![]()

Peiper Advances, Saint-Vith Resists

On the evening of December 16, Eisenhower began implementing his response: reinforcing Middleton’s VIII Corps by taking the 7th Armored Division from the Ninth Army and the 10th Armored Division from the Third Army. Moreover, the First and Third Armies began mobilizing in the threatened sector. On the ground, General Middleton, in charge of the VIII Corps, took the measures he deemed necessary with the limited means at his disposal: blocking access to the four most important road junctions of the sector, Saint-Vith, Houffalize, Bastogne, and Luxemburg City. Middleton had only one thing in mind: to stop or delay the Germans sufficiently to give time for the 12th Army Group to launch a massive counterattack.

On the German side, Kampfgruppe Peiper’s breakthrough was not the deepest, but it was the first one. It was widely photographed, probably because it involved a Waffen-SS unit at a time when Hitler had lost faith in the Heer.

Defending Wiltz, December 20, 1944: B Company, 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion, in their foxholes awaiting the enemy. (U.S. National Archives)

In Profile:

Sturmgeschütz III and IV

A StuG IV from 200th Tank Destroyer Battalion,of the Führer Begleit Brigade, December 1944. This unit fought at Bastogne with the 5th Panzer Army.

A StuG III G of 2nd Company, 115th Panzer Battalion which received 30 units of this type just before the start of the Ardennes offensive.

A StuG 40 G, from an unidentified unit, during the Battle of the Bulge.This kind of machine was widespread, and could even be found in the volksgrenadier divisions.

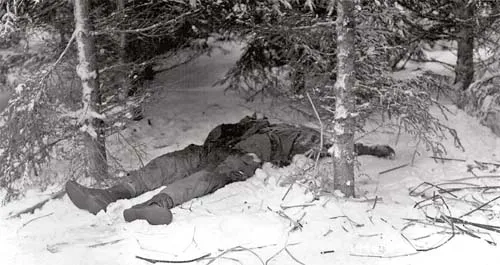

A soldier from the 101st Airborne Division, killed in the defense of Bastogne. (U.S. National Archives)

Battle Group Peiper Advances

On the evening of December 16, Peiper was trapped around Lanzerath, hindered both by the traffic congestion and by Colonel von Hoffmann’s 9th Parachute Regiment, reluctant to advance without some artillery support. Peiper did not know it yet, but the opposition at Saint-Vith would isolate him from the 5th Panzer Army which was advancing much farther west than him.

This vehicle, built on the chassis of a Panzer III, was destroyed in the northern outskirts of the town of Luxemburg. Because of the snow, superstructures are hard to identify, but the six wheels leave no doubt as to the frame. (U.S. National Archives)

Two GIs killed in Honsfeld. The one in the foreground has been relieved of his boots. (U.S. National Archives)

A Sherman from Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division in a static role at Bastogne. The aim was not to advance and attack the Germans’ left flank, but to help the 101st Airborne to hold their position. (U.S. National Archives)

From midnight, Kampfgruppe Peiper left the village, driving through small forest roads on a dark night. The paratroopers ahead of Peiper captured the next village, Buchholtz, without resistance. Around 0600, before day had even broken, the panzers were approaching Honsfeld, where they blended in with the American traffic. The surprise of the village’s defenders, belonging to the U.S. 14th Cavalry Group and to the 99th Infantry Division, was absolute. They did not offer any resistance, trying to escape rather than giving themselves up. Peiper reported capturing 50 reconnaissance vehicles (M8s and half-tracks, but also a lot of Jeeps), 80 trucks and 15 anti-tank guns.

However, the paratroopers’ advance effectively bogged down. As for Peiper, he resumed his attack westward. The 99th Division having requested air support, some P-47s intervened at daybreak against the Kampfgruppe. At least one Wirbelwind, a Flakpanzer IV, was destroyed as were some unarmored vehicles, but the Flak replied and took down at least two fighter-bombers.

This air raid surprised many American units, including the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, whose men realized suddenly that the Germans had penetrated deep inside American lines. Peiper was not alone either, since Kampfgruppe Hansen, which also belonged to the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, was advancing on a parallel road. The American troops, be they 291st Engineers or 14th Cavalry Group, were too few to try to oppose the Waffen-SS effectively. They neatly withdrew. Toward 1700, the 14th Cavalry Group was in position near Poteau while its CO was trying to make his way toward Saint-Vith. He would eventually get there, having faced many dangers, including losing his Jeep to German fire, but would end up losing his command. His unit was destroyed at Poteau, as testified by the many photographs taken at the time, which are among the most famous images of the Battle of the Bulge.

The corpse of an American soldier is carried off on a stretcher at Malmédy. (U.S. National Archives)

In Profile:

War Crimes Part I

The massacre by the Waffen-SS of American GIs at the Baugnez crossroads has forever come to be known as the Malmedy Massacre, when Joachim Peiper’s stormtroopers of the 1st SS Panzer Division machine-gunned 84 American prisoners of war in cold blood on December 17, 1944. It started when Peiper’s Kampfgruppe came across a convoy of around 30 U.S. trucks, principally elements of B Battery, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, negotiating the crossroads. Immobilizing the front and last vehicles, the rest of the convoy, along with over a hundred GIs, were taken prisoner.

Most of the Americans assumed it was a routine stop and hopped off the vehicles, unarmed. One survivor of the massacre, Private Eugene Garrett, later recalled how he suddenly saw Waffen-SS troopers swarming over the trucks, rounding up GIs and stealing their valuables. A U.S. officer protested: a Waffen-SS officer put a pistol to his forehead and shot him dead. Garrett happened to mutter “Son of a bitch” and was promptly beaten about the body by a German rifle butt, the captor saying in perfect English, “This will teach you to cross the Siegfried Line!”

The main SS column moved off and the Americans were then herded into a neighboring field where they were gathered together in a large group. Shortly thereafter, a German half-track drove into the field. A Waffen-SS officer alighted from the vehicle, and, according to Garrett, who happened to be right at the back of the group, approached an American medic wearing a red cross on his helmet and shot him dead at point-blank range. This was the signal for the German machine guns to open fire. At a later postmortem, it seemed that many of the victims were then administered a coup de grâce with a bullet to the back of the neck, or clubbed to death with rifle butts. Several survivors managed to run to a nearby shed but were burned alive by the pursuing Germans who set fire to the building.

Peiper Runs Out of Gas

During the course of the battle, the Germans were hindered by their lack of gasoline, which was not due to a shortage per se, as Keitel had managed to gather 12,000 cubic meters of fuel in the army zones, while 8,000m3 were on their way and 3,000m3 in reserve. The difficulty lay in getting the fuel to the units at the front. So, on the morning of the 17th, D+1, Kampfgruppe Peiper’s men were looking for gasoline: the supply trucks had not arrived. Peiper decided to deviate from the planned objective to take the village of Büllingen, where the Americans were said to have a fuel depot. The detour was quickly undertaken, U.S. opposition was minimal, and 227,000 liters of fuel were seized and emptied straight in the vehicle tanks. About an hour later, American artillery opened fire on the village. Peiper sent a small detachment north, which was quickly stopped by the 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Two Panzer IVs were destroyed while the others turned around.

This discouraged Peiper from this direction, especially as his orders were to advance southwest, which he did. He wanted to take Ligneuville as soon as possible, as he was hoping to surprise the staff of the 49th Antiaircraft Brigade. But the roads were in a disastrous state and the advance was too slow; in any case, General Timberlake and his staff had just enough time to escape from Ligneuville, ten minutes before the panzers entered the village.

Outside Ligneuville, the panzers clashed w...