- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

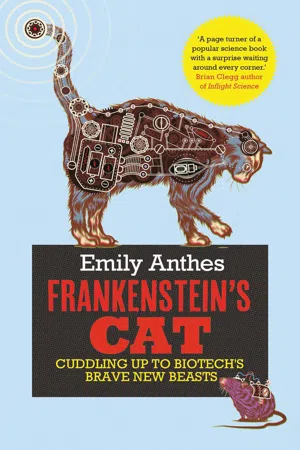

Dolly the Sheep was just the start. Meet the high-tech menagerie of the near future, as scientists reinvent the animal kingdom

From the petri dish to the pet shop, meet the high-tech menagerie of the near future, as humans reinvent the animal kingdom

Fluorescent fish that glow near pollution. Dolphins with prosthetic fins. Robot-armoured beetles that military handlers can send on spy missions. Beloved pet pigs resurrected from DNA. Scientists have already begun to create these high-tech hybrids to serve human whims and needs. What if a cow could be engineered to no longer feel pain – should we design a herd that would assuage our guilt over eating meat?

Acclaimed science writer Emily Anthes travels round the globe to meet the fauna of the future, from the Scottish birthplace of Dolly the sheep and other clones to a ‘pharm’ for cancer-fighting chickens. Frankenstein’s Cat is an eye-opening exploration of weird science – and how we are playing god in the animal world.

From the petri dish to the pet shop, meet the high-tech menagerie of the near future, as humans reinvent the animal kingdom

Fluorescent fish that glow near pollution. Dolphins with prosthetic fins. Robot-armoured beetles that military handlers can send on spy missions. Beloved pet pigs resurrected from DNA. Scientists have already begun to create these high-tech hybrids to serve human whims and needs. What if a cow could be engineered to no longer feel pain – should we design a herd that would assuage our guilt over eating meat?

Acclaimed science writer Emily Anthes travels round the globe to meet the fauna of the future, from the Scottish birthplace of Dolly the sheep and other clones to a ‘pharm’ for cancer-fighting chickens. Frankenstein’s Cat is an eye-opening exploration of weird science – and how we are playing god in the animal world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Go Fish

But one of these animals is not like the others. The discerning pet owner in search of something new and different merely has to head to the aquatic display and keep walking past the speckled koi and fantail bettas, the crowds of goldfish and minnows. And there they are, cruising around a small tank hidden beneath the stairs: inch-long candy-coloured fish in shades of cherry, lime and tangerine. Technically, they are zebrafish (Danio rerio), which are native to South Asian lakes and rivers and usually covered with black and white stripes. But these swimmers are adulterated with a smidgen of something extra. The Starfire Red fish contain a dash of DNA from the sea anemone; the Electric Green, Sunburst Orange, Cosmic Blue and Galactic Purple strains all have a nip of sea coral. These borrowed genes turn the zebrafish fluorescent, so under black or blue lights they glow. These are GloFish, some of the world’s first genetically engineered pets.

Though we’ve meddled with many species through selective breeding, these fish mark the beginning of a new era, one in which we have the power to directly manipulate the biological codes of our animal friends. Our new molecular techniques change the game. They allow us to modify species quickly, rather than over the course of generations; doctor a single gene instead of worrying about the whole animal; and create beings that would never exist in nature, mixing and matching DNA from multiple species into one great living mash-up. We have long desired creature companions tailored to our exact specifications. Science is finally making that precision possible.

Though our ancestors knew enough about heredity to breed better working animals, our ability to tinker with genes directly is relatively new. After all, it wasn’t until 1944 that scientists identified DNA as the molecule of biological inheritance, and 1953 that Watson and Crick deduced DNA’s double helical structure. Further experiments through the ’50s and ’60s revealed how genes work inside a cell. For all its seeming mystery, DNA has a straightforward job: It tells the body to make proteins. A strand of DNA is composed of individual units called nucleotides, strung together like pearls on a necklace. There are four distinct types of nucleotides, each containing a different chemical base. Technically, the bases are called adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine, but they usually go by their initials: A, T, C and G. What we call a ‘gene’ is merely a long sequence of these As, Ts, Cs and Gs. The order in which these letters appear tells the body which proteins to make – and where and when to make them. Change some of the letters and you can alter protein manufacturing and the ultimate characteristics of an organism.

Once we cracked the genetic code, it wasn’t long before we figured out how to manipulate it. In the 1970s, scientists set out to determine whether it was possible to transfer genes from one species into another. They isolated small stretches of DNA from Staphylococcus – the bacteria that cause staph infections – and the African clawed frog. Then they inserted these bits of biological code into E. coli. The staph and frog genes were fully functional in their new cellular homes, making E. coli the world’s first genetically engineered organism. Mice were up next, and in the early 1980s, two labs reported that they’d created rodents carrying genes from viruses and rabbits. Animals such as these mice, which contain a foreign piece of DNA in their genomes, are known as transgenic, and the added genetic sequence is called a transgene.

Encouraged and inspired by these successes, scientists started moving DNA all around the animal kingdom, swapping genes among all sorts of swimming, slithering and scurrying creatures. Researchers embarking on these experiments had multiple goals in mind. For starters, they simply wanted to see what was possible. How far could they push these genetic exchanges? What could they do with these bits and pieces of DNA?

There was also immense potential for basic research; taking a gene from one animal and putting it into another could help researchers learn more about how it worked and the role it played in development or disease. Finally, there were promising commercial applications, an opportunity to engineer animals whose bodies produced highly desired proteins or creatures with economically valuable traits. (In one early project, for instance, researchers set out to make a leaner, faster-growing pig.)

Along the way, geneticists developed some neat tricks, including figuring out how to engineer animals that glowed. They knew that some species, such as the crystal jellyfish, had evolved this talent on their own. One moment, the jellyfish is an unremarkable transparent blob; the next it’s a neon-green orb floating in a dark sea. The secret to this light show is a compound called green fluorescent protein (GFP), naturally produced by the jellyfish, which takes in blue light and reemits it in a kiwi-coloured hue. Hit the jelly with a beam of blue light, and a ring of green dots will suddenly appear around its bell-shaped body, not unlike a string of Christmas lights wrapped around a tree.

When scientists discovered GFP, they began to wonder what would happen if they took this jellyfish gene and popped it into another animal. Researchers isolated and copied the jellyfish’s GFP gene in the lab in the 1990s, and then the real fun began. When they transferred the gene into roundworms, rats and rabbits, these animals also started producing the protein, and if you blasted them with blue light, they also gave off a green glow. For that reason alone, GFP became a valuable tool for geneticists. Researchers testing a new method of genetic modification can practice with GFP, splicing the gene into an organism’s genome. If the animal lights up, it’s obvious that the procedure worked. GFP can also be coupled with another gene, allowing scientists to determine whether the gene in question is active. (A green glow means the paired gene is on.)

Scientists discovered other potential uses, too. Zhiyuan Gong, a biologist at the National University of Singapore, wanted to use GFP to turn fish into living pollution detectors, swimming canaries in underwater coal mines. He hoped to create transgenic fish that would blink on and off in the presence of toxins, turning bright green when they were swimming in contaminated water. The first step was simply to make fish that glowed. His team accomplished that feat in 1999 with the help of a common genetic procedure called microinjection. Using a tiny needle, he squirted the GFP gene directly into some zebrafish embryos. In some of the embryos, this foreign bit of biological code managed to sneak into the genome, and the fish gave off that telltale green light. In subsequent research, the biologists also made strains in red – thanks to a fluorescent protein from a relative of the sea anemone – and yellow, and experimented with adding these proteins in combination. One of their published papers showcases a neon rainbow of fish that would do Crayola proud.1

To Richard Crockett, the co-founder of the company that sells GloFish, such creatures have more than mere scientific value – they have an obvious aesthetic beauty. Crockett vividly remembers learning about GFP in a biology class. He was captivated by an image of brain cells glowing green and red, thanks to the addition of the genes for GFP and a red fluorescent protein. Crockett was a premed student, but he was also an entrepreneur. In 1998, at the age of twenty-one, he and a childhood friend, Alan Blake, launched an online education company. By 2000, the company had become a casualty of the dot-com crash. As the two young men cast about for new business ideas, Crockett thought back to the luminescent brain cells and put a proposal to Blake: What if they brought the beauty of fluorescence genes to the public by selling glowing, genetically modified fish?

At first, Blake, who had no background in science, thought his friend was joking. But when he discovered that Gong and other scientists were already fiddling with fish, he realized that the idea wasn’t far-fetched at all. Blake and Crockett wouldn’t even need to invent a new organism – they’d just need to take the shimmering schools of transgenic fish out of the lab and into our home tanks.

The pair founded Yorktown Technologies to do just that, and Blake took the lead during the firm’s early years, setting up shop in Austin, Texas. He licensed the rights to produce the fish from Gong’s lab and hired two commercial fish farms to breed the pets. (Since the animals pass their fluorescence genes on to their offspring, all Blake needed to create an entire line of neon pets was a few starter adults.) He and his partner dubbed them GloFish, though the animals aren’t technically glow-in-the-dark – at least, not in the same way that a set of solar system stickers in a child’s bedroom might be. Those stickers, and most other glow-in-the-dark toys, work through a scientific property known as phosphorescence. They absorb and store light, reemitting it gradually over time, as a soft glow that’s visible when you turn out all the lights. GloFish, on the other hand, are fluorescent, which means that they absorb light from the environment and beam it back out into the world immediately. The fish appear to glow in a dark room if they’re under a blue or black light, but they can’t store light for later – turn the artificial light off, and the fish stop shining.

Blake was optimistic about their prospects. As he explains, ‘The ornamental fish industry is about new and different and exciting varieties of fish.’ And if new, different, and exciting is what you’re after, what more could you ask for than an animal engineered to glow electric red, orange, green, blue or purple thanks to a dab of foreign DNA? Pets are products, after all, subject to the same market place forces as toys or clothes. Whether it’s a puppy or a pair of heels, we’re constantly searching for the next big thing. Consider the recent enthusiasm for ‘teacup pigs’ – tiny swine cute enough to make you swear off pork chops forever – and adopted by the likes of Jordan.

Harold Herzog, a psychologist at Western Carolina University who specializes in human-animal interactions, has studied the way our taste in animals changes over time. When Herzog consulted the registry of the American Kennel Club, he found that dog breed choices fade in and out of fashion the same way that baby names do. One minute, everyone is buying Irish setters, naming their daughters Lisa, and listening to ‘Tiger Feet’ – welcome to 1974! – and then it’s on to the next great trend. Herzog discovered that between 1946 and 2003, eight breeds – Afghan hounds, chows, Dalmatians, Dobermanns, Great Danes, Old English sheepdogs, rottweilers and Irish setters – went through particularly pronounced boom and bust cycles in the US. Registrations for these canines would skyrocket, and then, as soon as they reached a certain threshold of popularity, Americans would begin searching for their next fur-covered fad.

Herzog identified a modern manifestation of our long-standing interest in new and unusual animals. In antiquity, explorers hunted for far-flung exotic species, which royal house holds often imported and displayed. Even the humble goldfish began as a luxury for the privileged classes. Native to Central and East Asia, the wild fish are usually covered in silvery grey scales. But ancient Chinese mariners had noticed the occasional yellow or orange variant wriggling in the water. Rich and powerful Chinese families collected these mutants in private ponds, and by the thirteenth century, fish keepers were breeding these dazzlers together. Goldfish domestication was born, and the once-peculiar golden fish gradually spread to the homes of less-fortunate Chinese families – and house holds elsewhere in Asia, Europe and beyond.

As goldfish grew in popularity, breeders stepped up their game, creating ever more unusual varieties. Using artificial selection, they created goldfish with freakish and fantastical features, and the world’s aquariums now contain the fantail, the veiltail, the butterfly tail, the lionhead, the goosehead, the golden helmet, the golden saddle, the bubble eye, the telescope eye, the seven stars, the stork’s pearl, the pearlscale, the black moor, the panda moor, the celestial, and the comet goldfish, among others. This explosion of types was driven by the desire for the exotic and exquisite – urges that we can now satisfy with genetically modified pets.

We can also use genetic engineering to create animals that appeal to our aesthetic sensibilities, such as our preference for brightly coloured animals. For instance, a 2007 study revealed that we humans prefer penguin species that have a splash of yellow or red on their bodies to those that are simply black and white. We’ve bred canaries, which are naturally a dull yellow, to exhibit fifty different colour patterns. And before GloFish were even a neon glint in Blake’s eye, some pet shops were selling ‘painted’ fish that had been injected with simple fluorescent dyes. With fluorescence genes, we can make a true rainbow of bright and beautiful pets.2

Engineered pets also fit right into our era of personalization. We can have perfume, granola and Nikes customized to our individual specifications – why not design our own pets? Consider the recent rise of designer dogs, which began with the Labradoodle, a cross between a Labrador retriever and a standard poodle. Though there’s no telling when the first Lab found himself fancying the well-groomed poodle down the street, most accounts trace the origin of the modern Labradoodle to Wally Conron, the breeding director of the Royal Guide Dog Association of Australia. In the 1980s, Conron heard from a blind woman in Hawaii, who wanted a guide dog that wouldn’t aggravate her husband’s allergies. Conron’s solution was to breed a Lab, a traditional seeing-eye dog, with a poodle, which has hypoallergenic hair. Other breeders followed Conron’s lead, arranging their own mixed-breed marriages. The dogs were advertised as providing families with the best of both worlds – the playful eagerness of a Lab with the smarts and hypoallergenic coat of the poodle. The rest, as they say, is history. The streets are now chock-full of newfangled canine concoctions: puggles (a pug-beagle cross), dorgis (dachshund plus corgi) and cockapoos (a cocker spaniel–miniature poodle mix). There’s even a mini Labradoodle for doodle lovers without lots of space.

Tweaking the genomes of our companions allows us to create a pet that fulfills virtually any desire – some practical, some decidedly not. When I set out to get a dog, I thought I had settled on the Cavalier King Charles spaniel: a small, soft dog bred for companionship. Then I discovered a breeder who was crossing Cavaliers with miniature poodles, yielding the so-called Cavapoo. I was sold. I loved the scruffier, shaggier hair of the Cavapoo, and given what I knew about biology, I figured that a hybrid was less likely to inherit one of the diseases that plague perilously inbred canines. A dog that didn’t shed would be an added bonus. Plus, poodles have a reputation for being brainy, and I’m an overachiever; if I was going to get a dog, I wanted to be damn sure he’d be at the top of his puppy class.

The hitch: Even the most careful selective breeding is a rough science. Sure, Labs are friendly and poodles are clever, but just letting them go at it doesn’t guarantee that their puppies will exhibit the best of both breeds. Milo, the Cavapoo I brought home, looks almost entirely like a spaniel, and as for a nonshedding coat, his health and those famous poodle ‘smarts’? Well, my sofa is covered with dog hair, Milo has a knee problem common in purebred Cavaliers, and I’m pretty sure he got the spaniel brain. So much for my plan to outsmart nature.

When I’m ready for my next pet, the landscape could be radically different. Social Technologies, a trend forecasting firm in Washington, DC, issued a report on the commercial prospects for genetically modified pets. ‘Through advances in genetic modification’, the report said, ‘biotechnology labs could join kennels and animal shelters as a source for the perfect pet . . . Initially a luxury, pet personalization would become available to the general public as the technologies involved become more mature’.

Indeed, why bother creating clumsy crosses when we can edit genes directly? An American company called Felix Pets, for example, is attempting to engineer cats that are missing a gene called Fel d 1, which codes for a protein that triggers human allergies.3 And that’s just the beginning. What if you could order up a fish created in your school’s colours or dogs and cats with custom patterns on their coats? Or there’s the ultimate designer pet, proposed by Alan Beck, director of Purdue’s Center for the Human-Animal Bond in Indiana: ‘If we’re going to come up with genetically engineered animals, we might be able to come up with an animal that loves only you’.

Transgenic pets will have to clear some hurdles before they make it to market. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers a new gene that is added to an organism to be a ‘drug’, and regulates altered animals under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Companies seeking approval to sell an engineered animal must demonstrate that the transgene has no ill effects on the animal itself. If the animal will be a source of food, companies must also demonstrate that it is safe for human consumption. In the EU, genetically modified organisms are subject to a variety of different regulations and directives and must receive prior authorization before being placed on the market. The European Commission and all EU member states are involved in this approval process, as is the European Food Safety Authority when the organism is intended for food or animal feed.

On both sides of the Atlantic, regulators also evaluate how a genetically modified organism might affect the environment if it happened to make its way into the wild – either by mistake or by plan. Escape has been a concern since the first genetically engineered bacteria were created in the early 1970s. The scientists of that era worried about what might happen if they inadvertently created a dangerous superbug and it slipped out under the laboratory door. Biologists convened twice – at the Asilomar conferences of 1973 and 1975 – to discuss these risks. In 1975, they drew up a document that encouraged their colleagues to exercise caution and use ‘biological and physical barriers’ to ensure that novel organisms didn’t break free from the lab. The US National Institutes of Health issued guidelines stipulating such safeguards in 1976 and has periodically updated its recommendations over the years; similar procedures are incorporated into the EU directives and UK laws.

Though these containment strategies are routine in many countries, they aren’t foolproof, and ecologists continue to worry about engineered organisms ending up in the wild. Altered animals could ‘pollute’ the gene pool by breeding with their free-range cousins, or snatch food and resources away from native organisms. In theory, laboratory manipulation could make a fish more likely to thrive in the big, wide world, and such Frankenfish could take over natural waterways, to the detriment of other species.

This very possibili...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Go Fish

- 2. Got Milk?

- 3. Double Trouble

- 4. Nine Lives

- 5. Sentient Sensors

- 6. Pin the Tail on the Dolphin

- 7. Robo Revolution

- 8. Beauty in the Beasts

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Frankenstein's Cat by Emily Anthes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Emergency Medicine & Critical Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.