![]() PART ONE

PART ONE![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Origins of Professional Archaeology

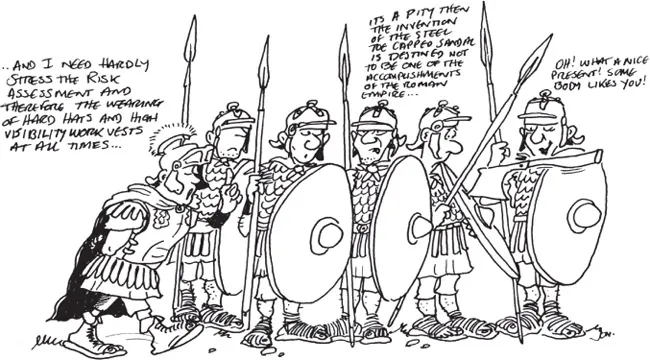

Figure 21: Origin of the risk assessment. © Jon Hall

Introduction

Much has already been written on the legislative, public and professional developments that have created contemporary commercial archaeology (eg Breeze 1993; Hunter et al 1993; Lawson 1993; Biddle 1994; Carman 1996; Chadwick 2000; Wainwright 2000; Carver 2011; Flatman 2011; Aitchison 2012). While this topic could form the focus of a research project in its own right, the history of commercial archaeology is outlined in this chapter in order to understand the background and nature of the ‘professional’ environment within which the subjects of this research are sited. The working lives of British contract archaeologists in 2012 are a direct result of the evolution of Rescue Archaeology and the shifting priorities of politicians, and this has produced complex and often contradictory narratives within the profession. This chapter aims to provide the reader with a sense of context, and an appreciation of why many of the participants have very individual interpretations of what it means to be a commercial archaeologist and why, therefore, personal expectations are often so different.

In format this chapter will deal separately with the legislative components of Ancient Monument Protection and the Town and Country Planning Acts, which led ultimately to the publication of PPG16 (Planning Policy Guidance, Note 16) in 1990. Despite being replaced initially by PPS5 (Planning Policy Statement 5) in 2010, and then by the NPPF (National Planning Policy Framework) in 2012, PPG16 established the key frameworks of commercial practice, and for this reason it is covered in more detail. MAP2 (The Management of Archaeological Projects [2nd Edition]), which was produced by English Heritage in 1991, is focussed on rather than its English Heritage successor document - MoRPHE (Management of Research Projects in the Historic Environment) - because of its impact on the evolution of developer-led archaeology. Alongside these sections ‘Rescue’ archaeology will be discussed from its amateur and research-led roots prior to the Second World War - through the radical changes initiated by the (re)development boom in the 1950s and 60s – to the emergence of commercial archaeology.

Ancient monument legislation

In 1882, following decades of concern over the condition of some of Britain’s archaeological and historical remains, the Ancient Monuments Protection Act became “the first conservation measure passed by the British Parliament” (Breeze 1993:44). An initial ‘schedule’ of 24 Monuments (John Schofield pers comm), located across Britain, formed an appendix to this Act and these subsequently came under State Guardianship – though remaining the property of private landowners. General Pitt Rivers was appointed as the first Inspector of Ancient Monuments in 1883 with a mandate to preserve, analyse and understand the archaeological remains in his charge (Pugh-Smith and Samuels 1996:6). Several Parliamentary Acts, culminating in the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979, have subsequently superseded the 1882 legislation, but the basis remains the same.

Under the terms of the 1979 Act the relevant Secretary of State (since 1997 this means the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport) is responsible for the Scheduling of Monuments of national importance in England. Since the devolution of some powers from Westminster in 1999 the Secretaries of State for Wales and Scotland no longer perform this role. Currently Cadw, established in 1984, undertakes these duties as the Historic Environment Division of the Welsh Assembly. Historic Scotland, created in 1991, performs the same role for the Scottish Executive (ie the Ministers of the Scottish Parliament). Since the creation of English Heritage in 1983 it has advised the relevant department (currently DCMS) on key issues including the Scheduling of Monuments and areas of archaeological importance. This also, significantly, includes the granting of Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC), which has to be obtained from the Secretary of State before any works that might damage or destroy the monument can be undertaken.

The Secretary of State may grant consent for the execution of such works either unconditionally or subject to conditions, or can refuse outright. The consent, if granted, expires after five years. Compensation may be paid for refusal of consent or for conditional consent in certain circumstances, in particular if planning permission had previously been granted and was still effective (Sections 7-9). Failure to obtain SMC for any works of the kind described in Section 2(2) is an offence, the penalty for which may be a fine which, according to the circumstances of the conviction, may be unlimited. Provision is made for the inspection of work in progress in relation to SMC (Section 6 (3), (4)). Successful prosecutions of parties who undertook works without consent or broke SMC conditions have occurred. (Breeze 1993: 48)

By January 2006, there were 17,700 Scheduled Monuments - covering some 36,000 archaeological sites - listed by the DCMS in England. There can be no doubt that the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979 and its predecessors have protected and preserved a lot that would otherwise have been lost to us. However, some commentators believe that when faced with real crisis the Act was essentially powerless (Biddle 1994), and that

After several decades of reaction to archaeological crises and escalating expenditure by central government on rescue archaeology, it was not the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 which solved the problems. Rather it has been the creation of English Heritage by the National Heritage Act 1983 and the publication of Planning Policy Guidance Notes “PPG 16” in 1990 and “PPG 15” in 1994 which have done more to safeguard the long-term future of archaeological remains in Britain. (Pugh-Smith and Samuels 1996: 7)

Planning legislation before PPG 16

Planning policy in Britain did not become a major concern for the Government until the rapid expansion of towns and cities following the industrial revolution created certain health issues. These problems were invariably related to the density of housing and in 1844 the Royal Commission on the Health of Towns published its first report. In 1848 two Acts were passed by Parliament that were to be the first of many relating to town planning. The first, the Public Health Act, set up local health boards in areas where the conditions were deemed unacceptable, either by the higher than average mortality rate or by a petition of local people. These local boards “were granted powers to ensure that both existing and new houses were provided with water and drainage” (Blackhall 2000). The second Act, the Nuisance Removal and Disease Prevention Act, made it a legal requirement for new housing that they should not rely upon open ditches for drainage. The Nuisances Removal Act 1855 extended this to the provision of adequate toilet facilities, drainage and ventilation in order to ensure that a house was suitable for human habitation. There were several more Acts in the late 19th Century that expanded on this theme of ensuring a lower limit for the quality of housing in order to deal with public health issues.

The first legislation to introduce modern town planning schemes was the Housing, Town Planning etc Act 1909. This enabled (or, in large towns, required) local authorities to create town-planning schemes that were subject to approval from the Local Government Board, or Parliament itself. These schemes “allowed the definition of zones in which only certain types of buildings would be permitted” (Blackhall 2000). This Act also incorporated and expanded earlier requirements for sanitation with regard to new housing.

The Town and Country Planning Acts

In 1932 Parliament passed the first of a long line of Town and Country Planning Acts. Significantly, it extended the concept of planning schemes to non-urban environments and to the redevelopment of urban areas. The Acts of 1943 and 1944 were concerned predominantly with the rebuilding of those areas badly damaged by the war, but by 1945 the thoughts of Government were focused on building a better Britain for its exhausted population. This led to the embracing of the concept of New Towns in the New Town Act of 1946 and the creation of Green Belts1 in the TCPA, 1947. In this modern vision for Britain, the population was to be decentralised from the overcrowded and war-ravaged urban centres and the spread of these areas was to be controlled to keep them discreet. Many young families were moved from London Boroughs to market towns in the South East under Town Expansion Schemes.

The Town and Country Planning Act 1947 repealed nearly all of the previous legislation. Planning decisions were removed from the shoulders of local authorities and centralised at a time when industries and utilities were also being nationalised. Central government implemented a system of town and country maps to be produced by local planning authorities. These were to use a standard system of scale, notation and colour coding and would demonstrate land use. For the first time the concept of planning ‘zones’ was abandoned in favour of ‘land allocation’, whereby the primary land use of certain areas is decided by the planners. It is, however, more flexible than the older system of ‘zoning’ as it does not rule out some secondary uses for the land (ie shops in residential areas). This system is still used in Britain today. The TCPA 1947 also took some rights away from individual landowners. It would no longer be possible for someone to develop on his or her own land without prior approval from the State. Furthermore those individuals who did not receive permission were not eligible for compensation, while those that did were required to pay in tax the difference between the value of their land before and after the granting of planning permission (known as the windfall gain).

The Planning Acts of 1953, 1954, 1959 and 1960 made minor amendments to the TCPA 1947 and all of this legislation was consolidated in 1962. However, the next significant Act was the TCPA 1968. The 1950s and 1960s had seen a period of extensive slum clearance and rehousing along with the increasing involvement of private developers in the redevelopment of town centres. The 1947 Act proved to be prohibitively slow in relation to the speed at which development was moving. The TCPA 1968 amended the twenty-year-old system of plan making and approval and installed a two-tier structure in some local authorities. Within the areas affected by this new legislation county councils were responsible for producing the broader plans as required by the TCPA 1947, which still required governmental approval. At the same time district councils produced more detailed and technically up-to-date local plans, which, significantly, required the participation and approval of local people. The Local Government Act 1974 created new metropolitan counties and the two-tier system of planning was extended to the whole country.

The incoming Conservative government of 1979 was keen to encourage developers and redevelopment and saw the current planning legislation as a significant barrier to economic progress. By 1986 the Government had introduced Enterprise Zones, Urban Development Corporations and Simplified Planning Zones, all of which were designed to assist in the redevelopment of run-down areas by removing large portions of the planning requirements. It had also abolished the development land tax (the windfall gain payable by landowners under the TCPA 1947) as a further encouragement to developers and by its abolition of the metropolitan county councils it removed a whole tier of planning requirements in the cities. It was during this period that the Government began trying to reduce local authority expenditure by encouraging private investment. For much of the 1980s “planning was ‘developer led’ because of the government’s determination that private investment should not be stifled by the planning system. Where local planning authorities refused planning permission, their decisions were frequently overruled by the then Secretary of State” (Blackhall 2000). However, it would be a shift in government policy towards a tightening of planning controls at the end of that decade that would eventually lead to the creation of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and the Planning Policy Guidance Notes (PPGs) that were associated with it.

Archaeology before PPG 16

From research to RESCUE

Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War archaeological fieldwork was almost invariably an academic exercise. Whether or not it was ‘institutionally’ academic the act of excavation was designed to recover objects or, later, to answer specific research questions. So-called ‘Rescue’ archaeology in this period was often just a matter of retrieving artefacts and bones once the contractors had excavated their trenches. “The research worker or the good amateur archaeologist was usually too engrossed in his particular problems to watch building sites or to undertake an excavation of a site for no better reason than that it was going to be destroyed” (Rahtz 1974).

The war saw two very important changes within archaeology. Firstly the widespread construction of large defence installations, such as airfields and other bases, brought the destruction of archaeology by development to the attention of the government, which was required to act under Ancient Monument legislation. 450 airfields had been constructed on 300,000 acres of land and 55 Research excavations had been financed as part of the process (Wainwright 2000). Secondly, with more important things to deal with, research excavations were largely curtailed. The result was that government-sponsor...