![]()

Chapter One

The Great Commission

Watershed Conquest or Watershed Discipleship?

Katerina Friesen

During a college internship program I lived with an Ikalahan host family in Imugan, a town in the Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Luzon, the Philippines. I often accompanied my host mother, Auntie Noemi, to tend her family’s subsistence farm, where she grew many varieties of sweet potatoes, peanuts, beans, squash, garlic, and ginger. My host father worked as a pastor and community forester, maintaining the dipterocarp, pine, and cloud forests and protecting the people’s traditional “Ancestral Domain” against illegal loggers and other intrusions.

Auntie Noemi.

Rampant resource extraction in the form of mining and logging, both legal and illegal, has profoundly impacted Indigenous communities in the Philippines. Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) is a promising response to the failure of state governance to protect the forests. CBFM puts forest management in the hands of local communities like the upland peoples with whom I stayed, and draws from their traditional knowledge to regulate sustainable forest use (see Guiang, Borlagdan, and Pulhi 2001). Legal recognition of the Ikalahan-Kalanguya Ancestral Domain, also called the Kalahan Forest Reserve, was the result of a secure land tenure agreement between the government of the Philippines and the Ikalahan people in the 1970s, the very first of its kind (Roxas 2006). A watershed centrally defines the 36,000 acre Domain; draining into the Magat River, it serves as a sanctuary to more than 150 endangered species of plants and animals. The people have decided collectively to protect their watershed; thus, those who live near sources of water cannot expand their farms, raise livestock intensively, or use chemical pesticides on the land. As a local community, they have limited their own potential growth for the sake of the well-being of the whole watershed, including the lowland peoples who live downstream.

Auntie Noemi told me that when her parent’s generation converted to Christianity in the 1960s, they decided to expand their faith instead of their gardens. She contrasted their decision with communities outside of the Ancestral Domain who have denuded their once-forested slopes to make room for mono-crop agriculture that grow produce for distant markets. This kind of farming has created drastic erosion, and local people attribute an increase in cancer in those areas to the heavy use of synthetic chemical inputs. For the Ikalahan, Christian faith and care for their watershed go hand-in-hand.

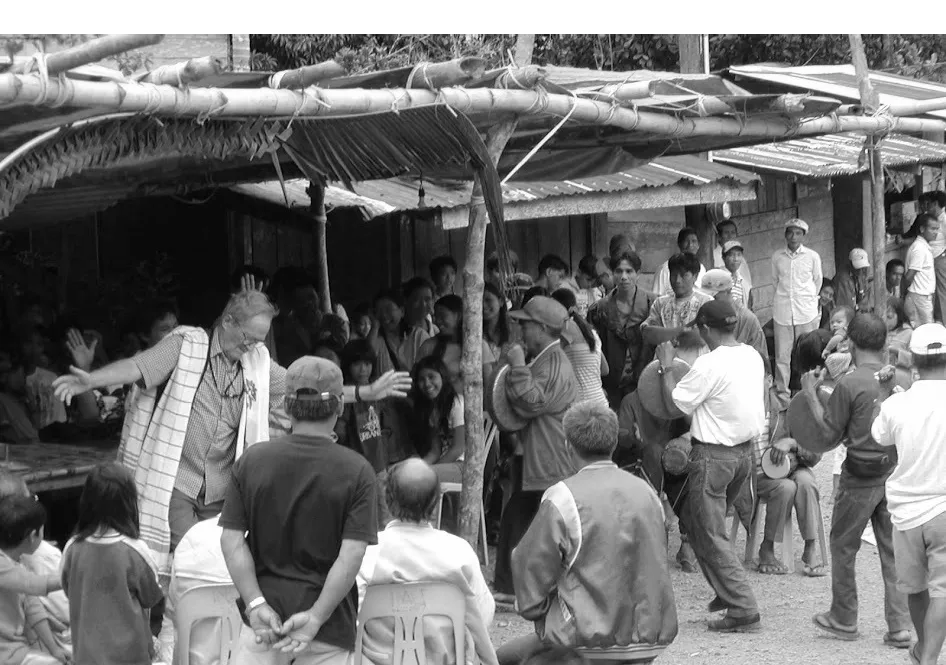

Pastor Delbert Rice dancing the traditional tayaw.

The holistic mission strategies of Pastor Delbert Rice significantly strengthened the Ikalahan’s commitments. Rice (left in the photo) was a missionary with the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), and lived in Imugan from 1965 until his death in 2014. In contrast with other Protestant missionaries who had made evangelistic visits to the area starting in the 1930s, Rice did not preach against traditional practices like the kanyaw and the baki ritual feasts. Instead, he let the people decide which traditions to continue, which to reject, and which to adapt in light of their Christian conversion (Lee 2014). In his later years, Rice came to see learning, teaching, and promoting upland forest ecology as integral to his work as a missionary. The Christian gospel resonated with certain Ikalahan concepts, such as li-teng, which forms the basis for the people’s care for their watershed. Li-teng is a deeply ecological word signifying abundant life for all, which Rice analogized to the Hebrew shalom (Native American theologian Randy Woodley has made similar analogies to the “Harmony Way” common among many Indigenous peoples, 2012). With their Christian faith strengthening certain traditional cultural and ecological practices, the Ikalahan have become a model throughout Southeast Asia for their CBFM practices, Indigenous educational programs, and ongoing expressions of restorative justice through the tongtongan, or council of elders.

Historically, Spain, the U.S. and Japan have all colonized or occupied the Philippines. The Ikalahan people have a long record of resistance. They have organized against: illegal logging; a “Marcos City” resort planned in the 1970s under the dictatorship; cell phone satellite towers; and most recently, Australian mining companies (Dumlao 2014). Love for the naduntog nakayang, “the high mountain forest where the clouds settle in mist around the trees,” has compelled their struggle. Their home is worth defending with their lives. During my six months living with the Ikalahan, however, I became increasingly aware of a significant gap in my own life. I began to ask myself: Was there a place for which I would put my life on the line? I did not know.

I grew up in a missionary family that then remained highly mobile. By age twenty-one I had moved ten times. I became accustomed to an ambivalent intermingling of emotions—the pain of leaving friends and place, but also the tingle of excitement associated with traveling somewhere new. I envisioned myself working overseas, living the exhilarating life of a global nomad. No place held any claim over me, and I had no desire to limit my life to one place—until I lived within the Ikalahan Ancestral Domain. There the people’s love for their home opened my eyes, and exposed the placeless dreams that were scripting my life goals.

Before I left the Philippines, my host family held a prayer service attended by local elders and friends. The pastor stood to give me a commission, and prayed that I would return home to the U.S. to apply what I had learned with them. This simple and profound commissioning changed my life, initiating a journey of repentance that turned me toward home.

Commissioning ceremony in the Philippines.

I. Commissioned Toward Home

Returning from the Philippines I felt disturbed by the fact that my own sense of home seemed as distant as a foreign land. This condition, I believe, is not unique, but reflects a widespread social-spiritual malady facing North American Christians today which, among other problems, poses a threat to the church’s cross-cultural witness and mission. Without a sense of home, missionaries run the risk of sharing a gospel disinterested in place, abstracted from the geography of the watershed. As Jonathan McRay writes in Chapter Three of this volume, modern white Christians often forget that “land is not a commodity but a community of soil, water, air, plants, animals, and humans.” Land is home and life.

Mission has been understood historically in terms of leaving home for the sake of spreading the gospel elsewhere. Perhaps no biblical verb has been as significant to the history of mission as the first one in Matthew’s Great Commission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing . . . and teaching them . . . ” (Matt 28:19–20a). This exhortation does not inherently imply rootlessness or estrangement from the land—after all, it was delivered by and to Palestinian Jews who were deeply grounded in place. Yet the partnership of missionaries and imperialism beginning in the fifteenth century with the “Age of Discovery” meant that the Great Commission began to be understood in terms of conquest, through a theological anthropology that separated people’s souls from their bodies and their lives from the land.

In their introduction to Teaching All Nations: Interrogating the Great Commission, Mitzi Smith and Jayachitra Lalitha summarize this approach: