eBook - ePub

Harmony and Discord in Africa

Memories of Childhood in Southern Rhodesia

Mark Huleatt-James

This is a test

Share book

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Harmony and Discord in Africa

Memories of Childhood in Southern Rhodesia

Mark Huleatt-James

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In 1949, newlyweds Tom and Angela Huleatt-James left war-torn Europe for a new life in Africa. Fleeing the grey skies of post-war Britain, they were attracted to the idea of farming in Southern Rhodesia and determined to work there for a better future. In this book, their son Mark tells the story of their adventures in Africa and his childhood and education in Southern Rhodesia. This was the time when European hegemony in the area was at its zenith. The difficult years of the Great Depression and World War II were over and an agricultural and commodities boom was under way. Mark Huleatt-James details his memories of being a young child in this period - from a love of wildlife to the social life enjoyed by Europeans at the time.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Harmony and Discord in Africa an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Harmony and Discord in Africa by Mark Huleatt-James in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Colonialisme et post-colonialisme. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

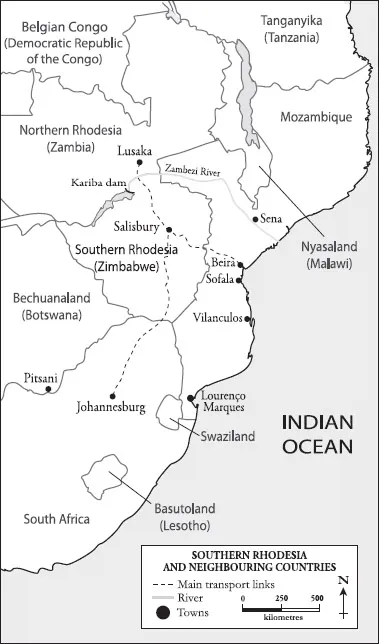

Map 1 Southern Rhodesia and neighbouring territories

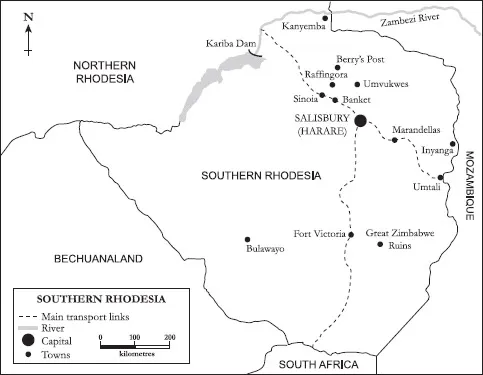

Map 2 Southern Rhodesia

1

INTO AFRICA

England, after all the exertion and adrenaline of World War II, was not the most exciting place in which to live. Life there was fairly accurately summed up in the phrase ‘ruins, rationing and reconstruction’. Furthermore, England’s weather remained obstinately and greyly English. For many people, especially servicemen returning from foreign parts, the allure of life in the colonies, particularly those colonies in the sunny tropics, grew ever stronger the longer they were home.

My parents had married in October 1948 and had decided that their future life together should be on a farm where they could be close to each other, have children and work for the common good of the family. The question of the moment was where this idyll should be located. My parents were clear about one thing and that was that it was going to be out of England. They were, nevertheless, determined to remain British and in the British Commonwealth, even if they did not remain in Britain.

They opened an atlas of the world and did a trawl through all of the pink bits on the maps. They had little by way of personal contact with any of them. The list of countries in which they might find the home of their dreams was soon whittled down to just two: New Zealand and Southern Rhodesia. The merits of each, to the extent that my parents were aware of them, appeared to lie evenly in the balance. My mother eventually decided on the latter for the reasons that she had heard that its weather was good and she preferred its postage stamps. Those were good enough reasons for my father.

Though my father had neither a job nor a farm in Southern Rhodesia, my parents had some of their furniture crated up to be sent out to Salisbury, the capital. For themselves, they bought tickets to Cape Town on a Union Castle Line steamer, with an onward booking for the train from Cape Town to Salisbury. On their way to catch the boat to Cape Town they passed through London. As they were going over Westminster Bridge in a taxi they overtook a lorry and saw that it had a large crate on it labelled ‘HULEATT-JAMES/SALISBURY’. They took this as an auspicious omen. Their possessions were clearly on their way to Southern Rhodesia. Whatever lay ahead for my parents in Southern Rhodesia, they felt that at least they would have a bed to lie in.

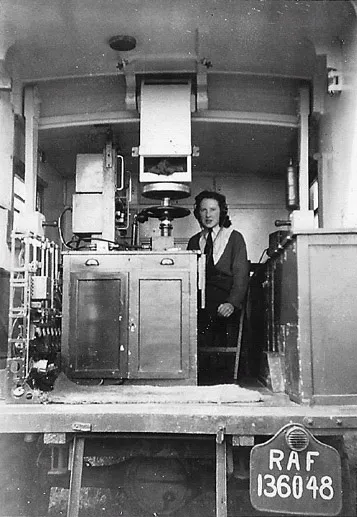

Until their departure for Africa, this young couple’s experience of life had given them every reason to be optimistic. Things had generally worked out reasonably well for them. In 1943, after leaving school in the Irish Free State at the age of eighteen, my mother travelled to England and joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Given her aptitude for maths, she was posted as an operator of a fixer station, tasked with re-orientating disorientated pilots (who did not then have the luxury of GPS and for much of the time had to keep their eyes on the enemy rather than the map). Being a passionate horsewoman she refused to stay in Air Force billets, but found herself accommodation with landlords who had horses in need of exercise. This, along with occasional forays into London and its social scene, had the result that she spent her two years of war service much more agreeably than most.

My father was a month older than my mother. He also left school at eighteen, and joined the navy. He spent most of his war service in small boats on the Mediterranean Sea and the English Channel. Some of his service was in mine-laying ships, an exhilarating experience because they were extremely fast, enabling the crew to scoot off home once they had deposited their cargo of mines along the enemy coast. Fortuitously, his presence was not required in the vicinity of the Normandy beaches until the day after the D-Day landings. The Mediterranean, while he was there, was not the most arduous theatre for naval warfare.

Figure 1 My mother, Angela, in her fixer station

My parents were also both suited by disposition to taking a step into the unknown and living in amongst people with unfamiliar backgrounds. My mother was a robust, friendly woman with a ready sense of humour, not so much of the drawing room kind, but which really came into its own when the wheels started falling off things. She was not afraid to look ridiculous. She judged people not by label or appearance but for what they really were. When she was in London during the war, she continued to visit a favourite aunt by marriage, Aunt Margaret, who was German. What is more, she was a German with an awkward, though not unconscionable, connection, being a close friend of Ludwig von Reuter and the godmother of his son. Von Reuter was the admiral who, in June 1919 and to the fury of the British naval high command, scuttled the German High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow, the Orkney Islands. Though my mother was capable of expressing her views with some candour, I never heard her utter a bitter word.

Figure 2 My father, Tom, as a fresh-faced midshipman just out of school

Not having my mother’s computational ability, my father navigated life, the seas and the Rhodesian bush as much by instinct as by calculation. He was practical, good with his hands, gregarious and impetuous. Life’s absurdities tickled him enormously.

Even though Southern Rhodesia was a British colony, my parents were to find that there was little that was really British about the place. Colonial democracy was not the same as the Westminster model, as practised in Westminster. The culture and language of the Africans (who outnumbered Europeans by about twenty to one) was unlike anything they had experienced in Britain. The attitudes of Europeans who had already been in the country for several decades were also fairly foreign. In addition to that, the physical environment, fauna, flora, weather and approaches to farming bore almost no resemblance to their British counterparts. Much of this had the attraction of novelty, whilst at the same time containing dangers which were not immediately apparent.

After spending a morning in Cape Town and taking the cable car up to the top of Table Mountain my parents were in high spirits. Cape Town has every right to claim that it is situated in the most strikingly picturesque location in the world. From Table Mountain my parents could see the long sandy beaches of Sea Point and False Bay. In the distance were rugged mountains footed, so they were told, with fine vineyards. Turning round, they could admire the long finger of the Cape of Good Hope stretching down toward the Antarctic. The Cape area and, by imaginary extension, the rest of southern Africa looked a pretty fine place.

That evening, and full of good hope, my parents boarded the train to Salisbury. It was to be a long journey of several days through the Karoo (they had yet to discover that this was the Khoisan word for ‘land of thirst’), Bechuanaland (Botswana) and much of Southern Rhodesia. The next morning, looking out of the train windows, they were very surprised and alarmed to see mile after mile of sand and scrub. Such research as they had done had not unearthed any desert in the vicinity of their new homeland. Bechuanaland’s landscape was a little, but not a lot, better. It was night-time when the train eventually puffed its way up into Southern Rhodesia, with the result that my parents had no way of establishing whether the habitability of the countryside had improved.

The train pulled into Salisbury station early in the morning on 1 April 1949. After the somewhat unsettling revelation on the first morning of their train journey, the significance of the date was not lost on my parents. They disembarked and then went to round up their luggage, all twenty-seven pieces of it. That accomplished, they were met by a Mr Peyton, to whom they had an introduction. He bore bad news. There was a Bethlehemian shortage of hotel accommodation in Salisbury.

Many other European people, coming not only from the United Kingdom but also from countries which had fallen within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence, had had similar ideas to those of my parents and had arrived in Southern Rhodesia at much the same time. In 1948, the number of European immigrants totalled nearly seventeen thousand, and in 1949 it was not much less (these were significant inflows given that the African population of the country at the time was a little more than one and a half million and it stood at a ratio of twenty to one against that of the Europeans). They all needed accommodation and the hotels were unable to cope. Quite bizarrely, the government decided to deal with the problem by decreeing that no-one was to be allowed to spend more than five consecutive nights in the same hotel. After that they had to take their chances with the next hotel or whatever alternative accommodation might be available.

The only accommodation that Mr Peyton had been able to find which was immediately available was in the St Vincent de Paul hostel for the destitute. He had, fortunately, booked them a room in Meikles Hotel for five nights in the following week. Meikles was a stylish colonial hotel, generally thought of as the best in Salisbury, which not only provided accommodation but also served as a meeting point for people, particularly farmers, coming from the country for a day in Salisbury. It had a large lounge with deep crimson carpets and comfortable chairs with plush cushions. Friends and acquaintances from different parts of the country would meet there for a light lunch or a sun-downer, and gossip. Its head-waiter, Snowball, was a recognised authority on what was going on in the horse racing world and punters would press him for tips with tips of their own.

My parents moved from Meikles to the Grand Hotel and from there to the Windsor Hotel and then back to Meikles (they were left wondering how the Grand Hotel had ever acquired its name). Such were the ups and downs in the lives of new arrivals. Fortunately for them, they did not have to endure this farcical merry-go-round for more than a couple of weeks because a friend of one of their contacts asked them to look after his large and comfortable house while he went away on six weeks’ holiday.

Employment was now a priority for my father, but as it was not going to come looking for him he would have to go out and find it. In that search he would get little assistance from the local public transport system, which scarcely existed. He bought an old Ford V8 truck, large enough to accommodate himself, his wife and the twenty-seven pieces of luggage. The commercial farms on which he was seeking employment were to be found on the Rhodesian Highveld. As its name implies, this was the higher ground (between 4,600 and 5,500 feet) in the centre of Southern Rhodesia which sloped gently down from north-east to south-west. Huge areas of lowveld, in the south-east and north-west of the country were unpleasantly hot and disease-ridden and therefore not really practicable from the point of view of agriculture.

As soon as he could drive, my father had developed a love of large, fast cars. He also had a brief flirtation with motorbikes, but after a budding romance was cut short when he started off too quickly, with the result that his girl fell off the back of the bike, leaving her skirt behind on its rear number-plate, he decided to stick to four wheels. He tuned those cars up and did the maintenance on them. The expertise that he acquired enabled him to get, for those times when he was not on the trail of a possible job, work in a garage fixing cars.

My father’s uncle, Terry Schreiber, had provided him with a letter of introduction to Winston Field, who owned a farm near Marandellas, some forty-five miles to the east of Salisbury. Winston Field was later to become, albeit for only a brief period of time before he was displaced by Ian Smith, the prime minister of Southern Rhodesia. The Fields invited my parents to spend the weekend with them at their farm. They were generous hosts. After a very alcoholic evening Winston arrived in my parents’ room, at five-thirty in the morning, bearing two trays on each of which two foaming glasses were offered; one was gin and tonic (by way of ‘hair of the dog’) and the other was Alka-Seltzer – providing the hung-over guest a choice of remedy. But they could not offer any work.

Their next introduction was to General Higginson who lived in the Umvukwes area, fifty miles north of Salisbury. He had presumably been a fighting general because he only had one leg. He pointed my father in the direction of a nearby estate, Frogmore, which had recently changed hands and, he suggested, could be in need of an assistant manager. It was, and my father was appointed as assistant to the general manager, Ian Hale. My mother, with her good head for figures, was employed as the estate bookkeeper.

The Umvukwes was an area of dry miombo (a type of African tree) and scrub woodland on which were scattered a profusion of kopjes (great piles of large granite rocks interspersed with trees and scrub) and, here and there, huge dome-like granite protrusions. In the dry season, in particular, it offered a spectacularly colourful palette of yellow grass, green trees, grey rocks flecked with red lichen and, more often than not, clear blue skies. In the wet weather, November to April, the countryside turned green and the clouds piled up high in the sky, dark and heavy. Isolated clumps of tall gum trees, the bark peeling from their enormous grey trunks, usually signified the presence of a European homestead nearby.

The rock overhangs and shelters on many of the kopjes retained vestiges of prehistoric habitation. For millennia, San hunter-gatherers had roamed over the countryside before being displaced by the darker-skinned Bantu tribesmen who had started to migrate south from the bush and forest country of sub-Saharan West Africa about two thousand years ago. It is thought that the Bantu arrived in the area which is now Southern Rhodesia in the seventh century. The San retreated before them into the arid, semi-desert areas of south-western Africa, areas which could support small families of hunter-gatherers but not tribal groups with cattle. But the San did leave behind them a huge quantity of paintings on the rock walls and roofs of their caves and shelters in the kopjes. Visiting any kopje you were as likely as not to come across a painting. Some of the paintings were thousands of years old and depicted, for the most part, animals and animal hunts. But many contained fascinating symbolic elements and patterns which, even to this day, are little understood.

My parents were given the old main farmhouse to live in, a gesture which was not quite as generous as it at first seemed. The previous male occupant had, in the course of some very acrimonious matrimonial dispute, shot his wife and then himself. There had been blood everywhere, not all of which had been removed by the time that my parents arrived. Ian Hale, on the other hand, lived in a large and gracious house that had been built by Italians held in Southern Rhodesia as prisoners of war.

Frogmore was a professionally run large-scale commercial agriculture operation. There were six other houses being built on the place to house the extra staff needed. My parents were soon lucky enough to be invited to move into one of these houses and thus make their escape from the ghoulish environment of the old main farmhouse. But even with this new house all was not perfect because, for some strange reason, the architect had not provided the house with any internal corridors. All the rooms radiated off the living room. External access was limited to a front door leading directly into the living room and a back door to the kitchen. If my mother was working in the kitchen she could not get to her bedroom without going through the living room. So if she wanted to tidy herself up for a visitor who had arrived unannounced, as they often did, she had to go out through the kitchen door and then climb in through the bedroom window in order to do so.

My parents stayed on Frogmore for two years and it provided my father with a solid training in tropical agriculture. It also provided him and, to a lesser extent, my mother with a chance to get to know and work alongside the black Africans in the area; to find out a little about who they were and what made them tick. They were primarily Mashona from Southern Rhodesia, but many of them came from Mozambique, Northern Rhodes...