- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

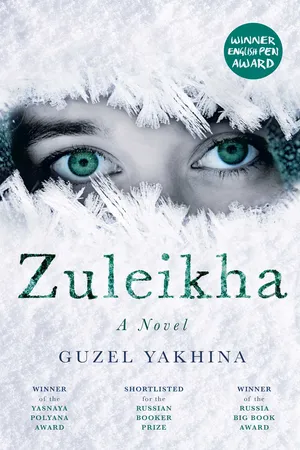

WINNER OF THE BIG BOOK AWARD, THE LEO TOLSTOY YASNAYA POLYANA AWARD AND THE BEST PROSE WORK OF THE YEAR AWARD

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2020 READ RUSSIA PRIZE

RUNNER-UP FOR THE EBRD LITERATURE PRIZE, 2020

Zuleikha is the model of a dutiful wife. Biddible and meek, she has resigned herself to brutal treatment at the hands of her cruel husband and the carping of her despotic mother-in-law. While Russia reels in the aftermath of its recent revolution, life in her small Tatar village is relatively untouched. Or so it seems to Zuleikha, until the day her husband is executed by communist soldiers.

Zuleikha is exiled to Siberia and forced to leave behind everything she knows. Yet in that harsh, desolate wilderness, she begins to build a new life for herself and discovers an inner strength she never knew she had. This is a supremely ambitious epic about one woman's determination, not only to survive, but to flourish in the face of the greatest adversity.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2020 READ RUSSIA PRIZE

RUNNER-UP FOR THE EBRD LITERATURE PRIZE, 2020

Zuleikha is the model of a dutiful wife. Biddible and meek, she has resigned herself to brutal treatment at the hands of her cruel husband and the carping of her despotic mother-in-law. While Russia reels in the aftermath of its recent revolution, life in her small Tatar village is relatively untouched. Or so it seems to Zuleikha, until the day her husband is executed by communist soldiers.

Zuleikha is exiled to Siberia and forced to leave behind everything she knows. Yet in that harsh, desolate wilderness, she begins to build a new life for herself and discovers an inner strength she never knew she had. This is a supremely ambitious epic about one woman's determination, not only to survive, but to flourish in the face of the greatest adversity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

THE PITIFUL HEN

ONE DAY

Zuleikha opens her eyes. It’s as dark as a cellar. Geese sigh sleepily behind a thin curtain. A month-old foal smacks his lips, searching for his mother’s udder. A January blizzard moans, muffled, outside the window by the head of the bed. Thanks to Murtaza, though, no draft comes through the cracks. He sealed up the windows before the cold weather set in. Murtaza is a good master of the house. And a good husband. His snoring booms and rumbles in the men’s quarters. Sleep soundly: the deepest sleep is just before dawn.

It’s time. All-powerful Allah, may what has been envisioned be fulfilled. May nobody awaken.

Zuleikha noiselessly lowers one bare foot then the other to the floor, leans against the stove, and stands. The stove went out during the night, its warmth is gone, and the cold floor burns the soles of her feet. She can’t put on shoes. She wouldn’t be able to make her way silently in her little felt boots; some floorboard or other would surely creak. Fine, Zuleikha will manage. Holding the rough side of the stove with her hand, she feels her way out of the women’s quarters. It’s narrow and cramped in here but she remembers every corner, every little shelf: for half her life she’s been slipping back and forth like a pendulum, carrying full, hot bowls from the big kettle to the men’s quarters, then empty, cold bowls back from the men’s quarters.

How many years has she been married? Fifteen of her thirty? Is that half? It’s probably even more than that. She’ll have to ask Murtaza when he’s in a good mood – let him count it.

Don’t stumble on the rug. Don’t hit a bare foot on the trunk with the metal trim, to the right, by the wall. Step over the squeaky board where the stove curves. Scurry soundlessly behind the printed cotton curtain separating the women’s quarters of the log house from the men’s … It’s not far to the door now.

Murtaza’s snores are closer. Sleep, sleep, for Allah’s sake. A wife shouldn’t hide anything from her husband, but sometimes she must, there’s no helping it.

The main thing now is not to wake the animals. They usually sleep in the winter shed but Murtaza orders the birds and young animals to be brought inside during cold snaps. The geese aren’t stirring but the foal taps his hoof and shakes his head; he’s awake, the imp. He’s sharp: he’ll be a good horse. Zuleikha stretches her hand through the curtain and touches his velvety muzzle: Calm down, you know me. His nostrils snuffle gratefully into her palm, recognizing her. Zuleikha wipes her damp fingers on her night-shirt and lightly pushes the door with her shoulder. Thick and padded with felt for the winter, the door gives way heavily, and a frosty, biting cloud flies in through the crack. She takes a big step over the high threshold so as not to jinx anything – treading on it now and disturbing the evil spirits would be all she needs – and then she’s in the entrance hall. She closes the door and leans her back against it.

Glory be to Allah, part of the journey has been made.

It’s as cold in the hallway as outside, nipping at Zuleikha’s skin so her nightshirt doesn’t warm her. Streams of icy air beat at the soles of her feet through cracks in the floor. This isn’t what troubles her, though.

What troubles her is behind the door opposite.

Ubyrly Karchyk – the Vampire Hag. That’s what Zuleikha calls her, to herself. She thanks the Almighty that they don’t live in the same house as her mother-in-law. Murtaza’s home is spacious, two houses connected by a common entrance hall. On the day forty-five-year-old Murtaza brought fifteen-year-old Zuleikha into the house, the Vampire Hag – her face a picture of martyred grief – dragged her own numerous trunks, bundles, and dishes into the guest house, and occupied the whole place. “Don’t touch!” she shouted menacingly at her son when he tried to help her move. Then she didn’t speak to him for two months. That same year, she quickly and hopelessly began to go blind, and then, shortly thereafter, to lose her hearing. A couple of years later, she was as blind and deaf as a rock. She now talks constantly and can’t be stopped.

Nobody knows how old she really is. She herself insists she’s a hundred. Murtaza sat down to count recently, and he sat for a long time before announcing: “Mama’s right, she truly is around a hundred.” He was a late child and is already almost an old man himself.

The Vampire Hag usually wakes up before everyone else and carries her carefully guarded treasure to the entrance hall: an elegant milky-white porcelain chamber pot with a fanciful lid and delicate blue cornflowers on the side. Murtaza brought it back from Kazan as a gift at one time or other. Zuleikha is supposed to jump at her mother-in-law’s call, then empty and carefully wash out the precious vessel first thing, before she stokes the fire in the stove, makes the dough, and takes the cow out to the herd. Woe unto Zuleikha if she sleeps through the morning wake-up call. It’s happened twice in fifteen years and she doesn’t allow herself to recall the consequences.

For now, it’s quiet behind the door. Go on, Zuleikha, you pitiful hen, hurry up. It was the Vampire Hag who first called her zhebegyan tavyk – pitiful hen. Zuleikha started calling herself this after a while, too, without even noticing.

She steals into the depths of the hallway, toward the attic staircase. She gropes at the smooth banister. The steps are steep; the frozen boards occasionally groan just enough to be heard. Scents of chilly wood, frozen dust, dried herbs, and a barely noticeable aroma of salted goose waft down from above. Zuleikha goes up: the blizzard’s din is closer, and the wind pounds at the roof and howls at the corners.

She decides to go on all fours across the attic because were she to walk, the boards would creak right over the sleeping Murtaza’s head. If she crawls, though, she can scurry through. She weighs so little that Murtaza can lift her with one hand, as if she were a young ram. She pulls her nightshirt to her chest so it won’t get all dusty, twists it, takes the end in her teeth, and gropes her way between boxes, crates, and wooden tools, cautiously crawling over the crossbeams. Her forehead knocks into the wall. Finally.

She raises herself up a little and peers out of the small attic window. She can hardly make out the houses of her native Yulbash, all drifted in snow, through the dark, gray gloom just before morning. Murtaza once counted, reaching a total of more than a hundred and twenty homesteads. A large village, that’s for sure. A village road smoothly curves and flows off toward the horizon, like a river. Windows are already lighting in some houses. Quickly, Zuleikha.

She stands and reaches up. Something heavy and smooth, with large bumps, settles into her hands: salted goose. Her stomach jolts, growling in demand. No, she can’t take the goose. She lets go of the bird and searches further. Here! Hanging to the left of the attic window are large, heavy sheets of paste that have hardened in the cold but give off a slight fruity smell. Apple pastila. The confection was painstakingly cooked in the oven, neatly rolled out on wide boards, and dried with care on the roof, soaking up hot August sun and cool September winds. You can bite off a tiny bit and dissolve it for a long time, rolling the rough, sour little piece along the roof of your mouth, or you can cram a lot in, chewing and chewing the resilient wad and spitting occasional seeds into your palm. Your mouth waters right away.

Zuleikha tears a couple of sheets of pastila from the string, rolls them up tightly, and sticks them under her arm. She runs a hand over the rest. There’s still a lot, quite a lot, left. Murtaza shouldn’t figure anything out.

And now to go back.

She kneels and crawls toward the stairs. The rolled-up pastila prevents her from moving quickly. She truly is a pitiful hen now: she hadn’t even thought to bring any kind of bag with her. Zuleikha goes down the stairs slowly, walking on the edges of her curled-up feet because the soles are so numb she can’t feel them. When she reaches the last step, the door on the Vampire Hag’s side swings open noisily and a shadowy silhouette appears in the black opening. A heavy walking stick knocks at the floor.

“Anybody there?” the Vampire Hag’s deep, masculine voice asks the darkness.

Zuleikha goes still. Her heart pounds and her stomach shrinks into an icy ball. She wasn’t fast enough. The pastila is thawing, softening under her arm.

The Vampire Hag takes a step forward. In fifteen years of blindness, she has learned the house by heart, so she moves around here freely and confidently.

Zuleikha flies up a couple of stairs, her elbow squeezing the softened pastila to her body more firmly.

The old woman turns her chin in one direction then another. She doesn’t hear or see a thing but she senses something, the old witch. Yes, a Vampire Hag. Her walking stick knocks loudly, closer and closer. Oh, she’ll wake up Murtaza!

Zuleikha jumps a few steps higher, presses against the banister, and licks her chapped lips.

The white silhouette stops at the foot of the stairs. The old woman’s sniffing is audible as she noisily draws air through her nostrils. Zuleikha brings her palms to her face. Yes, they smell of goose and apples. The Vampire Hag makes a sudden, deft lunge forward and swings, beating at the stairs with her long walking stick, as if she’s hacking them in half with a sword. The end of the stick whistles somewhere very close and smashes into a board, half a toe’s length from the bare sole of Zuleikha’s foot. Feeling faint from fright, Zuleikha flops on the steps like dough. If the old witch strikes once more … The Vampire Hag mumbles something unintelligible and pulls the walking stick toward herself. The chamber pot clinks dully in the dark.

“Zuleikha!” The Vampire Hag’s shout blares toward her son’s quarters.

Mornings usually start like this in their home.

Zuleikha forces herself to swallow. Has she really escaped notice? Carefully placing her feet, Zuleikha creeps down the steps. She bides her time for a couple of moments.

“Zuleikhaaa!”

Now it’s time. Her mother-in-law doesn’t like to say it a third time. Zuleikha bounds over to the Vampire Hag, “Right here, right here, Mama!” and she takes from her hands a heavy pot covered with a warm, sticky moistness, just as she does every day.

“You turned up, you pitiful hen,” her mother-in-law grumbles. “All you know how to do is sleep, you lazybones.”

Murtaza has probably already woken up from the noise and may come out to the hallway. Zuleikha presses the rolled-up pastila more tightly under her arm (she can’t lose it outside!), gropes with her feet at someone’s felt boots on the floor, and races out. The storm beats at her chest and takes her in its solid fist, trying to knock her down. Zuleikha’s nightshirt rises like a bell. The front steps have turned into a snowdrift overnight and Zuleikha walks down, feeling carefully for the steps with her feet. She trudges to the outhouse, sinking in almost to her knees. She fights the wind to open the door. She hurls the contents of the chamber pot into the icy hole. When she comes back inside, the Vampire Hag has already gone to her part of the house.

Murtaza drowsily greets Zuleikha at the threshold with a kerosene lamp in his hand. His bushy eyebrows are knitted toward the bridge of his nose, and his cheeks, still creased from sleep, have wrinkles so deep they might have been carved with a knife.

“You lost your mind, woman? Out in a blizzard, undressed?”

“I just took Mama’s pot out and back.”

“You want to lie around sick half the winter again? So the whole household’s on me?”

“What do you mean, Murtaza? I didn’t get cold at all. Look!” Zuleikha holds out her bright-red palms, firmly pressing her elbows to her waist; the pastila bulges under her arm. Is it visible under her shirt? The fabric got wet in the snow and is clinging to her.

But Murtaza’s angry and isn’t even looking at her. He spits off to the side, stroking his shaved skull and combing his splayed fingers through his scruffy beard.

“Get us some food. And be ready to leave after you clear the yard. We’re going for firewood.”

Zuleikha gives a low nod and scurries behind the curtain.

She did it! She really did it – yes, she, Zuleikha, yes, she, the pitiful hen! And there they are, the spoils: two crumpled, twisted, clumped-up pieces of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Part One: The Pitiful Hen

- Part Two: Where to?

- Part Three: To Live

- Part Four: Return

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina, Lisa C. Hayden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.