eBook - ePub

Climate Change

A Beginner's Guide

Emily Boyd, Emma L. Tompkins

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Climate Change

A Beginner's Guide

Emily Boyd, Emma L. Tompkins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The heat is on in the race to save the planet Climate change is the greatest single problem we face as a planet. This important introduction skilfully guides us through the complex mix of scientific, political, social, and environmental issues to examine the manifold threats it poses and explore the possible futures for our world. Focusing on the fact that the point of no return, may in fact have already been passed, Boyd and Tompkins highlight the urgent need to start actively adapting to our changing climate if we want to avoid complete catastrophe.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Climate Change an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Climate Change by Emily Boyd, Emma L. Tompkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Meteorology & Climatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Meteorology & Climatology1

The climate is

changing

‘Today, the time for doubt has passed. The IPCC has unequivocally affirmed the warming of our climate system and linked it directly to human activity.’

(Ban Ki-Moon, United Nations Secretary General,

September 2007)

There is no doubt: the world is getting warmer.

This warming is largely caused by greenhouse gas emissions associated with human activity. The more than two and a half thousand scientists who comprise the international Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have concluded that climate change is a truly global phenomenon that requires global action – a challenge that mankind has never before had to confront.

Humans have been adapting to a changing Earth for millennia, but the revolution we will have to face from climate change is unprecedented. Human creativity and ingenuity has improved our lives and enhanced our development prospects through our industries, making greenhouse gases (water vapour, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and hydrofluorocarbons) along the way. Now, we know that these gases are stored in the atmosphere, where they act like a blanket, preventing the sun’s reflected heat from leaving the atmosphere. Not all gases remain in the atmosphere for the same time: nitrous oxide has an effective lifetime of about 100–150 years, carbon dioxide about 100 years and methane twelve years. We will have to live with increasing concentrations of these gases in the atmosphere – and hence increased warming of our planet – for many generations to come.

The Industrial Revolution, which started in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was a turning point for our planet. During this period, national economies shifted from agricultural, driven by manual labour, to industry, driven by new technologies powered first by water and later by steam. Technology gave us more and more ways to use energy to make life easier, faster and richer: steam-powered ships, railways and factories; internal combustion engines; and the generation of electric power. Only now, as we see increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, are we realising the true cost of these fossil-fuel-powered technological innovations.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide – one of the most important greenhouse gases – has increased from 280ppm to 385ppm and methane concentrations from 715 parts per billion (ppb) to 1774ppb. Geological evidence suggests that the Earth’s temperature has been significantly higher, and carbon dioxide concentrations possibly as great as 450ppm, but these conditions occurred before the evolution of humans. We now expect the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to rise above 450ppm before the end of the twenty-first century; we simply do not know what the Earth will be like when that happens.

The increase in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases has been linked to their production by humans. In their Fourth Assessment Report, published in 2007, the IPCC estimated that between 1970 and 2004, greenhouse gas emissions increased by 70%. The largest increase, of 145%, was from the activities of the energy supply industry. Emissions from transport increased by 120% and from general industry by 65%. Other activities which are large emitters of greenhouse gases (see Figure 1) include clearing land, changing land use, agriculture and building.

Figure 1 Global greenhouse gas emissions in 2000 (source: adapted from Emmanuelle Bournay, UNEP/GRID-Arendal)

Projections of the future levels of greenhouse gas emissions have changed little over the past few years. This is not because of a lack of new information, but rather because present and past assessments match well, which suggests that we are very close to identifying the impact of continued increases in greenhouse gas levels. In 2001, when the IPCC produced its third major review of climate science and projections of future impacts, average global surface temperatures were expected to increase by between 1.5°C and 4.5°C by 2100. In 2007, using new data and models, the IPCC reassessed the situation. They now calculate the temperature will rise by between 1.1°C and 6.4°C, with the best estimates lying between 1.8°C and 4°C. It is clear that global warming is not stopping. While this will almost certainly cause significant problems for our planet over the coming decades, we must not forget that it may also bring opportunities: farmers may be able to grow new, higher-value crops, or be more productive with current ones, and new tourist ventures will emerge in new parts of the world.

As we will show, climate change is already causing rising average temperatures, sea level rises, increasing acidity of the oceans and more intense storms and sea surges. Everyone on Earth must consider what we need to do. ‘We’ are the rich and the poor; the people of the developed and those of the developing world. Politicians and scientists must keep the question of how to address climate change at the front of their minds, yet without creating panic. Climate change is a problem of risk: societies are vulnerable to the problems it causes, yet may also prove resilient and adaptable.

Climate change – a real and present danger?

People ask us: is climate change a natural phenomenon that has happened often on Earth? What has climate change got to do with freaky weather and what is the weather going to do next? How is climate change different from weather variation? Why is the science of climate change different now from how it was in the past? What are the risks of sudden climate change plunging us into a new Ice Age? Could there really be a 6°C increase in the Earth’s temperature?

What are the barriers to our understanding the truth about climate change and why is there so much debate? Most people rely on the news media for information, yet the media give us many conflicting messages about climate change. The opinions delivered sometimes depend on the political interests of the proprietors, journalists and editors. Few journalists have any training in atmospheric chemistry and their lack of understanding, and desire to find attention-grabbing stories, combine to produce articles that too often hide the reality of the situation, either denying it is a problem or magnifying it into too large a problem.

Since the 1800s, scientists have known that there is a direct relationship between the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the average Earth temperature. The more carbon dioxide that is pumped into the atmosphere, the more the Earth’s temperature goes up. This is simple physics, and is supported by the evidence of hundreds of climate models. It is indisputable. Yet, despite this long awareness of the evidence, until the mid-1980s the problems and challenges of climate change were largely unknown to people outside the research community. Contrast this with the early twenty-first century; now, even businesses compete to show their concern through public statements and research. In 2003, the huge insurance company Swiss Re expressed its concerns about the costs of climate change; in 2007, the bank HSBC funded a survey of 9,000 people on nine continents to assess their concerns about climate change; in the same year the financial institutions UBS and Citigroup published documents describing how climate change is shifting their exposure to risk.

These are just some of the many corporate initiatives trying to identify the impacts of climate change on business. But government and business concerns about climate change are not necessarily shared by the public. Popular fiction has even been written about the ‘hoax’ of climate change (such as Michael Crichton’s State of Fear, published in 2004). Such ‘climate change-denying’ novels are written to sell, with themes of conspiracy and suggestions of hidden motives. However, no reputable scientists deny that our climate is changing. Climate change-deniers have been proved wrong and now look more like those who clung on to a belief that the Earth was flat long after it was proved to be spherical.

A handful of scientists remain ‘climate change-sceptics’ but they are a different breed to ‘climate change-deniers’. They agree that the climate is changing but remain either mistrustful of the quality of climate models – suggesting that future predictions are too extreme – or argue that there might be other causes of change (such as sunspots) for which current climate models do not adequately account. Climate change-sceptics have an important role to play in the quest to understand climate change; their scepticism pushes other scientists into improving the quality of their climate models and identifying the ratio of human activity and other factors in contributing to climate change.

How did we get here and what do we know about the future?

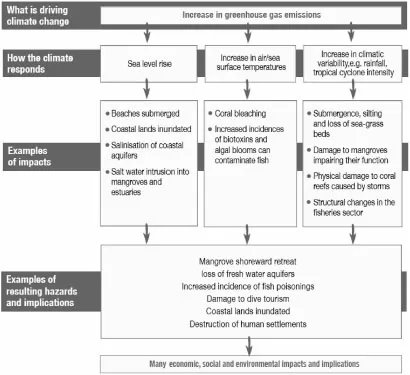

Climate change exerts its effects on our lives in complex ways. Everything is connected. Producing greenhouse gases affects the global climate, which affects the weather and the way the oceans function (see Figure 2). The changing weather – storms, floods and other extremes – and ocean behaviour affect our capacity to grow food, find clean water or travel. Our response to these changes affects our emissions of greenhouse gases.

In 2007, the United Nations released three important reports, written by the IPCC, which made it clear that climate change is now ‘unequivocal’. The IPCC was formed in 1988, under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organisation, to provide the best possible assessments of climate change. Scientists from the IPCC have measured, analysed and modelled many aspects of climate, including temperature, precipitation, storminess, extreme weather and weather hazards. Four sets of reports have now been produced (in 1990, 1995, 2001 and 2007). Each includes reports on the science of climate change, the impacts of climate change and proposed solutions. Each report is reviewed and revised by many scientists, many times, over its five-year preparation period. The reports’ conclusions summarise the findings of more than two thousand scientists, whose contributions to these assessments are voluntary, and so are not the view of any single scientist. In 2007, the scientists involved in the IPCC were collectively awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (jointly with former US Vice-President Al Gore), for their contribution to our understanding of climate change.

Figure 2 The inter-linkages between the human emissions of greenhouse gases and the changing coast (Source: Tompkins et al., 2005)

According to the scientists who worked on the 2007 IPCC report, the Earth has warmed by about 0.75°C since 1860. They also point out that, of the thirteen years between 1995 and 2007, eleven are among the warmest recorded since 1850. Their evidence comes from dozens of high-quality temperature records compiled from data collected from land and sea. The report also states that the current concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and the rates of change, are unprecedentedly high. Scientists are able to find past levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere by analysing ‘ice cores’, long tubes of ice drilled from the ice of the Arctic and Antarctic. Using these ice cores, and the sediment extracted from them, we are able to assess concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere over the past million years. It is undeniable that concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide have increased significantly since the mid-nineteenth century, broadly since the Industrial Revolution in the developed world.

Information gathered from ice cores and sediments, in conjunction with techniques such as radiometric dating, ocean carbon levels, and other palaeo-climatic data, enables scientists to map the changes in global temperature over time and tell us how humans are affecting the Earth’s climate. We know that the climate has been remarkably stable since the beginnings of human civilisation, about 6,000 years ago. And we also know that never before has the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increased as quickly as it has done since the 1800s. No modern humans have ever witnessed such rapid change in the climate system as we are seeing now. This makes it extremely challenging to understand what is happening, particularly since we cannot see the changes at first-hand. It is also difficult to think conceptually or envisage how we can adapt and change quickly enough.

Scientists now have higher confidence not only in the projected patterns of warming but also in other features, including changes in wind patterns, precipitation, sea ice and extreme weather. Globally, water is a crucial issue, although the effects vary geographically. Scientists have observed an increasing frequency of heavy bursts of rain over most areas of the world. In 2005, in Mumbai, India, 94 centimetres of rain fell in one day; unprecedented in recorded history. Between 1900 and 2005, precipitation increased significantly in eastern parts of North and South America, northern Europe and northern and central Asia but declined in the Sahel, the Mediterranean, southern Africa and parts of southern Asia. Globally, the area affected by drought has increased since the 1970s. In Africa, by 2020, between 75 and 250 million people may suffer water shortages. In some areas, agricultural yields may be reduced by 50% if farmers do not shift to drought-resistant crops. In Asia, scientists estimate that by the 2050s, freshwater will be much less available and coastal areas will be at greater risk from sea inundation. Water shortages are also anticipated on small islands. Between 1961 and 1993, sea levels rose more quickly than ever before. In 1961, sea-level rises were about 1.8mm a year; by 1993, annual average sea level rise was 3.1mm. These rises are mostly due to thermal expansion of the oceans (as liquids become warmer, they expand). As the atmosphere has become warmer, this has warmed the surface layers of the oceans and they have increased in volume. The melting of glaciers, ice caps and polar ice sheets also affects sea levels. Scientists estimate that by the end of the twenty-first century, sea levels could rise by between 18 and 59cm. The partial loss of ice sheets on polar land could bring an additional 20 to 60cm rise. Such rises will bring about major changes to coastlines and cause inundation of low-lying areas. River deltas and low-lying islands, presently inhabited by millions of people, will be very badly affected. Small island states, such as the Marshall Islands, are expected to experience increased inundation, storm surge erosion and other coastal hazards, which will threaten their essential infrastructure. Warmer oceans could also change the ocean currents (such as the Meridional Overturning Circulation) that carry warm water into far northern latitudes and return cold water southward. Large and persistent changes in these currents will affect marine ecosystem productivity, fisheries, ocean carbon dioxide uptake and land vegetation.

CLIMATE OR WEATHER?

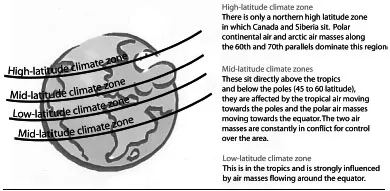

We all know there is a difference between climate and weather. Weather is the day-to-day fluctuation that determines whether we carry an umbrella or wear a sunhat on our way to work. Irregularities, like an unusually hot day in winter or snow in summer, do not imply dramatic climate change – they are simply anomalies. We experience different kinds of daily weather in the different climate zones around the world. Temperate climate zones have four seasons (spring, summer, autumn and winter), each with their expected heat, rain and storms; tropical climate zones have wet and dry seasons, with very different average daily temperatures. Climate change refers to significant shifts in weather over time: a wet season becoming consistently wetter, a dry season lengthening or the monsoon season becoming less predictable.

Figure 3 Climate zones around the Earth

The Köppen Climate Classification System is a standard system used to describe the Earth’s climates. In 1900, Wladimir Köppen classified the world’s climatic regions, broadly in line with the global classification of vegetation and soils. In this system, which is based on temperature and precipitation, there are five main climate types: Moist Tropical Climates (high year-round temperatures and precipitation); Dry Climates (very little precipitation and significant daily variation in temperatures); Humid Middle Latitude Climates (warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters); Continental Climates (low precipitation and significant seasonal variation in temperature); and Cold Climates (permanent ice and tundra and fewer months of the year above freezing than below). These five climate types can be found in the three planetary climate zones, delineated by the air masses that affect them.

The effects of climate change experienced around the world will, to a large extent, be determined by the choices we are making now. We can make the problem far worse by pursuing lifestyles that require high levels of fossil fuels or we can lessen the impacts by adopting low-carbon lifestyles, saving energy and reducing our emissions. Our future impacts can also be reduced if we start planning today. We do not have to experience the terrible losses of wild storms or horrific floods. Yet the complex and subtle dance of leader and follower between the private sector and the state is, in many ways, slowing down these vital preparations. The private sector is waiting for leadership and guidance from the state, yet in most countries the state is reluctant to impose unpopular controls.

What is at stake?

Climate change is frequently framed as a problem of risk and vulnerability, rather than of impacts and responses. Such use of language contributes to the confusion about what is really happening. Understanding risk and vulnerability will significantly enhance our ability to prepare for climate change. They can perhaps be most easily understood by considering what they mean in specific regions and countries.

China has a large number of very poor people living in rural areas with limited natural resources, who are therefore sensitive to drought. Some parts of China are highly prone to drought simply because of their geography and topography; they just never receive much rain. The picture is similar throughout Southern Asia, making it particularly at risk to climate change. Vulnerability extends beyond geography. The after-effects of colonialism, such as democratisation, land-partitioning and the imposition of unnatural boundaries, have left densely-populated marginal countries (for example, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India) vulnerable to extreme climate-related stress. In all these countries, the melting of mountain glaciers is radically altering river flows and sea-level rises are drowning river deltas.

Neither is the developed world invulnerable to climate change, yet houses are stil...