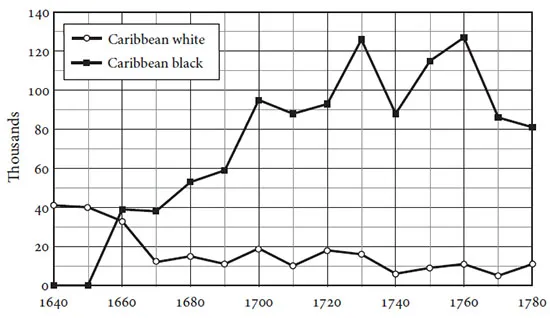

It is true that the early English plantations on Barbados and in the Chesapeake drew upon white indentured labor, an institutional form whose coercive features gave employers a degree of control that would hardly constitute free labor by modern standards. But indentured servitude was ultimately a contractual arrangement, voluntary in the sense that the servant could refuse the offer if the prospective employment were sufficiently grim. David Galenson’s econometric estimates show that servants bound for the West Indies received shorter terms (by as much as eight to nine months) than those going to the mainland, indicating that the mainland was strongly preferred. Those who did go to Barbados hastened to leave as soon as their terms were completed. Only when indentured servitude was replaced by slavery did British Caribbean population and exports grow significantly; from that point forward, the white population ceased to expand and in fact declined (fig. 1.2). Small wonder: death rates exceeded birthrates by a considerable margin, so that the population grew only through a continuing influx of African slaves (fig. 1.3). Mortality was generally better on the mainland. But in South Carolina, efforts to attract or retain Irish labor were generally unsuccessful because of negative publicity and persistent rumors that terms of servitude would be extended involuntarily. Competition with other colonies forced a reduction in the length of contracts, while statutes imposed caps on terms and required that servants receive clothing and provisions when their terms were completed. The major advantages attributed to African slave labor were that terms of service were unlimited and that labor supply was unresponsive to adverse rumors.17

FIG. 1.2. Population of British Caribbean, 1620–1780

Source: McCusker and Menard, Economy of British America, 153–54.

FIG. 1.3. Net migration to British West Indies, 1630–1780

Source: Galenson, “Settlement and Growth of the Colonies,” 178, 180.

In addition to locational preferences, work in the sugarcane fields—the destination of perhaps two-thirds of African slaves—was associated with death rates that were substantially higher than those resulting from work with other crops. According to Philip D. Morgan, sugar entailed “literally a killing work regime” for reasons of both the hostile disease environment and episodic stress. It did not take long for word to spread: white labor in Barbados “soon learned of [sugar’s] rigors and avoided it at all costs.”18 In light of these conditions, it is difficult to see how the Atlantic sugar trade could have flourished as it did in the absence of slavery or something similar to slavery. As mercantilist Sir James Steuart asked in 1767: “Could the sugar islands be cultivated to any advantage by hired labor?”19

Perhaps these points are obvious, almost part of the definition of slavery as “involuntary servitude.” Yet for some reason historians often seem to feel obliged to explain the rise, spread, and persistence of slavery in terms of advantages in productivity, commonly associated with the intensity of the work pace. Thus Barbara Solow writes that slave labor was “elastically supplied and especially productive in crops of widespread importance,” while Eltis asserts (citing nineteenth-century evidence) that “the productivity advantage lay with the coerced rather than the free labor regions of the Atlantic.” At times Eltis seems virtually to equate work intensity with productivity, as when he describes American slavery as involving “exploitation more intense than had ever existed in the world,” and then proceeds to elaborate in the next sentence: “It is inconceivable that any societies in history—at least before 1800—could have matched the output per slave of sevente...