![]()

Chapter One

Hercules Conquers the Box Office

Mythological Epics

Though they had been making impressive ancient spectacles since the silent era, the Italians’ craze for mythological epics began in earnest in 1958. Making these epics was partly a way of utilising sets and costumes from Hollywood productions – including Quo Vadis (1951) and Helen of Troy (1955) – which had been filmed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. Christened ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’, Cinecittà was a vast studio complex opened by Mussolini in 1937. Italian productions capitalised on the vogue for ancient spectacles (‘Big Screens Mean Big Themes’ went the publicity for Helen) by taking an already popular genre – the sword and sandal epic – and making it their own. Such films were christened ‘peplum’ (plural ‘pepla’) by French critics after the Greek word ‘peplos’, the name of the short skirts worn by the heroes.

The most popular stars were Steve Reeves, Reg Park and Gordon Scott: muscly outdoor types whose sheer bulk and screen presence compensated for their thespian shortcomings. Several of these musclemen – including Mickey Hargitay, Reg Lewis, Gordon Mitchell and Dan Vadis – had been bodybuilders in Mae West’s risqué touring stage review in the US. There was also a phalanx of pseudonymous Italian musclemen – for example, stuntman Sergio Ciani became ‘Alan Steel’ and ex-gondolier Adriano Bellini was billed as ‘Kirk Morris’. They played heroes named Hercules, Goliath, Ursus, Samson and Maciste. Ursus and Maciste were unfamiliar to English-speaking audiences, so many of their adventures were dubbed into Hercules or Goliath vehicles. Embassy Pictures released several as the ‘Sons of Hercules’ series, with a rip-roaring ‘Sons of Hercules’ title song: ‘On land or on the sea, as long as there is need, they’ll be Sons of Hercules!’ If the truly ‘epic’ biblical epics of Hollywood director Cecil B. De Mille were famous for giving cinemagoers more than their money’s worth, then peplum audiences sometimes felt a little short-changed.

The central theme of pepla is man’s freedom. Often an oppressive overlord is misruling with vigour, enslaving the populace. With help from the hero the slaves cast off the shackles of oppression, an act representing a symbolic image of freedom that was a genre signature. There is often a wily, morally bankrupt queen (who desires the hero) and a virtuous heroine (for him to save from danger). Recurrent elements include torture, tests of strength, a cataclysm (usually an earthquake) and at least one cabaret spot by a group of dancing girls as court entertainment, to eat up the running time. Sometimes the hero is lifted completely out of his mythological context – Hercules against the Sons of the Sun shipwrecks its hero in South America, Maciste in Hell is set in Scotland – but to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, it’s possible to believe anything provided it is incredible.

Hercules the Mighty

The trigger film for these ‘bicepics’ was Pietro Francisci’s Hercules (1958), ‘freely adapted’ by Francisci from The Argonauts written by Appollonius of Rhodes in the third century BC. Francisci cast American Mr Universe winner Steve Reeves as Hercules opposite Yugoslavian starlet Sylva Koscina as Iole, King Pelias’ daughter. Francisci had already had success with Attila the Hun (1954), which paired Anthony Quinn and Sophia Loren. Immortal Hercules is summoned to the city of Iolcus in Thessaly by Pelias (Ivo Garrani) to teach his braggart heir Iphitus (Mimmo Palmera) the art of war. Iphitus is savaged to death by a lion while in Hercules’ care and the hero renounces his immortality. Jason (Fabrizio Mioni), the rightful heir to Pelias’s throne, is sent to retrieve the Golden Fleece from Colchis. On board the Argo, built by Argos (Aldo Fiorelli), Jason gathers the Argonauts – the musician Orpheus (Gino Mattera), the Dioscuri (twin heroes) Castor and Pollux (Fulvio Carrara and Willi Columbini), Ulysses (Gabriele Antonini) the son of Laertes (Andrea Fantasia), Tifi the pilot (Aldo Pini) and Hercules. Pelias’s henchman Eurystheus (Arturo Dominici) tags along to sabotage the trip. The questers are distracted on Lemnos, Island of the Women, where Jason falls for Antea, alluring Queen of the Amazons (Gianna Maria Canale). Later the Argonauts are ambushed by ape men in Colchis and Jason fights a dragon guarding the fleece, before returning to Iolcus to claim his throne.

Hercules was shot in Eastmancolor and French widescreen process Dyaliscope and is accompanied by a score by Enzo Masetti. Musical highlights include the lush title theme; the jaunty ‘Athletes’ theme; a lusty sailors’ choir led by Orpheus; the theramin-led Sirens’ theme; and love themes for Hercules and Iole, and Jason and Antea. Lidia Alfonsi played oracle ‘the Sybil’ and future Bond girl Luciana Paluzzi was Iole’s handmaiden. Exterior footage was lensed at the Nature Reserve and beach at Tor Caldara, Anzio Cape, with palace interiors at Titanus Studios, Rome. Hercules’ farewell to Iole was filmed at the arching fountains in Rome’s EUR district; the athletes’ games, where Hercules humiliates Iphitus, were also staged in EUR. Mario Bava’s lighting and special effects are impressive and there are some memorable settings: the volcanic Island of Lemnos (a tropical paradise of palm trees, parrots and cascading flowers) and the tiered waterfall at Monte Gelato in the Treja Valley, Lazio. Antea’s glittering grotto is festooned with stalactites, flowers (courtesy of Sgaravatti of Rome) and what appear to be strips of shimmering clingfilm. The Italian title (Le fatiche di Ercole) translates as ‘The Labours of Hercules’, though only two of the Twelve Labours feature: the strangling of the Nemean lion and the capture of the Cretan Bull (represented by a North American bison).

Hercules was a colossal success, especially in the US in 1959 where it grossed $20 million when independent Boston producer Joseph E. Levine bought the US rights for $120,000 and spent $1.2 million on advertising, including the precedent-setting use of TV ads in what William Goldman called ‘the most aggressive campaign any film ever had’. Two different English language dubs of the film exist: the UK print opens with the titles over a Greek frieze, while the US version substitutes an animated starfield and a superior dubbing track. Distributed by Warner Bros, Hercules was one of their biggest hits of the year. Levine formed Embassy Pictures (later Avco-Embassy) as a result of this success and was later the producer of the Oscar-winning The Graduate (1967) and The Lion in Winter (1968).

Francisci’s sequel, Hercules Unchained (1959), was based on Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles (a dramatisation of the last hours of King Oedipus), The Seven against Thebes by Aeschylus (recounting the Theban Wars) and The Legends of Hercules and Omphale, again ‘freely adapted’ by Francisci. Hercules and his wife Iole (Reeves and Koscina), with Ulysses (Gabriele Antonini), land in Attica, Hercules’ home, to find King Oedipus (Cesare Fantoni) at odds with his sons, Eteocles (Sergio Fantoni) and Polyneices (Mimmo Palmera). Oedipus has decreed that each will rule Thebes for a year, but Eteocles refuses to cede power. Polyneices has laid siege to the city with his mercenary Argives. Francisci crowbarred Hercules into the story, casting him as a peace envoy. Hercules and Ulysses take a truce from Eteocles to Polyneices, but they are kidnapped en route by Lydian soldiers, who brainwash Hercules with ‘the waters of forgetfulness’. He becomes the love slave of Omphale (Sylvia Lopez), the Queen of Lydia. As Omphale tires of her lovers they are transformed into human statues by her Egyptian henchmen, in a steamy vitrification process. One critic noted, ‘Such a fate would have made little difference to Reeves’ performance’. Eventually a rescue party led by King Laertes frees Hercules, who rushes to Thebes where Iole is about to become tiger food in Eteocles’ arena.

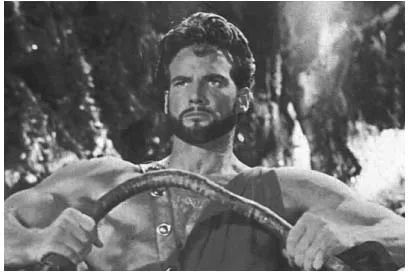

Steve Reeves flexes muscle in Pietro Francisci’s Hercules Unchained (1959), the first sequel to the phenomenally successful Hercules (1958).

Hercules Unchained is superior to its predecessor, with tighter plotting, punchier action and superior acting. Carlo D’Angelo appeared as Theban high priest Creon, Daniele Vargas played an Argive general, Gianni Loti was Sandone (Captain of Omphale’s guard) and future peplum stars Alan Steel and Giuliano Gemma appeared as officers. Ballerina Colleen Bennet was the Lydian court dance soloist and Patrizia Della Rovere played Penelope, Ulysses’ girl. Iole, plucking Orpheus’s lyre (called a ‘lute’ in the slapdash dubbing) serenades Hercules by miming to June Valli’s ‘Evening Star’ (lyrics by Mitchell Parish), the melody of which was used as the root of the film’s title music. En route to Thebes Hercules fights Antaeus, the son of the earth goddess (played by world champion boxer and wrestler Primo Carnera, ‘The Ambling Alp’). The film’s impressive finale features a pitched battle as the Argives wheel their siege towers to the gates of Thebes. Hercules leads the Theban counter-attack across the plain in a four-horse quadriga chariot, lassoing and toppling the Argive towers.

Mario Bava was again in charge of lighting and effects and the Dyaliscope cinematography in crisp Eastmancolor is a major asset. The sunny Italian exteriors – beaches, cliffs, valleys, cities and woodland – are amongst the finest in pepla. Exteriors were filmed in Lazio (including the coast at Tor Caldara and the Treja Valley), with interiors at Titanus Appia Studios. It is in the exotic landscape of Lydia where the production really scores. When Hercules drinks from a bewitched woodland spring, there’s a gnarly tree root shaped like a grotesque troll, with water pouring from its eye and the moss glistening magically. The Monte Gelato waterfall on the River Treja is bedecked with flowers for Hercules and Omphale’s tranquil idyll. During a scene between Hercules and Omphale in her grotto beneath a waterfall, the flowery backdrop changes colour as the seductive mood changes. Omphale, as played by French actress Sylvia Lopez, is a red-haired seductress. She sashays across the screen in a variety of diaphanous dresses and Ester Williams sequinned bathing suits, gossamer trailing in her wake, while Bava lushly bathes the sets in her radiated sensuality. Men, even the sons of gods such as Hercules, are hypnotised by her. Lopez’s portrayal of the doomed queen is movingly effective, particularly in light of her death from leukaemia at the age of 28 in November 1959. Levine again bought the rights, distributing the film through Warner Bros in the US and the UK in 1960. It made a fortune, through an intense TV advertising campaign which magnetised huge audiences into theatres.

Francisci returned to the Hercules saga with Hercules, Samson and Ulysses (1963). In Ithaca, Hercules (Kirk Morris), Ulysses and crew embark on an expedition to kill the Great Sea Monster. They are shipwrecked in Judea where they become embroiled in the rebellion against the evil ruler, the Seran (Aldo Giuffre), who is battling his enemy Samson (Iloosh Khoshabe, billed as the more easily pronounceable ‘Richard Lloyd’). In one of the most violent scenes in pepla, the Seran orders the razing of a village which has been sheltering Samson, crucifying many of the locals to the walls of their houses. Such horror is dissipated by the Seran’s soldiers’ World War II-era German helmets. The finale, shot at the beach and headland at Tor Caldara (decked with fake palm trees), had Hercules and Samson joining forces to jack up the Temple of Dagon, which collapses and buries the Seran’s army. When Delilah (a deliciously duplicitous Liana Orfei) attempts to entice Hercules to bathe with her in the Monte Gelato waterfall, he politely refuses (‘Not today Delilah’) and Hercules and Samson evidently prefer each others oiled company. Samson is so lubricated he appears to have been lacquered. For their big fight, the pair hurl outsized cardboard boulders, columns and masonry at each other.

Mighty Feats: In the Footsteps of Hercules

Between the release of Francisci’s first and last ‘Hercules’ movies, Italian pepla veered off in many directions. Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia’s The Loves of Hercules (1960 – Hercules Versus the Hydra) is told without pretension, attention to myth or logic. Hungarian bodybuilder and ex-Mr Universe Mickey Hargitay and his wife, busty Hollywood bombshell Jayne Mansfield, were cast as Hercules and Queen Deianara of Acalia. Hercules’ wife Megara and Deianara’s father Eurystheus are murdered by Lico (Massimo Serato) and his henchman Philoctetes (Andrea Aureli) who plan to usurp the throne of Acalia, while Hercules is falsely accused of killing Deianara’s lover, Achillos (Gil Vidal). Hercules slays the three-headed Hydra and falls under the spell of Amazon queen Hippolyta (Mansfield again), who transforms herself into the living image of Deianara. Escaping her domain, Hercules races back to the fortress of Acalia to lead the people in revolt against Lico.

Mansfield made the film in Italy when Hollywood studios refused to cast her opposite Hargitay. She had to diet during its making to conceal the fact that she was pregnant with her second child, but still looked fabulous in voluminous, colourful costumes, her blonde hair hidden beneath a black or purple hairpiece (for Deianara) and a burnished red wig (for Hippolyta). Giulio Donnini and Andrea Scotti were Lico’s devious high priest and Hercules’ faithful shield-bearer Temanthus respectively. Accompanied by a majestic score by Carlo Innocenzi and shot in the Italian countryside (the impressive gates of Acalia were built beside the Monte Gelato falls) and amid vast Acalian city sets at Cinecittà, Loves has several memorable action scenes. Hercules saves Deianara from a wild bull (which had to be tranquillised for the scene when Hargitay wrestles it) and also from Halcyone, a snaggletoothed ape. Hercules beheads the fire-breathing Lernean hydra (a puppet dragon) in a hokey scene which can be glimpsed in the 1968 mondo documentary The Wild, Wild World of Jayne Mansfield (released after the actress’s death by decapitation in a car accident in 1967). Loves’s surreal surprise is Hippolyta’s ‘Forest of Death’, where men she has loved live on as wailing tree creatures. Eventually one of the damned exacts revenge and strangles the evil queen with its branches. This murky Valley of Tree Men, which contributes some of the movie’s least wooden acting, was constructed at Tor Caldara.

Like Francisci’s Hercules, Riccardo Freda’s The Giants of Thessaly (1961) was inspired by the Golden Fleece saga. Set in 1250 BC, King Jason of Thessaly (Roland Carey) embarks on a quest to find the fleece – if he fails, the gods will destroy Iolcus with a volcanic eruption. Ziva Rodann played Jason’s wife Queen Creusa, Massimo Girotti was Orpheus and Luciano Marin was Eurystheus. Alberto Farnese was pointy-bearded despot Adrastes, who fancies Creusa (‘Her loveliness is ablaze in me like an open furnace’) and Raf Baldassarre plays Adrastes’ henchman Antius. The Argonauts land on an island of witches, ruled by Queen Gaia (Nadine Saunders), an enchantress who turns Jason’s crew into talking sheep. Gaia and Jason traverse a bubbling pool in a grotto on a floating throne, which resembles a peplum pedalo. The Argonauts save a city from a giant one-eyed gorilla (special effects were by Carlo Rambaldi) and Jason scales a colossal statue to retrieve the fleece. Shot on interiors at Cinecittà and the Instituto Nazionale Luce, with exteriors on the steps of Palazzo Della Civilta, EUR, Rome (the storming of Iolcus’s palace), Giants builds to a splendid conclusion. As Adrastes is about to marry Creusa, the Argonauts burst forth from statues in great plumes of fire.

Columbia Pictures’ version of the Golden Fleece saga, Jason and the Argonauts (1963), was lensed in picturesque locations in Campania, Italy, and at SAFA Studios in Rome. It featured Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion special effects in Dynamation 90 and Eastmancolor, with Nigel Green’s Hercules opposite Todd Armstrong’s Jason.

Goliath was second only to Hercules in popularity in the US and Vittorio Cottafavi’s Goliath and the Dragon (1960) was one of the most successful examples. The Italian version (‘The Vengeance of Hercules’) was a sequel to Francisci’s Hercules films. Emilius the Mighty, the ‘Goliath of Thebes’ (Mark Forrest), descends into the Cave of Horrors to retrieve the Blood Diamond for the Goddess of Vengeance, battles Cerberus the three-headed fire-breathing hell-hound (a puppet) and then wrestles a giant bat (a man in a giant bat suit). Eurystheus the Tyrant (Broderick Crawford), the scar-faced King of Ocalia, wants to take over Thebes. He murders Goliath’s parents and imprisons Goliath’s brother, Ilus (Sandro Moretti). Eventually, the Sybil (Carla Calo) foretells that Ilus will be King of Ocalia, but it will cost Goliath the life of his wife, Dejanira (Leonora Ruffo). Crawford is a fine villain, who dies in his own snake pit wresting a large rubber python. Gaby Andre appeared as evil Ismene, in league with Eurystheus’s advisor Tindar (Giancarlo Sbraglai). Wandisa Guida played slave Ancinoe, dispatched by Eurystheus to poison Goliath, and Federica Ranchi was Thea, Eurystheus’s daughter. Salvatore Furnari, as Goliath’s midget companion, was a peplum regular, working often with Cottafavi. Goliath wrestles a bear, prevents Ilus from being crushed by an elephant’s foot and tears down his own house when he realises he can’t enjoy a mortal’s life: ‘Collapse like my shattered dreams!’ he rages. Goliath enters the city’s underground caverns, smashing the stalactite support pillars, causing Ocalia to crumble. Dejanira is kidnapped by Polymorphus the Centaur (Claudio Undari), a less-than-convincing half man–half deer, though the spectacular setting for his arrival is the cascading Cascate Delle Marmore (Marmore Falls) in Umbria. Polymorphus escapes with Dejanira through billowing clouds of purple smoke. Goliath takes on the dragon, with stop-motion footage of the beast (animated by Jim Danforth) intercut with close-ups of Forest battling a puppet in the rock-hewn underground caverns at Grotte Di Salone, Lazio. The US release replaces Alexandre Derevitsky’s original score with new Les Baxter compositions.

In Cottafavi’s Hercules Conquers Atlantis (1961) the portents foretell that Greece is to be destroyed by an unknown menace from across the sea. King Androcles of Thebes (Ettore Manni) leads an expedition, taking Hercules (British bodybuilding champion Reg Park) with him. They are shipwrecked on Atlantis, which is ruled by Queen Antinea (Fay Spain), who has created a race of invincible warriors. Antinea gains her power from the blood of the god Uranus, now cast as a rock hidden deep in the Mountain of the Dead – Hercules destroys the rock with a sunbeam, causing the destruction of Atlantis, and saves the known world.

With lushly saturated cinematography by Carlo Carlini, in Technicolor and 70mm widescreen ‘Super Technirama’, Hercules Conquers Atlantis is one of the most visually sumptuous epics of the 1960s that holds its own with its Hollywood contempor...