![]()

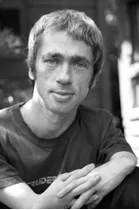

Mat Fraser: Actor/Performer

Photograph taken by JW Evans

The Bill, ITV’s long-running police drama, is listed on the CV of many actors, an accepted part of their career trajectory. For Mat Fraser, it didn’t happen. Born with short arms and flipper-like hands that have no thumbs – the result of his mother taking the drug thalidomide in pregnancy – Fraser was a former rock musician, carving a place for himself as an actor, writer and presenter. Exuberant, ambitious and sexy, he had kicked his way out of the passive, ‘can’t do’, ‘shouldn’t do’ expectations put upon disabled people, flouting many social conventions along the way. When his agent sent him to audition for The Bill in 2000, he was no stranger to mainstream acting and well known in disability arts. ‘I had a long audition,’ he remembers, ‘and the guy loved me, he really loved me. He said, “Mat, you’ve got a very Bill voice. We’ll call you.”’ The call never came. When Fraser’s agent checked, she was told he had not been offered the part because they needed someone who could drive. Yet there, on the front page of his CV, was the information that he had 20 years’ driving experience and a clean licence. It was the same old story. ‘I had been turned down for a disablist reason,’ he says. ‘But we exposed their lie.’

Fraser went on to prove himself in theatre, film, radio and television, culminating in the role of Chris in Every Time You Look At Me, an award-winning, 90-minute drama for BBC Two. The BBC broke new ground by commissioning a full-length film starring two disabled actors – the other was Lisa Hammond (Denny in Grange Hill) – and going beyond the love story to explore their own prejudices: ‘Every time you look at me, you see yourself.’ The love-making was also a first, and so was the manner of it. ‘She’s kissing my most disabled bits and that’s another benchmarky moment, innit?’ says Fraser. ‘Normally the person playing opposite me would go “Ooh, what muscular legs you have, Mat” – i.e. you may be weird up top but you’re still a good lad down there, aren’t ya? And I love the fact that we’re not doing that.’ It was also the first BBC film to be shot on high-definition digital video. Widely praised for the quality of its acting, it won the highest audience appreciation for any BBC drama in 2004. Fraser had arrived – or so he thought.

Given that acting was in his blood, it should not have been unexpected. His parents, Richard Fraser and Paddy Glynn, were all-round actors, singers and dancers. His mother started her career as a Bluebell girl in Las Vegas, one of a troupe renowned in Paris and the USA for their beauty and high-kick dancing. His father became the black sheep of the family when he opted for acting; his own father was an RAF wing commander.

In 1961 the couple were touring the UK in a version of the 1950s musical, Salad Days, when Paddy became pregnant and was prescribed thalidomide for morning sickness. Fraser was born the following January with phocomelia (literally, ‘seal limb’). He was one of about 460 babies born with limb damage in the UK between 1958 and 1962, when the drug was withdrawn. His mother thought he had died, so when she heard he had short arms, she said with relief, ‘Oh, is that all?’ As he grew up, she did her best to protect him by trading stare for stare. His disability was not discussed. Anything Fraser wanted to do, he was encouraged to, though when his impairment allowed him to beat the other children at collecting ‘a penny for the Guy’, he had to be retrieved. The Frasers were not among the parents who waged a historic campaign for adequate compensation, though they did attend at least one meeting.

To begin with, Fraser was not worried that he looked different from other people. He could not tie his shoelaces or do up his top button, but he learned to cope with routines, like going to the loo or using a pencil. Everyday objects, such as a drawer knob, could help him lever clothes on or off. At his posh primary school, Sheen Mount, near Richmond Park, he played football like the other boys, shone at English and History, took part in school plays and enjoyed singing. People were ready to help him, especially girls. He had his own group of friends, who never mentioned his disability; only once did a boy allude to his ‘screwed-up arms’. ‘I was as much as one can be, as the only disabled kid, a regular member of the school.’

Aged about seven, he had an assessment for compensation. He remembers going into a strange room without his mother and seeing three men behind a desk. They asked him to retrieve a bag of sweets from the top drawer of a three-drawer filing cabinet. He dragged his chair to the cabinet, climbed up, took out the sweets, and dragged the chair back. When he found out it had been an assessment, he was angry with his mother for not telling him; even then, he says, he could have made it look a lot worse. He received a lump sum of £15,000, and an annual payment of about £4000 that today has risen to £12,000 (though not price index linked). The lump sum went into a trust to accrue until he reached 21. Fraser has never been eligible for Income Support (IS) because of that lump sum. He finds this unfair: compensation money is designed to reimburse you for a specific loss, so it should not be counted in an assessment for IS.

Seeing a cine film of a birthday party when he was about eight brought home to him his difference; he was shocked at his short, flapping arms. Then, a year later, his father came out as gay and went off to live with ‘Gerry’, a dancer, in Colchester. Fraser remembers six months of turmoil before he and his mother left for Auckland, New Zealand, where they stayed for 18 months. He went to the Kowhai Intermediate School, for children aged 10 to 12, which seems to have given him some welcome stability.

Back in England, Fraser and his mother settled in Canterbury, where Paddy worked at the Marlowe Theatre. Fraser’s education had taken a nose dive, academically, in Auckland; while he could weld metal and make dovetail joints, he had no idea of long division. So he was sent to Kent College, then a direct grant school.

Money was short, so Fraser’s school uniform came from the second-hand uniform shop. But that was of little consequence compared to being a day boy in a school where the boarders reigned. He became not just ‘a weed’, but a disabled weed; somebody who could be mocked for being different. For the first time, he was called ‘flid’ and ‘spastic’. He did his best to join the pack. He won over one tormentor by helping him with his maths. He found he could earn respect by entertaining the class, so he became the comedian, the one who dared to cheek the teacher. It made him both a rebel and a conformist. He was obeying his father’s admonition to ‘Be a social chameleon. When you are with Dave the builder, be like Dave the builder.’ Good advice for an actor, maybe, but dangerous for a small boy trying to be true to himself. Fraser accepted it on both levels. For him, the actor should be able to absorb any kind of character.

A highlight of Kent College was the day he made a favourite English teacher laugh. He was 13 at the time. The class had to write a little play about narration and miming and Fraser allowed one of his characters to exclaim, ‘fuck with the form’. The teacher bellowed with laughter. ‘That must have been the first moment I got pleasure from someone liking what I had written,’ he says. His ability to shock could win approval from the teacher as well as the class. Shortly afterwards, the teacher disappeared, perhaps, thinks Fraser, because he had a mental breakdown. Fraser missed him.

Two years later, he found himself in a very different environment, a comprehensive school at Tregaron in rural Wales. His mother remarried and they moved to the village of Bronnant, near Aberystwyth.

Fraser acted bravely on his first day at the new school. A huge boy challenged him to a wrestling match in front of a group in the playing field. He accepted, and was thoroughly beaten. Afterwards the boy said, ‘He’s all right, that guy; he had a go.’ There was no more bullying.

Another English pupil, Dan Jones, was assigned to look after Fraser. He had never seen anyone with a physical disability before. ‘I was very shocked. It took me a week before I could look at him comfortably.’ But then Fraser burnt a Bible, and Jones thought that was cool.

Both outsiders in a Welsh school at a time of militant Welsh nationalism, the teenagers were drawn to each other. Music cemented the relationship. While the other pupils liked Elvis Presley and the rock band Status Quo, Fraser and Jones discovered punk and made it their own. They wore the clothes, spiked their hair, swore and spat, and most of all they copied the music. Fraser taught himself drumming, while Jones played the guitar. Fraser led the way in mischief-making. On one occasion he suggested they should go to the village youth club in their punk gear and play a record of the national anthem. The result was spectacular. The Welsh kids chased them out of the club and threw stones at them. Jones still laughs at the memory of Fraser trying to run away in his mother’s high-heeled boots.

Punk was a stroke of luck for Fraser. It confirmed him as a rebel and gave him an alternative label. He and Jones were the only punks in Dafydd, he says, and attracted a lot of attention. ‘I convinced myself they were staring at me because I had spiky hair, because I was a punk. Being a punk meant I could not call myself disabled; it meant I could call myself something else.’

Difference gave him a sense of power; it even allowed him to transfer the pain, sometimes quite sadistically. One day, when a group of kids were waiting in the sports pavilion to play cricket, Fraser asked who would like to have his sunglasses. Jones recalls: ‘The Welsh pupils said, “I’ll have them, I’ll have them.”’ So Mat took them off, put them on the ground and just smashed them to pieces.’ On another occasion Fraser took his short-legged dog, Brutus, into a stream and told him to sit in the cold water. Jones still remembers the dog’s imploring eyes.

Jones eventually walked out of school before the end of the year. Fraser stayed, but failed his O levels. He spent the summer holidays in his room, listening to music and reading girly mags. Determined he should get some qualifications and discipline, his mother sent him back to Kent College, as a boarder, to retake the O level year. He says he bullied the younger people in the form, joined the ‘cool’ set, who smoked marijuana, and played in the punkier of the two school bands. A new headmaster, a former social worker, introduced a more liberal regime and the pupils were allowed to organise a rock concert at the end of the year. The girls played their part, screaming at the front, and the boys played theirs helped by cans of lager. Fraser loved being on stage and performing. ‘I was totally hooked. I knew that’s what I wanted to be, from that moment.’

But, for the time being, armed with five O levels, he went off to further education college in Colchester, where he lived with his father. Somehow or other he achieved an A level in Sociology after two years, but all that came way behind gigs, alcohol, drugs and girls. The alternative label was becoming the alternative lifestyle.

Many years later, when Fraser was starring as someone with his own disability in The Flid Show, an off-Broadway play, he remarked on the nude love scene: ‘It’s the first time you see this character actually his real self, without all the brick walls on him. That’s one of the things we are not allowed to be traditionally – sexual.’ From his teens on, Fraser threw himself into proving he was a full-blooded, heterosexual male, drowning out the knowledge that his impairment could repel some women. As a 13-year-old on a mass date, he had seen its impact on ‘the very nervous, polite and acutely embarrassed Vicky. Her look of determination overcoming revulsion convinced me something was wrong.’ He was one of the first people in the class to lose his virginity. Sexual experience with disabled girls was available on the foreign holidays organised for teenagers by the Thalidomide Society, but that led to no relationships; having a disabled girlfriend would have underlined his own disability.

Through punk he found non-disabled girls willing to flout convention, ‘though always in a private, darkened room’. He looks back on them as revolutionaries. ‘I had sussed out that only girls who could reject the confinements of society’s values would reject the negatives of disability and find the person inside.’ As his musical career developed, the rock star phenomenon kicked in, giving Fraser sexual opportunities he could exploit, a way to relieve the anger and frustration of being different. ‘He fucked it out of his system,’ says Julie McNamara, friend and colleague on the disability arts scene.

In his second year at Colchester, Fraser joined up again with Dan Jones, who had enrolled at the art college. They formed their first band, A Fear of Sex, composed of a drummer and two guitarists, with Jones doubling as singer. There was no bass player, which they thought was radical. ‘For the first time we were playing our own songs and doing our own thing,’ says Fraser. ‘It was an extraordinarily rich time in Colchester – everyone was in a band – there was so much going on.’

He wanted to move out of his father’s house and, luckily, he could draw on the lump sum compensation: £12,500 went into buying a house for him in Colchester, at 66 South Street.

Fraser was happy. He never talked about his disability, so no one mentioned it.

A Fear of Sex morphed into another band, North, which included two people on bass and keyboard, and a singer – a pretty girl, who caught the eye of the rock reviewer on the Colchester Gazette, ensuring they became the biggest band in town. Fraser had his own methods of publicity. Jones was walking along a main road in Colchester one day, when he saw what had been an empty billboard now advertising North in enormous purple letters. He followed a trail of purple paint, which led to a paint-covered broom standing outside 66 South Street.

Eventually, Jones moved to London with the rock band Living in Texas, while Fraser joined The Reasonable Strollers. Here he found serious musicians experimenting with complicated rhythms, which for a drummer used to 4/4 time were challenging and exciting. But his taste was always one step ahead; now he was into post-punk and the band Theatre of Hate, and he was outgrowing Colchester. When Jones phoned to say his band was doing a gig and needed a drummer, Fraser filled in, and stayed. Pleased to be working with his greatest friend in a band that he thought was going to ‘happen’, Fraser moved to London in 1983, to the first of many squats. His drumming won widespread respect. ‘It was very good, very inventive,’ says Jones. ‘The rhythm section was strictly Mat.’

Over the next eight years, the band toured all o...