![]()

Chapter I

The World into which Confucius Came

China Before Confucius

In this section, I will consider the intellectual and religious context that shaped the thought world into which Confucius was born and how he expressed this worldview in his teachings. I begin by noting that Confucianism was born into one of the great ‘cradles of civilization’. As far back as the Neolithic period, features that we recognize as belonging to Chinese culture had already appeared in China: pat-rilineal descent, use of ritual objects, social hierarchy and elaborate burial procedures (Van Norden 2002a: 4).2 Ancient Chinese history is traditionally said to have begun with three sage-kings: Yao, Shun and Yu and the ‘Three Dynasties (san dai)’. The Three Dynasties are the Xia, the Shang and the Zhou. Although its findings are still very controversial, the Xia Shang Zhou Historical Project (Xia Shang Zhou Duandai Gongcheng) was commissioned in 1996 by the People’s Republic of China and gave its report in 2000. The report held that the Xia dynasty was real and not merely legendary and that its probable time span using a Western calendar was 2070–1600 BCE; that the Shang should be divided into an early phase (c. 1600–1300 BCE) and a later phase (c. 1300–1046 BCE); and that the Zhou dynasty was the most well documented of the three, extending from 1040 to 771 BCE.

The Zhou dynasty was founded by a family with the surname Ji (姬) and centered on the region of Haojing, located in Western China near present-day Xi’an. In 771 a civil war about proper succession to the throne culminated in the movement of the capital eastward to Luoyang in modern Henan province and resulted in what is known as the Eastern Zhou dynasty (c. 770–221 BCE). This period is typically divided into the Spring and Autumn Period (Chunqiu Shidai, c. 722–481 BCE) and the Warring States Period (c. 480–221 BCE). The Spring and Autumn Period was basically a set of feudal-type kingdoms with a weak center at the capital in Luoyang and correlated with the reigns of the dukes of Lu. The period of the Warring States (see Figure 1) ended with the unification of China by the ruler of the state of Qin, Qin Shihuang (personal name Ying Zheng, 259–10 BCE), who is also known as the First Emperor of China.3

Figure 1: The Warring States Period

Confucius often mentioned favorably the founder of the Zhou dynasty King Wen (a.k.a. Zhou Wenwang, birth name Ji Chang, 1099–50 BCE), and his son, who was actually the commander who defeated the Shang dynasty forces, King Wu (Zhou Wuwang, birth name Ji Fa, r. 1046–43 BCE). However, Confucius had an even greater admiration for the Duke of Zhou (Zhou Gong, birth name Ji Dan). Confucius appreciated the Duke of Zhou’s administrative effectiveness and his humaneness. Once, when speaking of his own situation, Confucius said, ‘How I have gone downhill! It has been such a long time since I dreamt of the Duke of Zhou’ (Analects 7.5). The story that is most famously celebrated as an example of the Duke of Zhou’s great-heartedness is his care for his nephew, the crown prince of the Zhou. The Duke of Zhou was a younger brother of King Wu, and when Wu died soon after the conquest of Shang, the throne passed to King Cheng (Zhou Chengwang, birth name Ji Song, r. 1042–21 BCE), who at that time was only a minor. The Duke of Zhou administrated the kingdom as regent and faithfully passed Cheng a good and harmonious kingdom when he became of age. He did not try to usurp the throne or eliminate his nephew.

Another tradition explaining the respect and admiration shown toward the Duke of Zhou by Confucius and countless generations of Chinese insists that it was he who explained why the Shang dynasty should be overthrown. In this account, the Duke of Zhou is credited with revealing the concept of the Mandate of Heaven (tianming). According to this concept, Heaven (tian) brought to power rulers and kingdoms to care for the people. As long as those rulers followed the Way (Dao) of Heaven, ruling justly and providing for the people, they would be blessed by Heaven and could continue to rule. However, if the kings became corrupt and oppressed the people, the Mandate (authorization to rule) would be withdrawn and Heaven would choose a new ruling dynasty to overthrow the corrupt one. The doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven became a fundamental principle in Chinese political thought for almost 3,000 years and it is used to explain changes in dynasties. Floods, famine, disease and troubles were regarded as warning signs that the loss of the Mandate was imminent.4 The Duke of Zhou explained to the people of Shang that if their rulers had not misused their power, the Heavenly Mandate would not have been taken away from Shang and given to Zhou.

For our study of background to Confucius and the rise of Confucianism, the two sub-periods of the Eastern Zhou, the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, are of extreme importance because Confucius lived during the Spring and Autumn Period, and the classical movements and texts of Confucianism were first formed during the Warring States Period. Confucius did not create his thoughts in a vacuum and a number of early materials, including poems, ritual instructions, historical documents, religious and philosophical ideas, folklore and customs, influenced Confucius’s thought. A great deal of work has been done on reconstructing the ideas, practices and everyday life of Warring States of China in particular.5

The Ru and the Six Arts

Confucius stood within the tradition of scholars called Ru (儒). In the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), two centuries after Confucius’s life, Liu Xin (46? BCE–23 CE) says the Ru first appeared as an identifiable professional group in the early Zhou dynasty. They were noted for their allegiance to the sage-kings of ancient China, who followed the Way (Dao) of Heaven, and to the social, religious and moral rituals (li, 禮) of the distant and idyllic past when humaneness (ren, 仁) and moral righteousness (yi) prevailed. The History of the Former Han (Ban 2007: 1728) says that the function of the Ru was to follow the Dao of yin and yang and enlighten the people by education (1728). Liu Xin tells us the Ru were devoted to the ‘Six Classics’ (Liujing) and took Confucius as their master teacher. Of course, the late date of Liu Xin’s account makes this comment about Confucius somewhat open to debate, and it probably represents an attempt to reconstruct history at a time when the Han literati were developing the texts that would form the core of the intellectual substance of their culture for generations to follow, even down to the present day.

The Han dynasty association of Confucius with the Ru in such great specificity has been questioned.6 However, the first use of the character Ru in classical texts now in our possession is in the Analects, which is also the primary source for Confucius’s teachings. In that text, he tells his disciples to be a Ru of an exemplary person (junzi ru), but to avoid being a Ru for a petty person (xiaoren ru) (Analects 6.13); it seems likely, all things taken together, that Confucius does stand in the tradition of the Ru.7 If we see him as an extension of the Ru, we will better understand the snapshot we have of his teachings and practices in the Analects. Even though we may associate Confucius with the Ru, we should not think that the type of service given by the Ru and the nature of their work remained fixed from the time of the Shang dynasty through the Zhou, nor that all Ru performed or mastered each and every task performed by other Ru. However, having said this, a general description of the kinds of things Ru taught as a group may help us understand Confucius. They were specialists in:

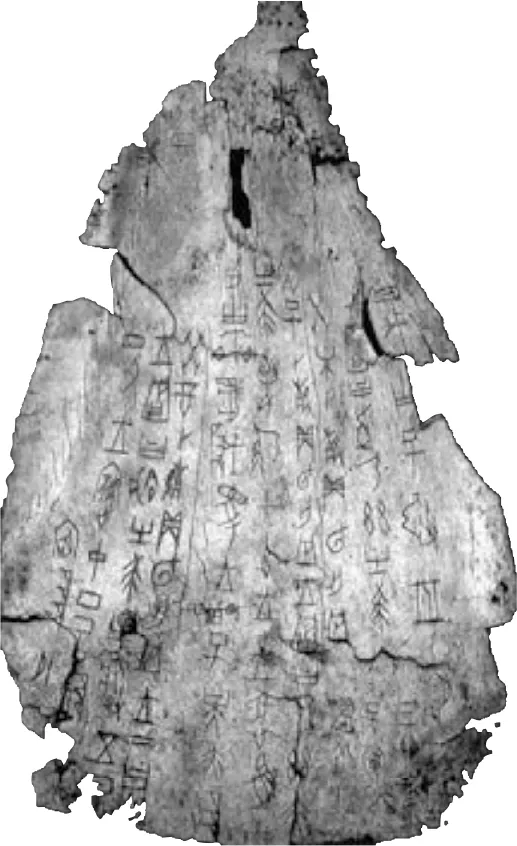

• religious rituals and political ceremonies, as well as divination probably using milfoil stalks (shizhan) by the time of the Zhou and perhaps by Turtle Shell Oracle Bone (jia gu) before the Zhou;

• communication with spirits (shen), including ancestors;

• practicing astrology (qizheng), calendrics (dunjia) and geomancy (kanyu jia);

• dance and performance;

• music;

• archery;

• poetry.

Figure 2: Oracle Bone Inscription

Surely not all Ru were skilled in all of these specialties, and Confucius seems not to have been a practitioner of some of them. By the time of the Spring and Autumn Period, the Ru masters principally made their living by conducting rituals, acting as consultants to rulers and officials, working with ancient texts and teaching private students who came their way. This sort of Ru profession included Confucius and it continued through the Warring States Period. Toward the end of that period, Han Fei (280?–33 BCE) observed that the two most famous schools of learning in his day were the school of Master Mo (Mozi, 470–391? BCE), known as the Mohists (Mojia), and the Ru, the most prominent figure of which was Confucius (Liao 1959: 2:298). Prior to the time of the Han dynasty, Ru had no systematic teaching or religious practice. In fact, we can understand the collection of Confucius’s own teachings in the Analects as part of just such an effort. With the elevation of the status of Confucius in the Han dynasty, ‘the teaching of Confucius’ (Kong jiao) became substituted for ‘the teaching of the Ru’ (Ru jiao) and took its place alongside ‘the teachings of the Dao’ (i.e., Daoism) (dao jiao) and other schools.

According to Liu Xin, the Ru practiced ‘the Six Arts’ (liu yi) or ‘the Six Forms of Learning’ (liu xue), with one of each embodied in the ‘Six Classics’ (liu jing) of the Ru. This connection between Confucius and the Six Classics is quite important in Chinese history and it is made earlier than Liu Xin. Actually, the Daoist work Zhuangzi uses an argument against Confucius in its ‘Yellow Emperor’ (Huang-lao) textual stratum (dating between 300 and 168 BCE), according to which Confucius comes seeking help from Laozi (the Daoist master) because no king or ruler will follow his ‘Six Classics’.8 The art of ‘the Way of Heaven’ that Confucius treasures seems to have been expressed in these Six Classics of the Ru.9 The Han dynasty scholar, Dong Zhongshu, called on the government to set aside all other arts than these six (Ban 2007: 2523). The role of texts is significant in Confucianism. In fact, we may say that Confucianism is unlike Daoism in being a tradition of books, not lineage masters; transmission, not inspiration; and commentary, not numinal experiences. Later, when Daoists wrote down their traditions, they did so largely as an imitation of Confucianism. Writing and producing texts was not originally part of the Daoist way. Daoism was a master– disciple, lineage transmission, of acute numinal experiences and the practices relevant to producing them.

The Six Classics associated with the Ru are these:

• the Classic of Poetry;

• the Classic of History;

• the Classic of Rites;

• the Classic of Music;

• the Classic of Changes;

• the Spring and Autumn Annals.10

Just what these texts were like in the time of Confucius is not presently determinable. The reason for this is that the ruler of the Qin dynasty, also known as the First Emperor of China, in an effort to unify his empire and solidify his power, ordered the horrific actions of ‘Burning the Books and Burial of the Scholars’ (Fengshu Kengru) in 213 BCE. According to the Records of the Historian (109–91 BCE), written and collected by Sima Qian (c. 145 BCE–6 BCE), only books concerning medicine, agriculture and divination were spared. All of the Six Classics were targets of this destructive policy. After the fall of the Qin, Han dynasty rulers commissioned remaining scholars to reformat the Six Classics. The Classic of Music seems to have been the one classic that was virtually irretrievable; we are unsure of its actual contents beyond what survives in the Classic of Rites and the Chronicles of the Zuo. It is clear to textual scholars now that new material was introduced to the reformatted versions of the now remaining Five Classics (Wujing) by the Han scholars. So, determining just which passages go back to the time of Confucius and before is not completely within our present ability to decide. Even so, we can take note of the contents of the Five Classics and have confidence that there is a substantial amount of material in them that is traceable to Confucius’s era.

The Classic of Poetry (also called the Book of Songs)11 contains 305 poems dating from about 1000–600 BCE, divided into three sections according to genre (i.e., folk songs (guo feng); minor festival songs (xiaoya) and major festival songs (daya); and religious hymns and eulogies (song)). The Classic of Poetry was well known to Confucius, and Sima Qian says in the Records of the Historian that he was its editor, reducing 3,000 poems to 305....