eBook - ePub

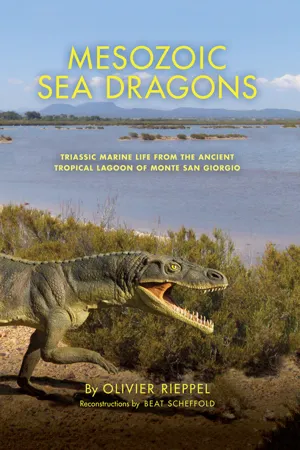

Mesozoic Sea Dragons

Triassic Marine Life from the Ancient Tropical Lagoon of Monte San Giorgio

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mesozoic Sea Dragons

Triassic Marine Life from the Ancient Tropical Lagoon of Monte San Giorgio

About this book

An extensive, illustrated study of the ancient fish and marine reptiles who once lived in a tropical lagoon that is now a Swiss mountain.

Told in rich detail and with gorgeous color recreations, this is the story of marine life in the age before the dinosaurs. During the Middle Triassic Period (247–237 million years ago), the mountain of Monte San Giorgio in Switzerland was a tropical lagoon. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site because it boasts an astonishing fossil record of marine life from that time. Attracted to an incredibly diverse and well-preserved set of fossils, Swiss and Italian paleontologists have been excavating the mountain since 1850.

Synthesizing and interpreting over a century of discoveries through a critical twenty-first century lens, paleontologist Olivier Rieppel tells for the first time the complete story of the fish and marine reptiles who made that long-ago lagoon their home. Through careful analysis and vividly rendered recreations, he offers memorable glimpses of not only what Thalattosaurs, Protorosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Pachypleurosaurs, and other marine life looked like but how they moved and lived in the lagoon.

An invaluable resource for specialists and accessible to all, this book is essential to all who are fascinated with ancient marine life.

Praise for Mesozoic Sea Dragons

"The most comprehensive review of the Middle Triassic marine faunas of Monte San Giorgio published to date. It synthesizes a vast body of literature in an accessible way and provides an informative, beautifully illustrated review of the vertebrate life that once thrived in the ancient lagoon. It also delivers a fascinating account of the history of fossil discoveries of this remarkable site." — Palaeontologia Electronica

Told in rich detail and with gorgeous color recreations, this is the story of marine life in the age before the dinosaurs. During the Middle Triassic Period (247–237 million years ago), the mountain of Monte San Giorgio in Switzerland was a tropical lagoon. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site because it boasts an astonishing fossil record of marine life from that time. Attracted to an incredibly diverse and well-preserved set of fossils, Swiss and Italian paleontologists have been excavating the mountain since 1850.

Synthesizing and interpreting over a century of discoveries through a critical twenty-first century lens, paleontologist Olivier Rieppel tells for the first time the complete story of the fish and marine reptiles who made that long-ago lagoon their home. Through careful analysis and vividly rendered recreations, he offers memorable glimpses of not only what Thalattosaurs, Protorosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Pachypleurosaurs, and other marine life looked like but how they moved and lived in the lagoon.

An invaluable resource for specialists and accessible to all, this book is essential to all who are fascinated with ancient marine life.

Praise for Mesozoic Sea Dragons

"The most comprehensive review of the Middle Triassic marine faunas of Monte San Giorgio published to date. It synthesizes a vast body of literature in an accessible way and provides an informative, beautifully illustrated review of the vertebrate life that once thrived in the ancient lagoon. It also delivers a fascinating account of the history of fossil discoveries of this remarkable site." — Palaeontologia Electronica

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mesozoic Sea Dragons by Olivier Rieppel,Beat Scheffold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Marine Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Marine BiologyThe Dragon Mountain

1

Bernhard Peyer

It had been a hot day, in spite of the surrounding trees, which offered speckled shade. But the team of paleontologists had managed to clear another slab of Triassic fossiliferous sedimentary rock from the overburden. In the oblique light of the late afternoon, the contours of several promising fossils could be made out—some fish, several other small, lizard-like pachypleurosaurs. No larger fossils were found that day. They had circled the fossils with white chalk lines and planned to cut them out the next day. Then they would further expand their dig in the following days and weeks, when they would hit it big! The find would be a complete skeleton of a new lariosaur genus and species, 104 cm in total length (small by comparison to other, later finds of the same species), which Peyer christened Ceresiosaurus calcagnii, in honor of Commendatore Emilio Calcagni (Peyer, 1931a). Calcagni was the landowner who had graciously allowed excavations to proceed since the spring of 1927, when Peyer first found fossils at this locality. Peyer derived the genus name, Ceresiosaurus, from the local name for Lake Lugano, which embraces the eastern, northern, and western flanks of the northward-jutting pyramidal mountain; the team was working on the western slope of this mountain, some way above the Italian lakefront town of Porto Ceresio. Satisfied with the dig’s progress, Peyer poured himself a strong coffee, espresso really, from his Thermos flask. To complete what he called the trimming of a fossil find, the coffee was to be accompanied by a shot of Grappa del Ticino, a spirit distilled from pomace of Merlot, the signature grape of the Canton Ticino, Switzerland.

Peyer sat down and proceeded to stuff his pipe, looking at his crew of workers through his rimless spectacles. Absent-mindedly, he picked up a chestnut, one of the first to have ripened this season. The Ticinesi, the local inhabitants of the Canton Ticino, collect them in the fall to roast over fire or glowing charcoal. Some would travel to northern cities in Switzerland—Lucerne or Basel—to sell their freshly roasted Marroni on the streets. With all the excitement of fossil hunting, Peyer had not realized how hungry he was. He looked forward to ordering braised rabbit with polenta for dinner at the local Grotto, the Ristorante Alpino in Serpiano, paired with a bottle of the local Merlot, and followed of course by another trimming—an espresso con grappa (Kuhn-Schnyder, 1968)! It was late summer of 1928, and his team was fossil hunting at the Acqua del Ghiffo locality near Crocifisso (fig. 1.1), on Monte San Giorgio, the latter located in southern Switzerland just across the border from Italy.

Peyer had a lean, wiry physique and was wearing baggy trousers stuck in rubber boots. During the heat of the day he had taken his jacket off and put it aside, but being the only academic on the site, he had thought it proper to keep his vest on. His hair, currently disheveled, was cut short and combed to one side. As Peyer stroked his moustache, which partly obscured his thin lips, he thought it needed trimming. Bernhard was born in the Swiss town Schaffhausen on July 25, 1885, son of the textile manufacturer Johann Bernhard Peyer and his wife, née Sophie Frey (H. Fischer, 1963; H. C. Peyer, 1963). The parents guided their son Bernhard through the Schaffhausen school system toward graduation in a classical humanistic education. Bernhard displayed a mastery of foreign languages—and these included not just French, English, and Italian but also Latin and classic Greek. One of his preferred leisure-time activities became reading and reciting Homer, author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, in the original. But Bernhard felt equally at ease in the outdoors and developed an early interest in natural history, paleontology, and geology. He obtained his first formal training in zoology and comparative anatomy as a student of Arnold Lang (1855–1914), a former student, then assistant, and eventually colleague of the famous Jena zoologist and evolutionist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), also known as the “German Darwin.” Of Swiss extraction, Lang joined the University of Zurich in 1889, where he pursued a stellar career until his death in November 1914 (Haeckel, Hescheler, and Eisig, 1916). Peyer (fig. 1.2) studied further at the University of Munich, where he heard the famous zoologist Richard Hertwig (1850–1937), another Haeckel student, and forged relations that would evolve into longtime friendships with the paleontologists Ferdinand Broili (1874–1946) and Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach (1871–1952).

Back at the University of Zurich, Peyer obtained his PhD under Arnold Lang with a dissertation on the embryonic development of the skull of the asp viper, Vipera aspis, a venomous snake native to central and southern Europe, a species first described by Linnaeus in 1758. Karl Hescheler (1868–1940), former student and eventual successor of Arnold Lang as professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Zurich, encouraged Peyer to apply for the venia legendi—the honor and duty to teach at the university level—with the submission of his work on the fin-spines of catfish as a Habilitation thesis. Hescheler is considered the initiator of Swiss paleontology, not only through his research on fossil mammals but also as a founding member of the Swiss Archeological and Paleontological Societies. A bachelor throughout his life, Hescheler bequeathed his estate to the University of Zurich, thus establishing the Karl Hescheler endowment. The latter would support Peyer’s paleontological excavations in important ways in the years to come and continues to support the Zoological and Paleontological Museums of the University of Zurich to the present day.

On the excavation in 1928, Peyer was still a lecturer at the University of Zurich, but in 1930 he was promoted to associate professor. In 1943 he was voted full professor of paleontology and comparative anatomy, and director of the Zoological Museum of the University of Zurich. During his long and extraordinary career, Peyer published extensively, producing numerous voluminous monographs on the Triassic reptiles from Monte San Giorgio and also on fossil remains of sharks, bony fishes, reptiles from other localities and time horizons, and important papers on fossil mammals, most notably the Late Triassic haramiyids from Hallau near his home town Schaffhausen (Peyer, 1956). He also published on the development and histology of vertebrate hard tissues, especially teeth. But additionally he contributed publications in the history of science, such as comments on the biological writings of Aristotle; a biography of his famous forefather, the medic Johann Conrad Peyer (1653–1712); an account of the biological writings of the medic Johannes von Muralt (1645–1733); a portrait of the senior town physician and polymath Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672–1733) from Zurich; an aperçu of the founding father of stratigraphy, Nicolaus Steno (1638–1686); and an overview of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749–1832) vertebral theory of the skull. When he happened to observe the exotic reproductive behavior of the large land slug Limax cinereoniger during fieldwork at Monte San Giorgio in the years 1927 and 1928, he published that too, together with his field assistant, the student Emil Kuhn.

1.2. Bernhard Peyer (1885–1963), date unknown (Photographer unknown; digital rendition Heinz Lanz).

1.3. (top) and 1.4. (bottom) The little town of Meride in 2000 (Photo © Heinz Furrer/Paleontological Institute and Museum, University of Zurich); Via Bernardo Peyer, Meride, March 18, 2001 (Photo © Heinz Lanz/Paleontological Institute and Museum, University of Zurich).

Near the site of Peyer’s excavation was Meride, a small, historic municipality located at the southern foot of Monte San Giorgio (fig. 1.3). The houses are grouped along the main street that stretches from east to west along the side of the mountain, forming the backbone of the village. In its center stands the church San Rocco, dating from the seventeenth century. On slightly elevated grounds west of the village is the church San Silvestro, dating from the sixteenth century. Corn (maize) fields stretch out to the south of the hamlet, mingled with orchards and the occasional wheat field. The vineyards creep up the lower reaches of Monte San Giorgio behind it. Today, Meride boasts a refurbished paleontological museum, designed by star architect Mario Botta; the new museum opened in 2012 with Triassic fossils from Monte San Giorgio on display. In 1967, four years after his death, Peyer was named honorary citizen of Meride, and the street on which the museum is located was named after him, the Via Bernardo Peyer (fig. 1.4). Even today, Meride is not easy to reach from Zurich. An intercity train takes passengers to Lugano, a regional train continues on to Mendrisio, where they have to board the PostBus—the auto da posta—that goes to Meride. Since 1955, fieldwork at Monte San Giorgio has been organized out of Meride. The dig in 1928 at Acqua del Ghiffo targeted limestone deposits, the so-called Cava Superiore layers of the lower Meridekalke (Meride Limestone) of Ladinian age, approximately 238 million years old. These were not the deposits, however, that originally attracted Peyer’s attention or the interest of other paleontologists. Munich paleontology professor and later friend Ferdinand Broili first pointed Peyer in that direction. The slightly older layers of a different nature, approximately 241 to 245 million years old, had first been recognized for their potential to yield a rich variety of fossils: these were the bituminous black shales and dolomites of the so-called Grenzbitumenzone that straddles the Anisian–Ladinian boundary of the Middle Triassic.

Of Oil and Fossils

Since the mid-eighteenth century, the government of Lombardy, based in Milan, had been concerned about maintaining a sufficient energy supply for the city (the present account of the industrial exploitation of the mid-Triassic bituminous layers of Lombardy and Switzerland follows the account by Furrer, 2003:31–34). One source of combustible fuel that could potentially be exploited was the Middle Triassic bituminous layers of rock rich in carbon and oil situated above Besano, a village located just southwest of Porto Ceresio in northwestern Lombardy, near the Italian-Swiss border. Today, these layers are called the Besano Formation. Equivalent outcrops of the same layers on the slopes of Monte San Giorgio were discovered in 1856. These bituminous black shales and dolomites on the Swiss side are called the Grenzbitumenzone. The term Grenzbitumenzone, which translates into “bituminous boundary zone,” was introduced by Albert Frauenfelder (1916:264), as he believed it to form the upper boundary of the Paraceratites trinodosus biozone of Anisian age (268). P. Brack and H. Rieber draw the Anisian-Ladnian boundary at the base of the Eoprotrachyceras curionii biozone, which places the Anisian-Ladinian boundary in the upper part of the Grenzbitumenzone (Brack and Rieber, 1993; see also Brack et al., 2005; see below for further discussion). In the more recent literature, the term Besano Formation has also been applied to the Monte San Giorgio localities because the sediments at both localities were deposited in the same marine basin (Furrer, 2003:37). In this book, I use the terms Besano Formation for the Besano locality and Grenzbitumenzone for the Monte San Giorgio localities; this choice is not for geological reasons but to keep the geography of these fossiliferous deposits from becoming confusing.

The discovery of these bituminous shales marked the beginning of a mining history that involved both Lombardian and Swiss interests. It soon became clear, however, that the carbon content of these bituminous rocks was insufficient for them to serve as an efficient source of energy. What instead became the target of industrial exploitation was their oil content. An oily substance called Saurol (sometimes also referred to as Ichthyol) could be extracted from these black shales through pyrolysis; this became the raw material from which the pharmaceutical industry in Milan and Basel produced anti-inflammatory ointments. The company that headed these efforts, beginning in 1908, was the Società Anonima Miniere Scisti Bituminosi di Meride e Besano, founded in 1906 (Rieber and Lanz, 1999; Felber and Tintori, 2000). The name of the primary substance, Saurol, indicates the occurrence of fossils of saurians in the bituminous shales that this company exploited. The first saurian to be described from the surroundings of Besano was a pachypleurosaur, called Pachypleura Edwardsii by Emilio Cornalia (1824–1882), conservator and later director of the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano, in a publication dating to 1854 (Cornalia, 1854; the valid name of the species today is ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Dragon Mountain

- 2. Fishes

- 3. A Sketch of Reptile Evolution

- 4. Ichthyosaurs

- 5. Helveticosaurus, Eusaurosphargis, and the Placodonts

- 6. Pachypleurosaurs

- 7. Lariosaurs and Nothosaurs

- 8. Thalattosaurs

- 9. Protorosaurs

- 10. A Dinosaur Lookalike from Monte San Giorgio

- 11. The Tethys Sea: Connections from East to West

- Epilogue—In the Shadow of the Chinese Dragon

- Literature Cited

- Index

- About the Author